In the seventeenth century, Huguenot Jean Claude wrote a long essay in French on how to compose a sermon. In the eighteenth century, English Baptist Robert Robinson of Cambridge translated it and annotated it. In the nineteenth century, Charles Simeon, also of Cambridge, republished Robinson’s translation of Claude’s essay and commended it to a wider audience, publishing it several times and putting its lessons into practice in his own influential publications on preaching.

That’s the short story, just indicating the key names in one trans-denominational Protestant tradition of preaching. But there are a number of interesting details to this story. In particular, what deserves further study is the way this lineage carries the notion that preaching is a thing that can be taught. In the hands of Claude, Robinson, and Simeon, this book was a tool for getting homiletics training to church leaders.

I do not know when Jean Claude (1619-1687) wrote the Essay on the Composition of a Sermon. It was not published until just after his death, when his son brought out a 1688 edition of some of pastor Claude’s works. The Essay runs from pages 163 to 492 in volume 1 of this posthumous edition, so while it was not a stand-alone book in its first appearance, it was certainly book-length.

I do not know when Jean Claude (1619-1687) wrote the Essay on the Composition of a Sermon. It was not published until just after his death, when his son brought out a 1688 edition of some of pastor Claude’s works. The Essay runs from pages 163 to 492 in volume 1 of this posthumous edition, so while it was not a stand-alone book in its first appearance, it was certainly book-length.

Claude was famous as a defender of the Reformation in France, an opponent of Roman Catholic bishop Bossuet in a series of publications, and a friend of Reformed theologians like Francis Turretin. Of the Essay, Hughes Oliphant Old says, “it is a presentation of the Protestant plain style of preaching.… Seen against its environment the essay might be called an apology for the simple approach of biblical exposition which normally took place in the worship services of French Protestantism.” Reading around in Claude’s Essay, it’s clear that he is concerned to teach preachers how to stick to a main idea and avoid distracting the audience with showiness.

Claude’s Essay seems fairly well hidden away in the second half of the first volume of a five-volume set of his posthumous works. I do not know if it had any influence in France or in French. But in 1778 it was translated into English by the Baptist pastor Robert Robinson (1735-1790), most remembered today for writing the hymn “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing.” Robinson’s most important pastorate was at St. Andrews Street Baptist Church in Cambridge, just south of the city centre.

Claude’s Essay seems fairly well hidden away in the second half of the first volume of a five-volume set of his posthumous works. I do not know if it had any influence in France or in French. But in 1778 it was translated into English by the Baptist pastor Robert Robinson (1735-1790), most remembered today for writing the hymn “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing.” Robinson’s most important pastorate was at St. Andrews Street Baptist Church in Cambridge, just south of the city centre.

Robinson was especially drawn to the Essay because he thought it would serve as a one-volume education in preaching for the Baptist ministers of his time, who were excluded from the best educations by their status as dissenters from the Church of England. In an opening “Advertisement” (what we would call a Preface) for his translation, he wrote, “The following essay is published in its present form for the use of those studious ministers in our protestant dissenting churches, who have not enjoyed the advantage of a regular academical education.” (i)

In fact, Robinson’s personality begins to peek through the project as he describes the disadvantages that Baptists labored under in the eighteenth century. He is upset that dissenters have the reputation of being ignorant and schismatic, while the Church of England preachers are supposed to be so urbane. Quite the contrary, asserts Robinson: Among the dissenting pastors, “we have not a brother so ignorant and so impudent as to dare to preach to seven old women in a hogstye, what Doctors and Bishops have preached before universities and kings.” (v) There are a lot of notes like this scattered throughout Robinson’s translation of the Essay. He says, “I have indulged a freedom of inquiry all through the following notes,” by which he means he has included examples of good (mostly Baptist) and bad (mostly Church of England) sermonizing in the footnotes throughout.

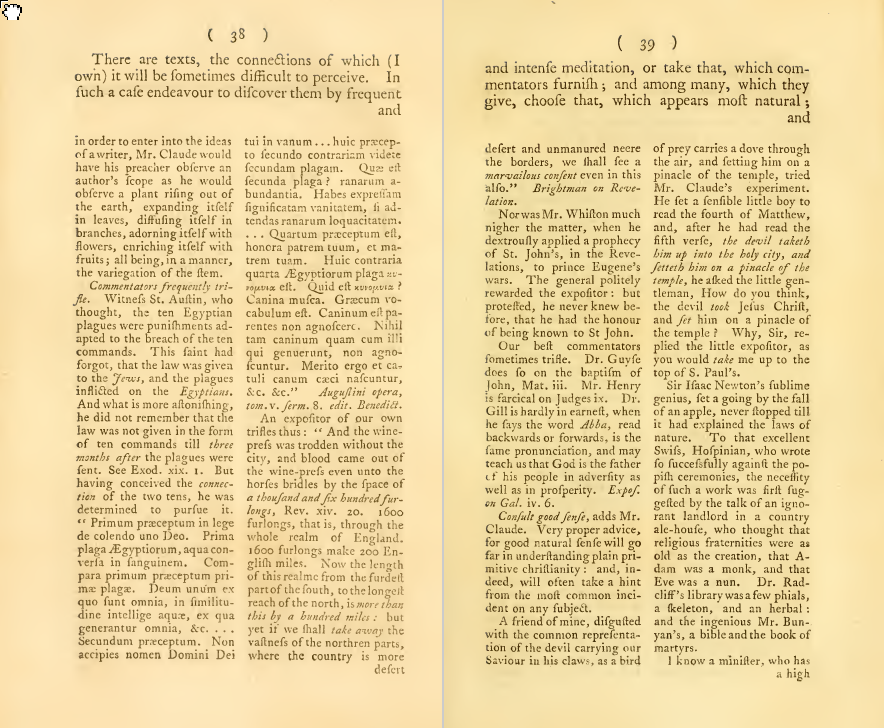

Ah, the footnotes. Robinson took Claude’s Essay and fortified it with so many annotations that it had to be published in two volumes. The footnotes, in fact, run to four times the length of the original text, according to Simeon’s count (about which, see below). Here is a two-page spread of an especially annotated section:

There is, to say the least, a whole other book going on down there. And it’s an uneven book: Robinson is well-read and quick-witted, so following any of his digressions –yes, there are digressions inside the footnotes– can lead to some wonderful serendipities and discoveries. He was the translator of a number of Huguenot sermons, so his mind is adequately stocked with information that is immediately relevant to explaining Claude’s way of thinking. He also has at his fingertips a great deal of classical learning, and can expatiate helpfully on how sermons differ from the canons of classical rhetoric. Besides all this equipment, Robinson has a lot of wisdom of his own to share along the way, especially as he speaks directly to dissenting ministers and assumes the role of an educated clergyman sharing valuable knowledge.

But he also lacks an editor to make up for his tendency to indulge in controversies. He simply can’t resist taking swipes at the Church of England. This is one of the least attractive features of Robinson’s volumes even for readers who agree with him doctrinally. Like so many writers, he’s at his worst when he thinks he’s at his best: being funny.

Robinson shows that he is aware of what an odd set of notes he has assembled. In the introduction to the volumes, he tells the story of their origin:

“Twelve years ago [that is, 1766] I first met with this essay, and I immediately translated it for my own edification, adding a few critical notes from various authors.” (vi) Then in 1772 he added more quotations to his notes, and in 1775 he was encouraged to enlarge the notes even more and to publish them. Finally, he relates, in May of 1776 he sprained his ankle and was couch-ridden long enough to carry the work out to completeness. Robinson gives this account of the book’s genesis and publication because he admits he is offering the public “a collection of notes, which must seem an odd farrago” unless you bear in mind “the different views of the compiler at different times.” (vii) Robinson signs this introduction R.R., writing from Chesterton in 1778 –and I, dear reader, if you will permit me to overshare in a Robinsonian manner, am blogging unto thee from Chesterton at this very moment.

Ignoring the unignorable notes for a moment, Robinson improved Claude’s Essay in important ways. First, he added a sixty-page biography of Claude, which helps introduce the author. Second, he introduced a number of devices into the text that greatly improve its readability: paragraph breaks, italicizing of key words, clear numbering of subpoints, and so on. All of these are palpable improvements over the Essay as published in Claude’s Posthumous Works. Third, Robinson omitted a few pages that were repetitive, especially when (as with p. 24 of the translation) the material belonged elsewhere and was actually repeated there in due course. Finally, Robinson made some major changes like moving Claude’s entire section on “le choix dex Textes” from chapter three up to chapter one: it seemed to Robinson that Claude’s sage advice on choosing a text was logically prior to anything else he had to say about “la tractation” of that text. And so, without noting these changes in his introductory matter or his notes, Robinson improved the readability of Claude’s essay as he rendered into flowing, idiomatic English.

It was Robinson’s Claude that caught the eye of Charles Simeon (1759-1836), who recommended it repeatedly during his decades-long ministry at Holy Trinity Cambridge. In 1792 he published Claude’s Essay on the Composition of a Sermon, with Alterations and Improvements. I’m looking at an 1802 second edition, though, and much later, in 1844, there appeared Claude’s Essay with Notes and Illustrations and One Hundred Sermon Skeletons by Charles Simeon, 1844. I actually find it confusing to sort out how many times Simeon published Claude, and haven’t got it all straight.

It was Robinson’s Claude that caught the eye of Charles Simeon (1759-1836), who recommended it repeatedly during his decades-long ministry at Holy Trinity Cambridge. In 1792 he published Claude’s Essay on the Composition of a Sermon, with Alterations and Improvements. I’m looking at an 1802 second edition, though, and much later, in 1844, there appeared Claude’s Essay with Notes and Illustrations and One Hundred Sermon Skeletons by Charles Simeon, 1844. I actually find it confusing to sort out how many times Simeon published Claude, and haven’t got it all straight.

But it was definitely Robinson’s Claude that Simeon published: the translation is identical in every place I’ve checked, even when Claude’s French could have been Englished much differently than Robinson’s translation. Simeon gives Robinson credit, more or less: Robinson was “a man of very considerable erudition, and who presided over a dissenting congregation in Cambridge.” The translator, however, “are, at least, four times as large as the original work,” and “are not altogether so unexceptionable as might be wished.”

The main thing Simeon objects to is the partisan character of Robinson’s notes: “Any person who reads a single page of them must see” that “they were compiled for dissenting ministers.” Furthermore, “they are replete with levity, and teeming with acrimony against the established Church.” For this reason, wrote Simeon from his position securely within the establishment of the Church of England, the time had come

to publish this Essay without the incumbrances with which the translator had loaded it. There can be little doubt but that the notes have prevented many from perusing it, who might otherwise have been much profited by its contents: and it is hoped, that, now it is sent forth in its native dress, and may be read without exciting either bigotry or disgust, it will become an object of more general attention.

And indeed it has become the object of general attention. Though Claude’s Essay is not exactly a household word, it has been highly influential, primarily through its influence on Simeon, in teaching preachers to preach. It is, it seems to me, an important witness to a particular Protestant tradition of bringing the word of God to the people of God. This blog post obviously avoids going into the actual content of the Essay; here I was only concerned to trace its interesting path through the history of preaching.