Algernon Crapsey worshiped telegraph poles, but that’s both better and worse than it sounds.

It was April 18 in the year 1906 that Reverend Algernon Sidney Crapsey (1847-1927) was put on trial by the Episcopal Church in the state of New York for teaching, preaching and writing contrary to the Christian faith. He was found guilty, and was removed from the ministry.

In his autobiography, Crapsey called himself The Last of the Heretics. In claiming ultimacy for his heresy, Crapsey did not mean that no teachers after him would deviate from the truth. Instead, he meant that since this was the twentieth century, holdovers like heresy trials were surely things of the past. He was a casualty of a medieval atavism, the last modern man to be taken down by the grand inquisitor from the dark ages.

Crapsey wrote his autobiography about twenty years (1924) after the trial, and although it is an attempt at self-justification, it provides ample evidence that he should not have been teaching or preaching in a Christian church by 1906. He claims, “I was condemned primarily not for theological, but for social, political, and economic heresy,” yet he goes on to chronicle his education as a progressive rejection of the central doctrines of Christian theology. Throughout the book, he wants it all ways at once: He wants to bear the label “heretic” with a martyr’s pride while simultaneously claiming there is no such thing as heresy; he wants to reject Christian truth claims in favor of pantheistic humanism, he wants to say he was forced out of the church for nontheological reasons, and he wants to say he had the right to continue teaching his philosophy as a Christian minister. It never seemed to occur to him that he should voluntarily step down.

Crapsey chronicles several important stages in his rejection of Christianity. One comes during meditation on a pilgrimage made during Holy Week:

As I came to the middle period of life, this system of worship began to pall upon me. Good Friday came but the emotions of Good Friday did not come with it. I did not know why, but my heart was cold to the sufferings and the death of Jesus. I had ceased to believe, without knowing it, that these sufferings and death had any relation to my daily life. I could no longer think that Jesus by His agony in the Garden and His death on the Cross had appeased for me the wrath of God. That wrathful God no longer had a place in my thoughts.

Jesus was one among many sufferers; why set aside a weekend to focus on his pain? “While I was indulging myself in the luxury of grief over One who had died more than two thousand years ago, I was callous to the sufferings and the dyings which were going on all around me.” There is a note of real human sympathy in Crapsey, but it is drowned out by his sheer, roaring incomprehension of the main ideas of the Bible.

Another key scene in his loss of faith comes when he is interrupted while giving a lecture on theology. A supervising professor tells him that his way of presenting Christian doctrine makes it clear that he is a rationalist who does not know how to handle divine revelation or church tradition. “You are worse than a Ritschlian!” the professor shouts. Crapsey is offended, though he does not know what the term means. When he looks up Ritschl in the encyclopedia, he recognizes that he is, in fact, a Ritschlian or worse, and is glad to have learned a label for this thing he is devising by following his own lights.

Crapsey’s autobiography contains some touching observations about the plight of the poor and the failure of the established political and religious institutions to help them. But these are interleaved with repeated swipes at Christian truth claims and outright mockery of the Bible and doctrine. In a later book (The Ways of the Gods), Crapsey says of Jesus, “By reason of his exaltation to the rank of an Absolute God, Jesus ben Joseph lost his human and acquired a divine personality.”

And on that little matter of the Trinity, Crapsey rejects it, rehearsing instead the Fichtean argument against absolute personality (circa 1799):

When theology came to apply the term persona to the Absolute, it was guilty of an incurable ocntradiction; one might as well speak of a square circle. Personality is limitation and a limited Absolute is just no Absolute at all. In spite of its twisting and turning, the Christian theology when it gave divine personality to Christ was polytheistic to the core. Its Trinity, in spite of all its shrieking, is three gods and never one…

With pity for the misunderstood prophet of Galilee, Crapsey laments, “Poor Jesus ben Joseph, in all that thou hast gained in divine substance and personality, thou hast lost the more in human interest and devotion.”

At the inevitable heresy trial, which Crapsey considers a major world-historical event but admits to sleeping through sections of, the prosecution presses numerous theological arguments. Crapsey’s defense counsel responds with nuance, making many distinctions and explaining how Crapsey’s views could be considered Christian, depending on what the meaning of “Christian” is. Even Jesus could be described as divine, if “divinity” is described expansively enough and guarded from misinterpretation.

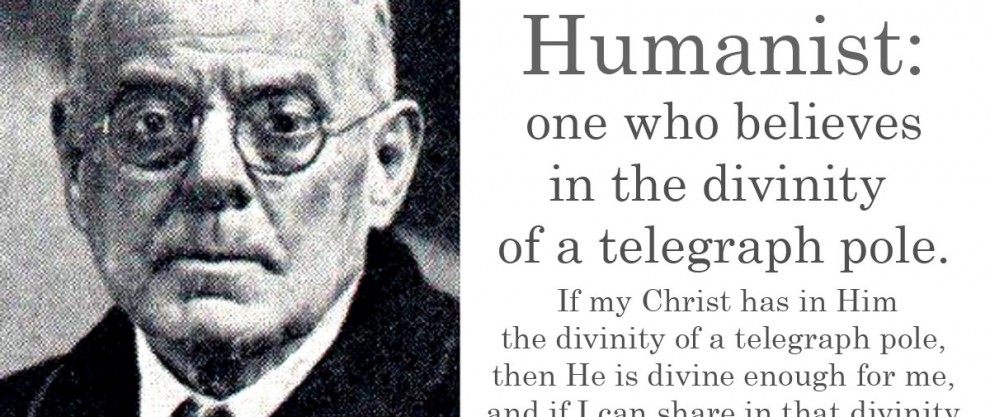

Crapsey himself identifies the key moment in the trial. One of the examiners, John Mills Gilbert, looks out the window, points, and says, “There is no more divinity in Crapsey’s Christ than there is in that telegraph pole.”

In later years, Crapsey comes to see that Gilbert was right, and in The Last of the Heretics he says “I have a religion and if asked to give it a name I should say I am a Pantheistic Humanist.” Pressed for clarity on what “pantheistic humanism” means to Crapsey, he elaborates: “I should say one who believes in the divinity of a telegraph pole. I am indebted for this definition of my religious belief to the Reverend John Mills Gilbert…”

Crapsey takes up a meditation on the objects of his veneration:

Ever after that as I walked along the highways I used to study the telegraph poles; their gaunt, naked, weather-stained forms haunted my soul. What were they? Whence came they? What were they doing? As I looked at them I saw that they were the trunks of trees stripped of their branches; they were weather-scarred and there was no beauty in them that we should desire them; lifting their nakedness toward the sky, they were a blemish on the landscape…Nothing divine there, only hopeless desolation and endless death.

What is a telegraph pole? It is this tree of the forest, cut from its roots, stripped of its branches, planted firmly in the ground, with outstretched arms nailed to its trunk, and on these arms are placed the wires that carry messages of joy and sorrow, of gain and loss, from man to man all round the world.

After a further excursus on the life-cycle of trees, Crapsey makes the application to Christ:

When I thought on these things I said if my Christ has in Him the divinity of a telegraph pole, then He is divine enough for me, and if I can share in that divinity I am content. Is not the telegraph pole the aptest symbol of my Master? Did He not begin as a human seed, invisible to the eye of man? Did not that seed bury itself deep in the substance of humanity? Did it not by its own inherent strength break out from its hiding-place into the light and air of the earth? Did it not take of that light and air and change it into the flesh and blood and wisdom of a man? did not that man become a man among men, with His relationships of son and brother, of friend and enemy? Did He not go out among His fellows speaking to them words of wisdom and comforting them in their sorrows? And when He was in the prime and glory of His manhood, was He not cut down by the ax of hate, stripped down to His nakedness and made, as it were, into a telegraph pole with outstretched arms to send His messages of warning and encouragement, of love and peace, all around the world? And to this day is not the Cross the symbol of salvation to mankind?

This meditation on the divinity in telegraph poles is not intended as a joke. Crapsey is trying to embrace the stigma of his accusers, and execute a witty Chestertonian inversion of the charges against him. And this is the rhetorical high point with which Algernon Crapsey chooses to end his autobiography, except for one final comment. As his life nears its close, he ponders the afterlife, and appends a short poem about what he expects to find. He does not want to go to heaven for any rewards or for communion with some God there. But if there’s work for him to do, and he is needed there, then he’s willing to go and help:

Is there a God, out yonder,

Sore troubled and beset;

In waters doth He flounder,

Is He faint, cold and wet?Doth He cry to me for aid

Across the seas of doubt;

Must I Death’s waters wade,

That I may help Him out?