After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands, and crying out with a loud voice,“Salvation belongs to our God who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb!” (Rev. 7:9-10)

At Wheaton College, I was part of a worship and missions group that took its bearings from this doxological, omni-ethnic vision. All of history is headed towards worship of God and the Lamb sung by people from every tongue, tribe, and nation.

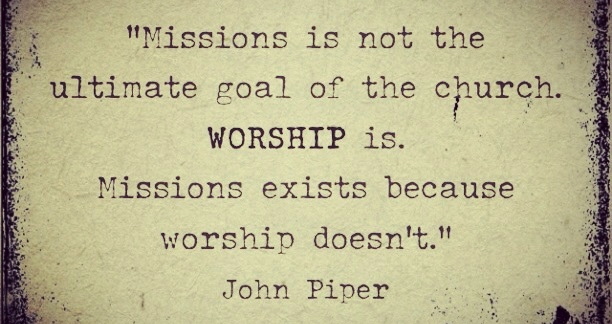

John Piper made the missional connection in the opening words of Let the Nations Be Glad!, words as theologically compelling as they are inspiring:

Missions is not the ultimate goal of the church. Worship is. Missions exists because worship doesn’t. Worship is ultimate, not missions, because God is ultimate, not man. When this age is over, and the countless millions of the redeemed fall on their faces before the throne of God, missions will be no more. It is a temporary necessity. But worship abides forever.

Worship, therefore, is the fuel and goal of missions.

Yet, despite a twentieth-century in which the Spirit’s work in the mission of the church issued in the greatest expansion of the people of God since the first century, American Christians have remained relatively isolated from the reality of global Christianity. Geography doesn’t help. Neither does the sheer size of the American economy or the reach of American culture. We can–and do–take our experience for granted as “normal,” oblivious to the fact that American Christian experience is no more universal than, say, Indonesian Christian experience. (One of the surprising benefits of American decline, then, will be our growing awareness that we are not alone in the world, that the world is not American.)

Many of us celebrate the gospel’s ability to make itself home in other cultures; we work, too, to see how very different forms of the Christian faith might nevertheless be right and good, insofar as they illuminate and embody the gospel in its new cultural homes.

But it’s only beginning to dawn on us that, as Jesus makes his home in other cultures, they might have something to teach us about this One we proclaim as Lord. An old friend reported years ago what an African Anglican bishop had called the “boomerang theory” of the gospel: “You threw it to us. Now we’re throwing it back!” Those to whom the gospel was preached turn around and preach the gospel back to those who had preached the gospel to them.

This is good news for us in Europe and America, where Christianity is frequently fatally compromised, confused, and contorted into unrecognizable shape. But even among the faithful few, the elliptical journey of the boomeranged gospel brings back an understanding of the good news of Jesus Christ that will challenge and urge us to reconsider questions that we had thought long-resolved.

Sanneh spoke of how the gospel blesses and curses every culture it meets–and also turns its finger of blessing and curse on the missionary’s culture–in Translation the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (1989). Lamin Sanneh and Andrew Walls began work here, studying the translation principle in the transmission of the gospel. Since then he has published Whose Religion is Christianity? The Gospel Beyond the West (2003) and Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity (2008). Walls’ most significant early work was The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (1996), in which he described two principles–the indigenizing principle, according to which the gospel makes its home in a culture, and the pilgrim principle, according to which it is always on the move, far from a homebody. Walls also wrote The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith (2002).

In 2002, Philip Jenkins discerned The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. Since, a number of Western Christian scholars have moved quickly beyond the mere acknowledgment of global diversity to engage in careful, extensive preliminary reports of the life and thought of God’s people in the global South. While there is no substitute for direct engagement with Christian from the global South, these scholars have sifted and sorted statistics, interviews, and difficult-to-access bibliographical sources and reported them.

Jenkins followed up his earlier book with a report on how Christians in the southern hemisphere read Scripture, The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South (2008). A few insights:

Global South Christians…do not live in an age of doubt, but must instead deal with competing claims to faith.

…one of the great strengths of the Bible in African Christianity and one of its dangers, namely that the Old Testament seems to speak so directly and familiarly to local conditions.

Jenkins suggests this can, among other thing, help rescue the global North from its constant temptation to the heresy of Marcion, in which he rejected the Old Testament.

Also striking is Jenkins’ observation that “James may be the single biblical book that best encapsulates the issues facing global South churches today,” especially “in the context of spiritual healing, of persecution and resistance, of activism and social justice, even of interfaith relations.” For American Protestants, heirs of Luther and his love for Paul and disdain for James, this is a reminder of just how much we operate with a Pauline canon-within-a-canon, to the neglect of the broader counsel of Scripture.

Mark Noll is an evangelical historian who has turned late in his career to world Christians. In The New Shape of World Christianity: How American Experience Reflects Global Faith (2009), Noll argues that America’s influence on the world is not as direct and determinative as its champions or its detractors would lead us to believe. No, the influence is more indirect; and to speak of “influence” is also to name a network of people in other cultures who actively make decisions about their appropriation, transformation, deformation, and reformation of aspects of American culture and faith. It’s better to speak of America as a “model” or “template” for later global experience. Here’s Noll in a nutshell:

The more important reality, however, is not that world Christianity is being driven by American activity. It is, rather, that forms of conversionistic and voluntaristic Christianity have flourished where something like nineteenth-century American social conditions have come to prevail–where, that is, social fluidity, personal choice, the need for innovation and a search for anchorage in the face of vanishing traditions have prevailed.

The burden of this book is to suggest that what [David] Martin describes as modern Christianity adapting to a globalizing world is similar to the process that took place in the United States when the churches of European Christendom adapted to the competitive, entrepreneurial, free-market American environment. If this parallel really has occurred, it means that American Christian experience is most important for the world not so much as a direct influence but as a template for recent Christian history.

In a companion volume written with Carolyn Nystrom, Noll tells the stories of a series of Clouds of Witnesses: Christian Voices from Africa and Asia (2011). Reading these lives, I wonder if they can’t help further the boomerang effect, as their lives become templates for contemporary American Christians. Noll and Nystrom narrate with sympathy and an eye for the intersection of gospel and culture in the lives of individual African and Asian Christians and the churches they lead, love, and sometimes leave. I was moved in particular by the life of Janani Luwum, Anglican archbishop of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Boga-Zaire during the regime of Idi Amin–who spoke the truth to Amin for years and was eventually killed by Amin’s thugs, possibly by Amin himself, one of the twentieth-century’s countless martyrs.

To conclude an already long post, let me briefly mention Thomas Oden, a scholar with impeccable credentials and a long publishing career, who has done so much to retrieve the Fathers and has now dedicated the remainder of his life to the retrieval and renewal of African Christianity, beginning with the establishment of The Center for Early African Christianity and the books How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind: Rediscovering the African Seedbed of Western Christianity (2010), The African Memory of Mark: Reassessing Early Church Tradition (2011), and Early Libyan Christianity: Uncovering a North African Tradition (2011).

And–to me a particularly exciting bridge for Western Christian intellectuals–Baker Academic’s new series “Turning South: Christian Scholars in an Age of World Christianity.” The first three titles of these, well, testimonies, are Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Journey toward Justice: Personal Encounters in the Global South (2013), Susan VanZanten’s Reading a Different Story: A Christian Scholar’s Journey from America to Africa (2014), and Noll’s From Every Tribe and Nation: A Historian’s Discovery of the Global Christian Story (forthcoming).

Tolle lege!