Henri Rossier, a nineteenth century Plymouth Brethren writer, begins his Meditations on the Book of Joshua with an arresting comparison:

Henri Rossier, a nineteenth century Plymouth Brethren writer, begins his Meditations on the Book of Joshua with an arresting comparison:

The Book of Joshua gives us, in type, the subject of the Epistle to the Ephesians. The journey across the desert had come to an end, and the children of Israel had now to cross the Jordan led by a new guide, and to take possession of the land of promise, driving out the enemies who dwelt there. It is the same for us. The heavenly places are our Canaan, into which we enter by the power of the Spirit of God, who unites us to an ascended Christ, and seats us together in Him in the glory, so that thus we enjoy anticipatively this glory which He has acquired for Himself, into which He will introduce us, and which we shall share, ere long, with Him.

I’ve written elsewhere about the prospects that Ephesians forces on the reader, and it has occurred to me that the blessings Paul describes in Ephesians seem to put the Christian on the border of a great territory of promise. When you read Ephesians, it’s only natural that you might think of yourself as following the greater Joshua into a great adventure.

Rossier makes the same observation, but goes in the other direction with it. He is writing a series of meditations on the book of Joshua, and begins by saying that Joshua is typologically presenting the spiritual truths we are already familiar with from Ephesians. For Rossier, Ephesians gives him the key to a deeper interpretation of Joshua. The struggles of Israel in the conquest of Canaan are all directly instructive for Christian readers, and Rossier’s notes on Joshua draw out passage after passage where instructive parallels abound.

In one sense, of course, this is an allegorical reading of Joshua. Allegory means, literally, talking about something else: Rossier takes up Joshua and talks about Ephesians. Reading a book allegorically is a rich and suggestive way to get into the text, but it has some notorious dangers: allegorical interpreters find a lot of neat stuff, but much of it they put there themselves. The church fathers offer plenty of examples of both the benefits and dangers of allegorical reading.

Reading Ephesians as Joshua, or Joshua as Ephesians, is an ancient trick, but the people who have made the most of it are the Christian traditions who are most eager to emphasize that there is such a thing as progress in Christian experience. There are some Puritans who specialized in teaching this way, but it was Wesleyans and then later the loose coalition of “higher life” teachers who worked it out best.

Alan Redpath, for example, kept the thread going with his 1955 book Victorious Christian Living: Studies in the Book of Joshua. “I would suggest,” he begins, “that the clue to the interpretation of this Old Testament book is found in the epistle to the Ephesians…” He goes on, “I believe that we shall understand the real significance of the book of Joshua only if we recognize that what it is in the Old Testament the epistle to the Ephesians is in the New. This suggestion, of course, has to be substantiated from the Word of God itself.”

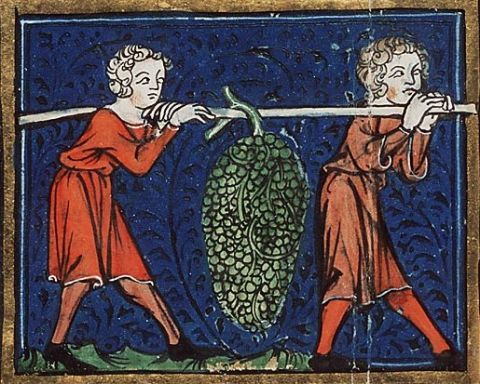

So take it as a clue and see if you can substantiate it for yourself, either reading from the Old Testament to the New, or from the New to the Old. Keep before your mind’s eye the image of God’s people on the brink of the promised land, and consider going in with the Joshua generation to possess what is yours.