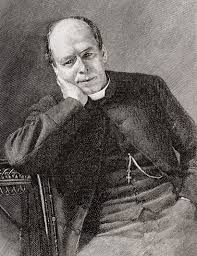

I’ve been puzzling over a perplexing passage from Henry Scott Holland (1847-1918). Holland was an English theologian who did his best theologizing in sermons, especially in the preaching he did at St. Paul’s in London, where he was a canon. The passage that I’ve been puzzling over is by turns attractive and disconcerting, both carefully formed and loosely stated, and I have not sorted out yet which elements of it will prove sound or useful (though I take a shot at doing so at the end of this post).

In his book Creed and Character (1888), Holland has a series of three sermons on “The Law of Forgiveness.” Near the climax of his cumulative argument, in the third sermon, he affirms total depravity and free divine forgiveness in eloquent terms:

“All our forgiven life dates itself from an act of God—an act originative, antecedent, fertile. God begins the work.”

And

“God must begin, if we are ever to be rescued. Here is the very key of Christian theology, and the very core of Christian faith.”

And

“we cannot begin until God has begun. To doubt this is to be ‘under the Law.'”

And

“if we are to be recovered and recalled, we must wait for a stronger Hand than ours. We have no part in it. God must anticipate our beginning… He must justify, while still we lie guilty.”

This is not some worried court theologian cautiously checking the right boxes to stay orthodox, but a preacher passionately affirming his own point and finding lots of ways to put it into words. I admit, Holland may be emphasizing the priority of the divine initiative in order to clear the field for a subsequent response from the human side, and he may be working with a latent theology of human cooperation in the response to grace (he refers briefly to “the co-operating favour of God”). This is enough to keep readers of my temperament on their toes. (And if this all turns out to be some kind of very sophisticated but finally squishy Victorian C-of-E Pelagianism I apologize for taking your time.) But this sermon begins clearly with a ringing affirmation of God’s “originative, antecedent, fertile” act of free forgiveness.

In the next section, Holland flags for his hearers the fact that he has intentionally been summoning up the Protestant theology of justification:

You recognise the language I am using. It recalls a theology which has isolated the particular truth conveyed by these terms until, in its isolation, it has become grotesque, unreal, deceptive,—yes, and morally perilous. But it is here, as in so many other cases, the isolation of the terms, not the terms themselves, which are at fault. Justification by faith, itself a paradoxical expression, which can never hold itself together against the analysis of a solvent and penetrating logic, has yet a most valid signification in that deep region where the secret of life runs back, behind logic, into paradox. It is the assertion of our absolute exclusion from the creative act by which God acquits us; in that act we have no more part or lot than in the act of our first begetting. God forgives us without our helping Him. We are justified, we are acquitted for and by nothing at all of our own, not even by our faith.

Holland treats the fact —he takes it to be a definite fact— of justification by grace alone as a kind of given, which then has to be explained somehow. And it is hard to explain because, unless it is approached in the right way, and set in the right context, it is both illogical and dangerous.

How so? Holland almost subliminally solves one problem, the problem of mistaking “faith” for some human power that accomplishes justification. That’s what he means by calling the formula “justification by faith” a paradoxical expression, and that’s why he says that we are not justified by anything “of our own… not even by our faith.”

But Holland entertains a deeper worry about justification. He worries that it is true but blankly incomprehensible. What hope, after all, can God have in the actual renewal of the people he forgives? What favor can he show to the corrupt? What love can the purity of God have for the impure? “If God has forgiven sin, then God’s repugnance has been changed into attraction,” says Holland; what is there in the forgiven that can attract God?

I take this to be the most loosely-argued movement in Holland’s thought. He is more or less dumping an intuition on his audience, or, more likely, evoking the shared intuitions that he trusts are present in his audience. At any rate, there is work to be done here in specifying and articulating the notion of lovableness that Holland operates with. Stick a pin in that; I want to hurry on to the next move, which is crucial, and which gets trinitarian.

What changes God’s attitude toward us from repugnance to attraction? “Not anything, again we say, of ours… No!” The secret remains in God’s initiative:

But the act by which God forgives, carries with it, out of Heaven, the power to work the change in us, which will justify God in forgiving. God’s forgiveness goes out from Him in such a form that it makes us, it enables us, it obliges us, to become that which we should be if we deserved to be forgiven. God the Father forgives us by anticipating that which will follow on His forgiveness.

What Holland is trying to do here is put the human response, or transformation, inside of the divine initiative somehow. Somehow, God’s “act…carries with it…the power to work the change in us.”

How? Jesus. Here’s the move, and this is what I have been trying to see to the bottom of: “God, the Father, forgives us by sending us His Son. And, in saying this, we dispose of a swarm of questions with which people besiege us.”

One of those questions is the perennial “why did Jesus have to be crucified; couldn’t the Father have just forgiven?” Holland’s position, that “the Father forgives by sending” opens the door to what must always be the right response: Jesus as we actually have him in his incarnate life is the shape the Father’s forgiveness takes. I think the accent falls, for Holland, on the sending: to put it contrastively, God does not send his Son to bring about forgiveness, but rather forgives by sending his Son. The sending is not the preliminary condition of the forgiving, but has the forgiving within it. The sent one brings it with him.

But the question Holland has been setting up for is the question about how God justifies the unjust. Here is his solution:

God’s forgiveness issues out of Heaven in the shape of Man, bearing human flesh. Jesus Christ is the Forgiveness of the Father. The Father had already forgiven the world, when he sent his Son to be born of the Virgin Mary, to be crucified under Pontius Pilate.

He arrives, bringing with him the pardon of the Father; and this pardon is effectual. For there is now in man one spot, at least, clean from defilement, on which the eyes of God’s purity can afford to rest. There is now, amid the loveless hordes of sinners, one Heart, at any rate, upon which the Father can risk the outpouring of his love; one Body, amid the hopeless and the faithless and the diseased, which can admit the rushing power of the transfiguring Spirit. The love, hope, purity of God —long homeless and unhoused— have found at last a footing within our flesh, a resting-place, a habitation, a temple.

They had looked, and there had been in man —not one that doeth good, no, not one! —not one that could respond to that appeal —not one that could surrender himself to their intimacy —no, not one; and, therefore, not one whom God could forgive.

But now there is the Son of Man in and through whom God’s forgiveness can begin to work. Christ, the Forgiveness, becomes the one forgiven Man: the one Son, who has sanctified himself to do the Father’s will.

That’s the passage. It’s really something.

Since Holland put it in sermonic idiom, I’ll try to re-describe it in theological idiom.

What Holland is doing here is opening up the sending of the Son to include not only the divine and human realities of reconciliation, but also the soteriological dynamics of the accomplishing and the application of forgiveness. He is trying to put it all into the one comprehensive thing that is the person and work of Christ. And “putting it all in Jesus” is a goal that I think a lot of different kinds of theologians can agree must be the right move. But a great deal rests on how you do that; what kind of distinctions you make; what kind of associations you establish.

Here are a few things that Holland’s move is not. I don’t think it’s the distinction between active and passive obedience, which is the conceptual tool that Reformed theologians might immediately reach for to answer Holland’s questions about what God is attracted to in the forgiven. I don’t think it’s the distinction between justification and sanctification, considered as the forensic and the organic; Holland seems to be looking for a way to avoid straightforwardly confessing the forensic character of justification proper (perhaps fearing the charge of legal fiction). I don’t think it’s what some Wesleyans have called the “high doctrine of sanctification already begun in justification,” that is, by regeneration as initial sanctification. I don’t think it’s “justification by foreseen merits,” or by a sacramental infusion of grace to do meritorious works (a Roman Catholic possibility). I also don’t think it’s Barth’s Jesus-as-electing-and-elect, though it’s perhaps closest to that in some ways (and I could also show you a footnote about how Torrance told MacKinnon to read von Balthasar, but that’s probably too rich a mix for anybody).

The reason for identifying all these things that Holland’s distinction is not, is to indicate the area in which he is moving. Somewhere in the midst of this set of issues, he is trying to establish a larger background picture which will make sure all the pieces are not held in isolation, but in their proper relations. If we are to believe him, he wants to affirm some key biblical and Protestant ideas, but to rescue them from a dangerous isolation.

What he hits on is a strong connection between the Father and the Son, which he describes in terms of sending. Holland doesn’t do much more with this, though he is the kind of writer who can suggest a lot without having to spell it out. Holland’s standard touch points (especially in this volume) are the kingdom of God and the influence of Jesus. In the rest of this sermon, he draws a practical application from the fact that our salvation is a prevenient truth at a primal level, as securely behind and beneath us as our own creation: birth and new birth are in God’s hands. It’s a strong word of assurance, tethered to the enthronement of Christ at the right hand of the Father, but (especially if you’re reading it after the intervening 131 years of theology) doesn’t quite escape the gravitational pull of a latent universalism. Holland is deep and unpredictable, so it’s worth paying close attention to what he’s actually doing.

But he’s conjuring with fundamental principles of theology, and I’m more interested in what could be done with some of his ideas than what he did with them.

Here’s what you could do. You could frame a theology of the Father-Son relation as primarily a statement about God’s own perfect life. Then you could develop a theology of the trinitarian missions, with a special focus on how the sending of the Son is God’s supremely fitting way of being present to us in revelation and redemption. The main conceptual work to be done there would be precisely the work of opening up the category of mission enough to display how the work of Christ is grounded in his eternal relation to the Father (reading back upward, so to speak, along the line of the sending) and then displaying how God makes present among us what he is in himself in the unity of Father, Son, and Spirit (reading downward, so to speak, along the line of the sending). This would make possible a clear confession that the sending of the Son is a broad enough category to justify the statement, “the Father saved by sending,” because it would include the work of Christ within itself, in a broader context. Finally, you could incorporate the human response to the trinitarian mission by attending to the eternal Son’s incarnated sonhood, and the Spirit’s application and activation of that sonhood in believers. This would be a hospitable place to locate the forensic character of forgiveness as well, ensconced within the trinitarian and incarnational architecture.

Making a place for that forensic element is what I suspect Holland had no interest in doing. He may have thought that giving absolute priority to the initiative of God’s action in salvation was an adequate way of preserving the graciousness of grace, and he may even have wanted to eliminate the forensic element of justification. If so, Holland’s soteriology, and its suggestive use of the category of sending, may be another example of theologians forced to make the most of the materials at hand after unnecessarily jettisoning other materials. Those who are not persuaded that a more traditional Protestant soteriology needs to be discarded should gratefully take advantage of such insights, and incorporate them into a more complete project.