Today (October 8 ) is the day that the Fourth Ecumenical Council, the Council of Chalcedon, began in 451. In a 2007 blog post about Chalcedon, I said

Chalcedon means classic christology. Of course Chalcedon was a city near Constantinople, but the theological meeting held there in 451 was so important and influential that for the rest of Christian history the name “Chalcedon” has been a pointer to the right doctrine about Jesus Christ in distinction from errors.

The classic words of that classic christology go classically like this:

He was begotten before the ages from the Father as regards his divinity, and in the last days the same for us and for our salvation from Mary, the virgin God-bearer, as regards his humanity; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only-begotten, acknowledged in two natures which undergo no confusion, no change, no division, no separation; at no point was the difference between the natures taken away through the union, but rather the property of both natures is preserved and comes together into a single person and a single subsistent being.

And I paraphrase, with an evangelical accent, thus:

In Christ, God and man neither merge nor diverge. In Christ, God and man are hypostatically united, and one of the Trinity dies our death on the cross, to rise again for us and our salvation. This is the way the Chalcedonian categories serve the gospel story.

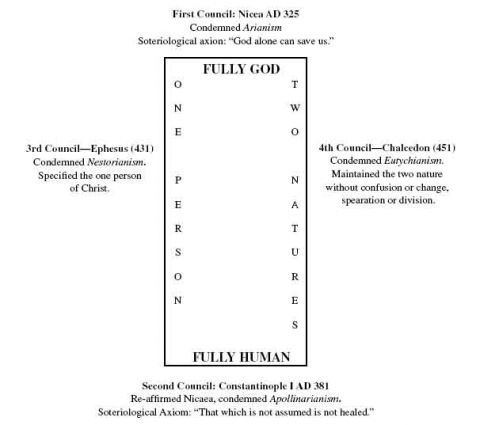

I’m co-editor of a book that warmly commends Chalcedon’s wisdom, especially as a resource for evangelical theology. That book, Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective (B&H Academic, 2007), is still available for sale, and would make a lovely Halloween, Thanksgiving or Christmas present for you or a loved one. Yes, folks, that’s Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective. Click on through and buy at least one copy today, won’t you? Act now and you’ll also receive this handy Chalcedonian Box diagram, free inside every copy of the book. It’s printed on page 24:

The chart is a visual aid I made up in teaching christology to undergraduates and in churches for a few years. It comes complete with this explanation:

Perhaps the best metaphor for what Chalcedon accomplishes is that it provides definite boundaries on four sides: On the top, it affirms Nicaea 325 (contra Arianism) by demanding that Christ is God, consubstantial with the Father. On the bottom, it affirms Constantinople I (contra Apollinarianism) by demanding that Christ is human, consubstantial with us. The soteriological axioms “God alone can save us” and “what is not assumed is not healed” mark these boundaries out. As for how the divine and human elements come together, Chalcedon marks out the right and the left with its four mighty negatives: no confusion and no change on the one hand (contra Monophysitism Eutychianism), but no division and no separation on the other hand (contra Nestorianism).