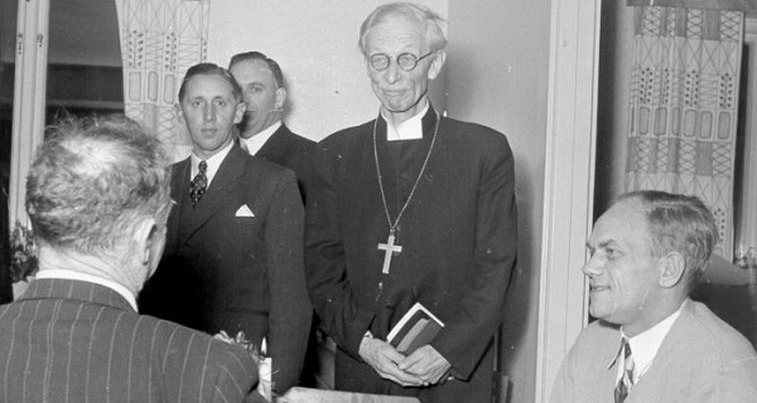

Gustaf Aulén (born this day, May 15, 1879; died 1977) was the Lutheran bishop of Strängnäs, Sweden, and the leading figure in a loosely-defined movement within twentieth-century theology called the Lundensian Theology. The other major figures in the movement were Anders Nygren, Ragnar Bring, and, at a distance, Regin Prenter. The label Lundensian, which is not a perfect fit, points back to the origin of this theological mindset in the theology faculty at the University of Lund.

Gustaf Aulén (born this day, May 15, 1879; died 1977) was the Lutheran bishop of Strängnäs, Sweden, and the leading figure in a loosely-defined movement within twentieth-century theology called the Lundensian Theology. The other major figures in the movement were Anders Nygren, Ragnar Bring, and, at a distance, Regin Prenter. The label Lundensian, which is not a perfect fit, points back to the origin of this theological mindset in the theology faculty at the University of Lund.

There are two main features of the Lundensian theology movement. First was its attempt to mediate between conservative Lutheranism as found in the Swedish state churches on the one hand, and the high liberalism of the nineteenth century, which was such an irresistible force in European academy theology, on the other hand. Second was its conviction that all God’s ways and works find their best expression in the work of Martin Luther.

The first feature threatens to position the Lundensians as compromisers, mediating between liberal and conservative, between academy and church. All self-consciously mediating theologies invite certain attendant miseries and mushinesses. But Bishop Aulén also liked a good fight, and was a good strategic thinker in what he viewed as a pitched battle against the suicide of Christian conviction in high liberalism. Even if Aulén’s work is in some ways not satisfying for evangelicals today, he struck a mighty blow against the liberalism of his time at several decisive points.

The second feature may seem sectarian, since in every Aulén book you can count on all roads leading to Luther eventually. But Aulén (and Nygren as well) thought that Luther belonged to the entire ecumenical church, and worked hard to present the riches of his Lutheran heritage as a gift to the whole Christian world.

Both features are prominent in Aulén’s most famous book, Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Atonement.

There is a trope, even a cliche, of modern theological thought which goes like this: The early church in its classic period settled the issues of Trinity and Incarnation, but made no consensual statements about Atonement, recognizing instead a variety of biblical motifs on the subject. As a result, there is no such thing as THE doctrine of the atonement, and the history of Christian doctrine has given rise to a variety of theologies of the atonement. The next step for this conventional approach is to set out a typology of different kinds of atonement theology. Aulén may not have invented this approach, but his Christus Victor is the modern classic on the subject.

By now, there are so many typologies of atonement theology that I have even seen a a meta-typology, a typology of the typologies. Perhaps this is the unavoidable way that we must approach the doctrine (though it often seems more like a failure of nerve). One thing to notice is that whoever sets out a typology of atonement theologies is already making some important decisions about what counts.

Aulén was no exception. His “three main types” of the idea of atonement are the objective type associated with Anselm (satisfaction of God’s honor), the subjective type associated with Abelard (moral influence by transcendent example), and the classic type associated with Luther (Jesus defeats the enemies of God and man). This typology is designed to push the subjective, moral influence view of the atonement out to the margin of Christian faith. That is, Aulén describes this liberal view as so incidental to the core of authentic Christianity that he marginalizes it by his description of it. That enacts the first feature of the Lundensian theology, its protest against liberalism. The second feature, in which the ecumenical Luther saves the day, is also conspicuous in the typology: What Aulén calls “the classic view” of Christus Victor is all over the Bible and the church fathers, but is classically stated and put back in its central place by the Reformer Martin Luther.

Aulén’s little book has many problems and limitations, but his approach to the doctrine has been taken as an inescapable point of reference from the time it first appeared. It is very well written and compellingly argued, so it is still worth reading even for those of us who don’t find all we need for a robustly biblical atonement theology in his typological handling of the doctrine.

Aulén also wrote a one-volume systematic theology called The Faith of the Christian Church, which is just under 500 pages and was widely used in Protestant seminaries for some time. It has Aulén’s characteristic clarity and is a stimulating work, but the methodological sections I have read seem to drift back in the direction of Schleiermacher’s liberalism a bit.

Aulén also wrote a disappointing book with the promising title The Drama and the Symbols, but I have never been able to profit much from it. In 1971, Robert Jenson started his review of the book with a classic, Jensonian book review zinger:

Aulén’s book can best be recommended as a convenient, true-to-type, and not too rigorous sample of one modern way of doing theology. It is a way of which I disapprove entirely…