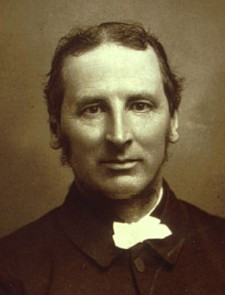

Today (December 20) is the birthday of Edwin Abbott Abbott (1838-1926), the English scholar remembered now as the author of Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. A pleasant, short, and stimulating work, Flatland is a great little mental workout that helps you imagine the jump from lower dimensions to higher.

Today (December 20) is the birthday of Edwin Abbott Abbott (1838-1926), the English scholar remembered now as the author of Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. A pleasant, short, and stimulating work, Flatland is a great little mental workout that helps you imagine the jump from lower dimensions to higher.

It’s the story of a square, living in his two-dimensional world, who travels in a dream to a land of one-dimensional points. Try as he might, he can’t convince the point-people to believe in the line-and-shape people of Flatland. Upon awaking, he is visited by a messenger from the third dimension, Spaceland. Our square hero becomes the apostle of that higher dimension, but is disbelieved and persecuted for his teachings.

C.S. Lewis caught the theological implications of Flatland, and made use of them pretty often throughout his works: To explain how angels and humans can relate in the Space Trilogy; to explain why we can’t comprehend the Trinity in Mere Christianity; and to foil reductionism (or “nothing-buttery”) in the sermon “Transposition.”

Though Flatland has a happy home in introductory math classes these days, Edwin Abbott Abbott’s main interests were actually theological. That is, C. S. Lewis put him to the right use, or Abbott’s intended use. Sort of. Both Abbott and Lewis were masterful communicators and clarifiers of doctrine. But Lewis was conservative, while Abbott was a theological liberal.

To call Edwin Abbott a liberal is not to dismiss him, nor to call him anything but what he called himself. In the 1879 introduction to a set of sermons preached at Oxford, Abbott advocated “Liberal Christianity,” and described his message as falling in between two extremes:

In every Church and in every age the Party of Growth has to contend with two other parties, the Party of Destruction, who would destroy everything, and the Conservative Party, who would preserve everything as it is; and these two Parties will always make themselves more easily intelligible than the first –the Party of Progressive Truth. To retain everyhting exactly as it is, or to destroy everything root and branch –either of these has the merit of being a plain policy, appreciable by the laziest of minds in the laziest of humours…

Abbott thought of himself as a good Anglican holding to a middle position between critical atheism and theological conservatism. But even with the alternatives that far apart, Abbott ultimately listed closer to side of “the Party of Destruction.”

He was Cambridge trained (St. John’s), with highest honors in classics, mathematics and theology (triple threat!). He loved the philosophy of Francis Bacon, and he saw an age of scientific perfection coming on. So even though the atheistic position was utterly unacceptable to him, he thought the old ways of believing were doomed:

For if Christianity is based upon miracles, and miracle after miracle melts away bneath the rays of scientific and critical discovery, there is clearly but one fate possible for the superstructure.

As a result, Abbott had only pity for those who “fear that their Christianity may be exploded to-morrow by the application to the Greek Testament of the same rules of criticism which we should apply to Thucydides or Aeschylus.” He expected that certain higher-critical theories would soon be proved “as certainly as a proposition of Euclid, and in such a manner as to prevent further controversy on the point.” Later in life he made his own contribution to pushing forward with critical views on the origins of the gospels, even causing a controversy by publishing “the assured results of modern criticism” not in theological journals, but for a general public in the Gospels entry in the Encyclopedia Brittanica.

Abbott wasn’t the worst kind of liberal, but he had the disease of accepting historical criticism quite uncritically, and if everybody had taken his advice in the late nineteenth century, there would not be any Christians around now in the twenty-first. He was deeply offended at John Henry Newman (and his Newmanianism), not because Newman was Catholic but because Newman really believed that Christian stuff, miracles and all.

Above all, what makes Abbott a liberal worth reading is that he was honest. At the turn of the twentieth century, liberals developed a terrible tendency to obfuscate, dissimulate, and deceive. But Abbott was a born teacher, and he made his views absolutely clear, pushing harder every year to make sure he was explaining precisely what the church, according this Baconian rationalist lights, ought to believe and teach. The high point of his argument can be found in The Kernel and the Husk, but Abbott sought clarity in all of his writings. This is the man who wrote a still-useful book on How to Write Clearly. This is the imagination that gave us the thought-project of Flatland. Throughout his life, Abbott even worked his progressive views into three novels of primitive Christianity (Philochristus (1878), Onesimus: Memoirs of a Disciple of Paul (1882), and Silanus the Christian (1906)),

Reading a bunch of Abbott’s theological and biblical-critical work kind of throws a shadow across Flatland. In retrospect, it’s clear that he felt like a three-dimensional Christian trying to talk to two-dimensional bigots, whether of the atheistic or conservative variety. But if you squint at that, Flatland is still a great workout, and is still useful for Christian thought: for exactly the kind of reasons C.S. Lewis pointed to.