Scottish theologian James Orr (1844–1913) was born on this day, April 11. He was a prolific author and an important figure in conservative evangelicalism at the very beginning of the twentieth century.

Scottish theologian James Orr (1844–1913) was born on this day, April 11. He was a prolific author and an important figure in conservative evangelicalism at the very beginning of the twentieth century.

Orr wrote at a time when everything seemed to be flying apart: historical-critical studies of the Bible were reaching a sort of critical mass, everything was being called into question, and the news of conservative Christianity’s imminent collapse was reported on every side. In that setting, Orr issued his voluminous series of books, articles, and reviews, in a coordinated campaign to “strengthen the things that remain.” He was the man for the job. His writings cover an astonishing range, but all of his work seems to be characterized by three concerns: Content, coherence, and continuity.

Content means that the Christian faith is about something. It’s got stuff in it; things to believe, to know, to affirm, to consent to, to experience. The overwhelming pressure of the age was pushing Christianity in the direction of a merely ethical, and thoroughly privatized, commitment. Liberalism had reached its perfect expression in the theology of Albrecht Ritschl, who trimmed it to fit Kantian limitations and defended Christian theology as a coordinated series of value judgments quite distinct from anything factual. James Orr wrote a substantial critique of Ritschlianism before most conservatives could even pronounce it. He insisted

that there is a truth, or sum of truths, involved in the biblical revelation, for which it is the duty of the Church to bear witness; that Christianity is not something utterly formless and vague, but has an ascertainable, statable content, which it is the business of the Church to find out, to declare, to defend, and ever more perfectly to seek to unfold in the connection of its parts, and in relation to advancing knowledge; that this content of truth is not something that can be manipulated into any shape men’s fancies please…

And that way of describing the faith’s content led directly to Orr’s insistence on its coherence: Christian doctrine is not a loose collection of thirty-three things having nothing to do with each other, imposed by mere outward authority. No, it is a living system of truths that all mutually imply one another, and that can be unfolded as a comprehensive, organically connected worldview. In fact, it’s largely because of Orr that conservative evangelicals talk so much about worldview to this day (even if Jamie Smith wants them to stop). Orr’s classic statement of the coherence of doctrine came in his 1893 book The Christian View of God and the World with the important extended title “as Centring in the Incarnation.” It is a robustly theological project. J. I. Packer called it “the first attempt in Britain to articulate a full-scale Christian world and life view against modernist variants.”

And the controversy with “modernist variants” brings us to his concern for continuity. Glen Scorgie’s important book-length study of Orr bears the title A Call For Continuity, because Scorgie thinks that Orr’s “contribution may best be described as a call for continuity with the central tenets of evangelical orthodoxy.” Orr had a steady vision of what the Christian faith had always been, and he was confident that it would continue to be that, long after nineteenth-century rationalism and criticism had died away. “In all his efforts he was sustained by the conviction that the rationalism of the times, which he regarded as the root cause of orthodoxy’s troubles, was a temporary malaise.” (Scorgie, p. 2).

In project after project, Orr picked subjects that he knew to be part of the great Christian heritage in need of defense in his time: he wrote solid books on the virgin birth, on the resurrection, and on the inspiration of Scripture. (The latter book, Revelation and Inspiration, is one of the liveliest and most compelling books on the doctrine of Scripture in the conservative evangelical tradition, driving with implacable logic toward the doctrine of plenary verbal inspiration before suddenly, disappointingly, pulling up short of affirming inerrancy.)

Orr was near the end of his life when Lyman and Milton Stewart funded the project of The Fundamentals, that 90-chapter resource of the best evangelical scholarship on the most important controverted areas. It shows Orr’s stature that he was tapped to write four of the chapters for the project.

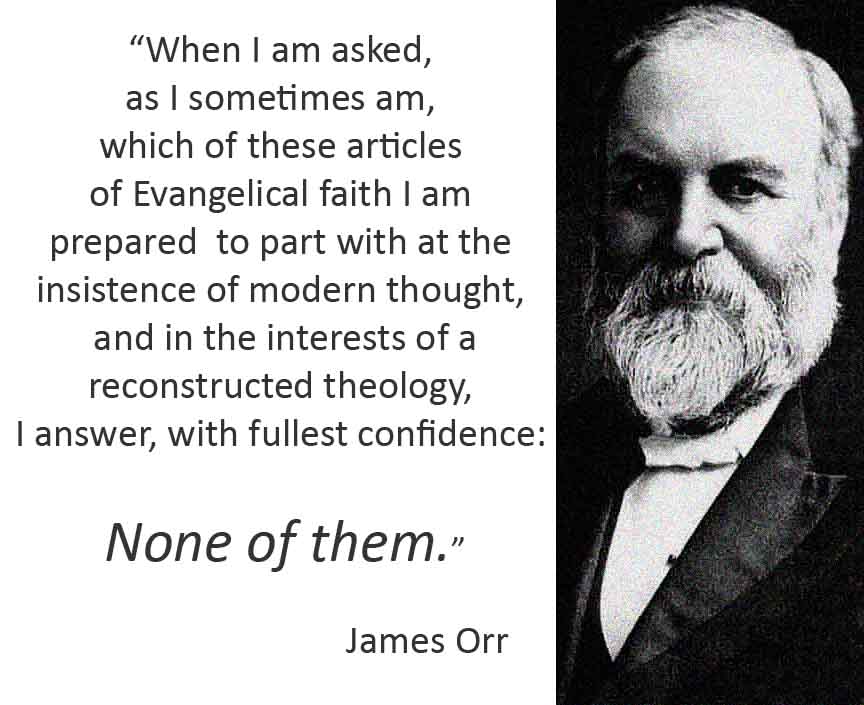

Christian doctrine has real content, it is coherent, and even when it has to fight for its existence, it is still in continuity with the great tradition. That is why late in life, Orr wrote: “When I am asked, as I sometimes am, which of these articles of Evangelical faith I am prepared to part with at the insistence of modern thought, and in the interests of a reconstructed theology, I answer, with fullest confidence: None of them.”