Here is a helpful way of thinking about the relation between the life of Jesus and the resurrection of Jesus. “His life rose with him.”

Here is a helpful way of thinking about the relation between the life of Jesus and the resurrection of Jesus. “His life rose with him.”

When Jesus rose from the dead, he not only came back to life, but also brought back with him the life that he had already lived. In addition to being now physically raised, he was also, we might say, biographically raised. His biography came to life with him and manifested its identity as the human life of a divine person.

A gospel is not just a sub-genre of biography, which happens to have the life of Jesus as its subject. A gospel is in fact a much stranger and more unique genre than that. It is the story of a resurrected person, written after the resurrection by somebody who understands the meaning of the resurrection, but largely occupied with giving a sense of what it was like to be with that person before the resurrection and with no real understanding of the coming resurrection. A gospel is a post-Easter document of a pre-Easter life. But the post-Easter understanding is baked into the telling of pre-Easter. They are written as proclamation, in order, as John explicitly says, “that you may believe.” And each gospel, in its own way, shares what it was like to make the transition from unbelief to belief: Mark with his messianic secret, John with his beautiful ironies, Luke-Acts with its Pentecostal transformation, and Matthew with his multi-layered discourses. Each one leads the reader through pre-Easter perplexity to post-Easter perspicuity.

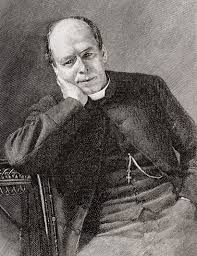

The phrase, “his life rose with him” is a rich turn of expression with many applications. It comes from a late nineteenth-century sermon by Henry Scott Holland (H.S. Holland, “Criticism and the Resurrection,” in On Behalf of Belief: Sermons Preached in St. Paul’s Cathedral (London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1892), 1-24). I have seen it quoted by Donald MacKinnon and others; most recently it appeared in the title of Gerald O’Collins’ article,, “‘His Life Rose With Him’ —John 21 and the Resurrection of Jesus” (Irish Theological Quarterly 2019, Vol. 84(2) 1–17). O’Collins’ article offers a re-reading of the first 20 chapters of John in light of all the echoes and allusions packed into the single chapter of John 21. I, too, find the phrase initially most helpful in drawing out the deep, theological substructure of the gospels’ basic form.

Holland’s own preoccupations around 1892 had more to do with historical criticism of the Bible and Christian origins: he was concerned to preach to his urbane hearers the certainty of the Christian creed in a time when the rising tide of critical studies seemed to be taking the ground out from under the feet of believers Recall “Dover Beach” and all that deeply felt dry-rot: Matthew Arnold’s poem with that title was from 1867. Germany had the death of God, but England seemed to settle for scheduling an extended divine convalescence that gradually turned instead into theological hospice care. Holland was alert to all of these trends, and his preaching on the resurrection stood decisively against them: this sermon is on the text “If Christ is not raised, your faith is in vain.” And he means it:

any criticism which supposes that this belief can be treated as surplus age, as a merely decorative accident, as the mythical expression of enthusiasm, as comparable to the apotheosis of a great heroic figure … has missed the point which it undertakes to explain. It has slipped off the scientific track ; it has ruled itself out of court.

Christianity is not just a frame of mind or a worldview or an attitude, but depends on a historic intervention of God into history in the person of Christ. Holland was in some ways a liberal theologian. He seems to have taken for granted that Christians would need to change a lot of their beliefs in order to accommodate the latest findings of critical scholarship. Holland himself would contribute a chapter in 1889 to Lux Mundi, the collection of essays that was initially notorious precisely for its editor’s low view of biblical inspiration and a general willingness to concede far too much to destructive criticism. But what he sought to emphasize, amid all sorts of concessions and reformulations, was what had to stay the same: the things articulated in the Apostles’ Creed, for instance, and the living presence of Jesus Christ himself, alive again and working among us after his own death.

It was probably intellectual and spiritual tensions of this sort which drove Holland to formulate the sermonic argument that “his life rose with him.” But it is a principle that I think throws great light on the gospels and on the mission of Jesus.

Holland opens his sermon with the voice of Paul, writing in that very early period before our written gospels were circulating, urging the Corinthians to remember the resurrection of Christ, without which their faith is vain:

Paul takes his hearers back to the very ground of all belief, to the first premise of all discussion, to the core and heart of the Creed, the Resurrection of Christ. Here, at any rate, he argues, is no idea, but a fact ; no spiritual ideal, but an actual event. And just by the force of this, its concrete, solid, matter-of-fact actuality, it determined the question of their own resurrection in a sense directly contrary to that of the idealists

For Paul and for Holland, “belief in the Resurrection is the root of Christianity. Everything runs back to it ; everything flows from it.”

Holland’s key opening move is to consider the life of Jesus in itself as a series of events leading to his death; a death which appeared to be a defeat, a burial which seemed to be the entombment of any plans this putative Messiah may have had, an end of a life that was admirable and beautiful in itself but which set in motion no lasting forces. What Holland wants us to call to mind is

the absolute insufficiency of our Lord’s earthly Life and Mission to give the momentum which originates a new religion. Nothing had been done at all, antecedent to the bitter end on Calvary, which can the least account for the after-consequences. Nothing stable had been rooted and established; nothing had taken more than the most tentative shape… Much had been dimly hinted ; much seemed about to be happening. There was great talk of a kingdom that should come, of a Church that should be built.

This is not the same thing as saying that Jesus was a failure or a loser. It’s not that he tried to do something but was unable to do so. Instead, he seemed somehow to be actively and directly involved in keeping his own programs from mounting up to fulfillment. “He fled; He hid; He scattered them. He set Himself to bewilder, to baffle, to disappoint them. Nothing came of it all, but a sense of splendid promise that yet never took shape or substance.”

Of course all of this is how the life and work of Jesus “would have looked if nothing had ever followed; how terribly short and swift its passage; how miserably small and unstable its actual achievement!”

The life, minus the resurrection, simply stops. But

It is the Resurrection which alone gave constructive force to the Life that lay behind it. A vision of unutterable beauty, indeed, that Life would ever have been; but a vision that came and passed and vanished before men’s bewildered eyes had had time to secure it, or their hearts to apprehend what was there, for a fleeting moment, in their midst.

In the Resurrection, it was not the Lord only Who was raised from the dead. His Life on earth rose with Him; it was lifted up into its real light.

The Spirit had come upon it; and that which had been all partial and piecemeal now first cohered together and showed itself substantial, and became a living thing. Now, first, the promises gained reality, the vision became concrete, the symbolic acts obtained solid footing, the deep words lost their shadowy, intangible remoteness. A light flashed back from Easter morning, and poured daylight on what had been so dark. The events that had seemed so tangled and confusing now strung themselves together on a clear and comprehensible method. The cue was given, and all was intelligible.

In these passages, Holland seems sometimes to be talking about the narrative coherence of the life –the way the events of the story go from seeming like one thing after another and are transformed into a plot, an arc, a real story– and the actual coherence of the life –the meaningfulness that cohered in the things Jesus did, taught, and suffered. I think he is talking about both, but that the energy of his prose comes from the suggestion that the meaning of the events somehow flows back to them from the resurrection they were secretly moving toward.

Holland especially lingers on the transformation of the disciples, and above all their understanding of Jesus’ person and mission:

The men who, in the Gospels, never can win possession of the Lord’s mind, never are level with His meaning, never can follow His transitions, never can ask a question without blundering, never can get sure of them selves, never can help misunderstanding His teaching, never can get out of themselves, never can understand to what the Master is leading them, not though He take them aside and prepare them, and shut Himself up with them to school them, and reiterates again and again the deliberate purpose with which He goes to Jerusalem ; the men who were still, after all the miracles, without understanding—having ears, heard not ; the men who understood none of those things, but the ” saying was hid from them, and they perceived not the things that were said ; ” the men who could despair, as Thomas, or could forsake, as all did, or could deny, as Peter ;—these very men are found, in the first chapter of the Acts, in complete and secure possession of the Lord’s secret.

And here is where the pre-Easter and post-Easter contrast pays off in the reading of the gospels. “All the words that ever fell from the Master’s lips —words which then baffled, startled, upset, distressed them —are now to them clear and limpid as the day.”

This principle makes sense of Christian participation in Good Friday and Holy Saturday: the dying and dead Jesus is present to us not in the power of dying or death, but in the power of an indestructible life. His life rose with him, which is why we encounter his life even in the events of his death. It is the risen Jesus who makes his death the subject of proclamation at all, and certainly the subject of proclamation as good news. The fact that his own death is in the hands of the risen one, and given to us by that risen one, is why his death does not stay put only in its proper historical place, or recede further back in time as we get further along the chronological line from it.