Tertullian’s Apology is a magnificent work from around the year 197. In 50 short chapters, this legally-trained apologist from Roman North Africa lays out the case for the truth of the Christian faith, defends Christians against all sorts of bizarre urban-legendy slanders, and defies the injustice of the church’s imperial persecutors. He starts out with “just listen to us” and ends with “go ahead, kill us; it will only make us stronger.”

Tertullian is verbally playful, and even at his most earnest he cant’ help being sarcastic. Phrases like “the soul is by nature Christian” and “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church” are here, along with plentiful doses of sharp-witted argument. Tertullian’s at his best or worst when he’s cornered. “Throw the Christians to the lion!” he reports the Roman rabble as shouting, and he replies with a sneer, “All of them to one lion? Must be a pretty hungry lion.”

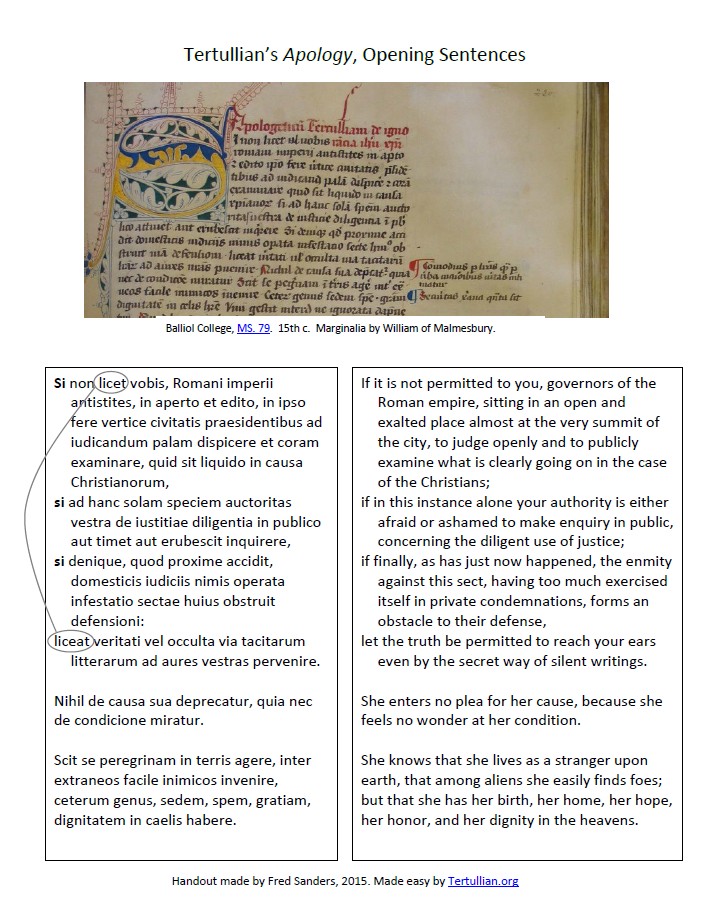

While studying the book with our Torrey students this week, I developed a bit of a crush on the opening sentence. It’s a sprawling, periodic construction that shows many signs of polish and repays close scrutiny. I compared a half-dozen translations (that sounds like real scholarship, but Roger Pearse’s Tertullian.org made it something I could do from my couch) and cobbled together this version, attempting to retain as many features of the original Latin as possible:

If it is not permitted to you, governors of the Roman empire, sitting in an open and exalted place almost at the very summit of the city, to judge openly and to publicly examine what is clearly going on in the case of the Christians; if in this instance alone your authority is either afraid or ashamed to make enquiry in public, concerning the diligent use of justice; if finally, as has just now happened, the enmity against this sect, having too much exercised itself in private condemnations, forms an obstacle to their defense, let the truth be permitted to reach your ears even by the secret way of silent writings.

The sentence progresses by three “if” clauses: If it’s not permitted, if you’re afraid, if recent private condemnations are an obstacle… These “if” clauses accumulate, bringing all sorts of color and associations with them, until they issue in an implied “then:” “Let the truth be permitted to reach your ears.”

The contrast is between open inquiry (what the Roman governors ought to engage in) and the secrecy of written communication (what Tertullian offers). A remarkable vocabulary about openness dominates the first half of the sentence: open and exalted, summit of the city, judge openly, publicly examine, what is clearly going on, enquiry in public, diligent use of justice, etc. Rather than this, Tertullian says he’ll settle for slipping them a booklet to read in private: secret, silent, written.

The root of the sentence, the simple subject and simple predicate, is “let truth.” And when that “let truth be permitted” finally shows up near the sentence’s end, it echoes the first few words: “If it is not permitted to you…” But Tertullian left those first words (si non licet) passive, never clarifying just who it is who is not permitting the Roman officials to seek the truth. High and exalted as they are, there are nevertheless, apparently, certain things that “it is not permitted” for them to do.

Tertullian never says who’s holding the other end of the leash. But he does offer these poor, pet governors a chance at freedom: Let truth be permitted. Let it sneak in, in the form of written communication, silently into the ears of your mind. If truth is too unpopular to hear about in public, sneak a peek at a forbidden book.

Let it sneak in, or rather, let her sneak in, because as Tertullian lands his sentence on truth (a word he has somehow saved up for the final clause), that word tips forward into the next sentence (a short one, nicely contrasting with the epic first sentence) and comes out personified, feminized:

She enters no plea for her cause, because she feels no wonder at her condition.

She knows that she lives as a stranger upon earth, that among aliens she easily finds foes; but that she has her birth, her home, her hope, her honor, and her dignity in the heavens.

Truth the refugee, truth the displaced person who knows better than to expect honorable treatment in this foreign land. This is Lady Wisdom of celestial origin, who cried out in the streets of Jerusalem (Proverbs 8) but is not allowed to raise her voice in Rome. She is not personally in danger, because her status is safe in the heavens. But here among us she “easily finds foes.”

Let her sneak in through this little book, pleads Tertullian. If you’re not allowed to give her a fair trial, let her sneak in.

Well, Tertullian’s opening gambit has all that and more in it. As he constructs the rhetorical situation, he sets up a tension between this present age when injustice is open, and the coming vindication, when truth will make earth her turf, her property, her domain. That dynamic holds the entire Apology together, as it moves through an exposition of the content of the Christian faith to the reality of martyrdom.

I made a handout to assist in the close reading of this sentence, with English and Latin in parallel columns and a pretty picture of a manuscript of the Apoogeticum for eye candy. For a .pdf of the handout, click on the picture of it above, or here: Tertullian Apology First Sentence Handout.