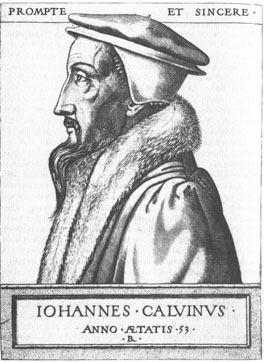

When a theologian comes up with a way of structuring the presentation of Christian doctrine, sometimes it just catches on and gets used by theologians of very different traditions. Take as an example John Calvin’s way of describing Christ’s work as the mediator: reflecting on “Christ” as “the anointed one,” Calvin asked, “what kind of person gets officially anointed?” His answer, straight from Old Testament theology, was “Prophets, Priests, and Kings.” Though Calvin wasn’t the very first to say this (it goes back to Eusebius in the late 3rd century, I think), he was the first to use the idea of Jesus Christ’s triplex munus, threefold office, as a way of organizing a great deal of theological material.

The triplex munus caught on: Reformed theologians latched onto it right away, but soon even the Lutherans were using it, and the next thing you know, it’s showing up in Roman Catholic writings. John Calvin paid close attention to Scripture, found a helpful way of articulating what he saw there, and there was a rapid, but unofficial, ecumenical acceptance of this teaching.

I was reminded of this recently while looking something up in Mysterium Salutis: Grundriss Heilsgeschichtlicher Dogmatik, a multi-volume, multi-author Roman Catholic theology from the period just after Vatican II. The plan of this massive German work was to organize everything in Catholic theology around the leading idea of salvation history (heilsgeschichte, the economy of salvation). It was hoped that this would put some life and movement back into the schematic categories that conventional Catholic theology was comfortable with.

It would be reasonable to assume that this movement toward salvation historical categories had developed out of the previous decades of careful historical work done by the group of Catholic thinkers known as the nouvelle theologie movement (Congar, Danielou, de Lubac, etc). That, plus Vatican II, is what I had always assumed was behind Mysterium Salutis.

But in the introduction to volume I, the editor credits a Lutheran observer at Vatican II, whose constant commentary on the council’s proceedings kept redirecting the attention of the expert theologians back to salvation history. The Mysterium Salutis project, according to its editors, has its origin in admitting that the Protestant observer was just plain right about his observations. A good idea is just a good idea.

Which brings me back to the sixteenth century. Not too long after Calvin put the threefold office of Christ into circulation as a great way to order the doctrines of christology and soteriology, Ignatius Loyola started making use of ordered meditations on the discrete events of Christ’s life. Loyola directed users of his Exercises to ponder these mysteries of Christ’s life one after another, sort of like beads on a rosary. No, pretty much exactly like beads on a rosary. As was the case with Calvin, Loyola didn’t invent this system (it’s remarkably similar to iconographic programs, if nothing else), but he put it into a classic form that proved contagious for later theology.

The topic “mysteries of the life of Christ” has, however, largely remained a Catholic phenomenon, and I’m hard pressed to think of examples of Protestant theologians making much use of it. As an ordering principle for handling the mass of material that needs to be presented in christological reflection, I think it is a very promising schema.

Perhaps a Protestant appropriation of it would involve linking it to the text of a gospel, preferably not a harmony or a lectionary/liturgical cycle. I can envision a variety of ways of working through the events of a gospel, using “the mysteries” as theological skylights opening out from the narrative onto the whole doctrinal framework. Such a treatment could be the backbone of a seminary curriculum which is ample enough to do justice to biblical studies and theology at once. How it could be put between the covers of a systematic theology is another story, but a good idea is a good idea. I would like to see a Protestant systematic theology that gave this schema a real workout.