There is an argument about the American founders which is always going on somewhere, and is never productive.

First speaker: “This is a Christian nation, with a Christian founding, and the religion reflected in all of our founding documents is Christianity. None of our polity makes sense without the Judeo-Christian origins.”

Second speaker: “This is an Englightenment nation, whose major advantage was that it had the good fortune to be designed by rationalists to keep church and state separate, and to keep religion a private affair.”

First speaker: (produces reams of documents showing Christian influence on American ideals)

Second speaker: (cites Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, etc.)

First speaker: “It’s so Christian!”

Second speaker: “It’s so not!”

Leaving these two characters to their own discussion (don’t worry, it’ll still be going on when we get back), we can save the whole subject with a little bit of nuance.

Let’s say you start with a chemically pure version of the Christian faith, in which you’ve isolated the thing itself and removed any contaminants. Then you put that into circulation in the late eighteenth century, when certain crying political needs are being felt. What you get is a particular application of some useful Christian ideas to the needs of the time. The resulting political/cultural/economic entity is a hybrid. The idea of America assembled by the founders has elements of its Judeo-Christian heritage (which is why Speaker 1 can go on forever without saying anything false) and elements of Enlightenment political theory (which is why Speaker 2 can do likewise). These two influences react on each other in unprecedented ways, and the hybrid turns out to be a vigorous and apparently stable organism.

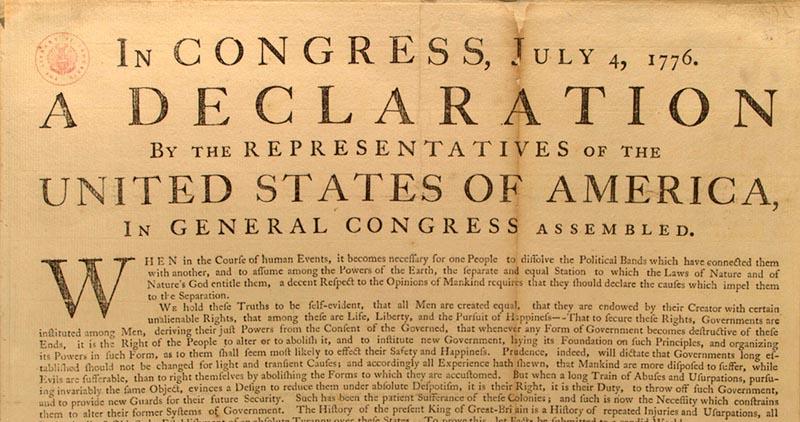

Take as a case study the theology of the Declaration of Indpendence.

What is the doctrine about God that is operative in this founding document? The principal wordsmith was Jefferson, who was personally offended by the doctrine of the Trinity but had large views on religious tolerance (“It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”). When God shows up in the Declaration, there are four main descriptions given of him:

1. Nature’s God (makes laws, the “laws of nature,” which entitle a people to freedom)

2. Creator of humanity (who endows men with unalienable rights)

3. The Supreme Judge of the world (keeps an eye on the right intentions of all)

4. Divine Providence (can be relied on to protect the innocent)

If you look harder, you can find more about God in the Declaration: He’s hiding in a lot of the big solid nouns that form the substantive vocabulary, underwriting notions like “duty.” Taken together, these phrases describe a God who functions in the American system as the ultimate source of human rights and responsibilities.

On the other hand, this Official God of the Declaration is a far cry from the character revealed in the New Testament. To test this, try addressing the Lord’s Prayer to God as conceived of in the Declaration: “Our Supreme Judge, who art in heaven, providence be thy name;” etc. Nature’s God, the creator, is not specific enough to be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the first person of the Trinity, the one who so loved the world that he gave his only son.

If this God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in unity, he’s a God who’s not mentioning anything about it. In fact, he’s not mentioning anything: He seems to be the God we can know without any revelation, the God who can be known by human reason functioning properly and interpreting its own existence rightly. We must all come from some source, says Enlightened reason, and that source must be the basis of our sense of right and wrong, the foundation of rights and duties, the force which guides human history through wars, nation-building, and kings good or bad.

That’s a theology. It’s not simply identical with Christian theology, and it can even lead to some interesting tensions which will need to be negotiated (in the age of Lincoln and today). What, for example, can one count on divine Providence to do, if by “divine Providence” you mean something God’s not revealing anything about? Now there’s a question that reveals the gap between the God of the Declaration and the God of the New Testament.

From the Christian point of view, the New Testament obviously says a lot more, and better things every way, than the Declaration can say about God. The Declaration, in fact, is a kind of limitation, selective extrapolation, and exploitation of a few resources from the New Testament, or rather of a vigorous Protestant understanding of the New Testament.

Protestant theologian Karl Barth once compared the Declaration of the Rights of Man to the Declaration of Indpendence, probed their theologies, and concluded that “the Calvinism gone to seed of the American document still distinguishes itself favourably from the Catholicism gone to seed of the French one.” It’s worth remembering that the God of the Declaration (Nature’s God, the Supreme Judge, our creator, divine Providence) is based loosely on the God of Calvinism –that’s good. But it’s a Calvinism gone to seed –that’s bad. The resulting gap between Gods should not be shocking. It’s the gap between the the earthly city and the heavenly, reflected and refracted in a uniquely American form.