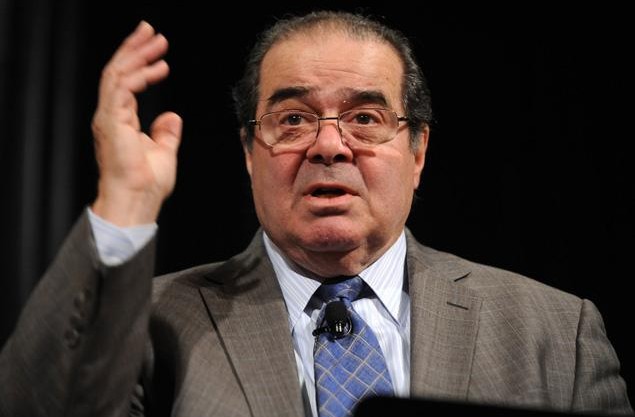

My guess is that Antonin Scalia has newfound sympathy for Terry Lee Collins, that hapless anti-hero of the 2001 crime caper, Bandits. Chagrined at the predictable shenanigans of his co-conspirators, Terry carps, “You know the hardest thing about being smart? I always pretty much know what’s gonna happen next. There’s no suspense.” For the last several months the nation has been waiting to see what the Supreme Court would do with the gay marriage cases. Justice Scalia knew a decade ago.

My guess is that Antonin Scalia has newfound sympathy for Terry Lee Collins, that hapless anti-hero of the 2001 crime caper, Bandits. Chagrined at the predictable shenanigans of his co-conspirators, Terry carps, “You know the hardest thing about being smart? I always pretty much know what’s gonna happen next. There’s no suspense.” For the last several months the nation has been waiting to see what the Supreme Court would do with the gay marriage cases. Justice Scalia knew a decade ago.

In 2003, Scalia observed that the Supreme Court’s extension of constitutional protection to homosexual sodomy in Lawrence v. Texas logically necessitated the constitutional establishment of gay marriage. Justice Kennedy, writing for the Lawrence majority, assured the American people that the Court’s ruling “[did] not involve” the issue of gay marriage. “Do not believe it,” Scalia insisted. Given that the Court refused even to consider that there might be a rational basis for the traditional moral norms reflected in Texas law, there could likewise be no defensible reason to exclude gays from “any relationship that [they] seek to enter.” Without a legitimate reason to restrict homosexual conduct and relationships, traditional norms must be based on raw prejudice, reflexive disgust, or worse, downright “animus” (as the Court opined in Romer v. Evans (1996)). And clearly such motivations will not pass Constitutional muster (not to mention satisfy common decency).

With the release of the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v. Windsor a couple of days ago, Justice Scalia’s prediction has been all but vindicated. The Court stopped short of declaring a constitutional right to gay marriage; however, Justice Kennedy (again writing for the majority) carried the essential argument of Lawrence forward to strike down §3 of the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). This provision defines marriage as the union of one man and one woman for the purposes of federal law. (DOMA’s other main provision (§2) holds that states do not have to recognize definitions of marriage adopted by other states, and this was left intact for the time being.)

Now, technically Windsor is more about federalism than it is about constitutional rights or marriage equality. The case involves a lesbian widow whose same-sex marriage (originally performed in Canada) was recognized under New York state law. When she tried to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses she was barred by DOMA. New York says she was married; Washington says she wasn’t. Which is it? The Windsor Court was unwilling to subject citizens in states that recognize same-sex marriage to a dual status: married at home, but single in the eyes of Uncle Sam. The regulation of domestic relations, the Court argued, is “an area that has long been regarded as a virtually exclusive province of the States.” Although the federal government is not completely excluded from regulating marriage, DOMA impermissibly infringes on state prerogative by subjecting citizens within a single state to conflicting schemes of marriage and thus introduces instability and unpredictability into a basic human relationship. Therefore, the problem with DOMA is that it violates the Constitution’s federalist principle, i.e., it interferes with traditional state powers. This seems to mean that the states are still free to define marriage according to the traditional heterosexual norm. And indeed, Justice Kennedy ends the opinion affirming as much. Chief Justice Roberts is also careful to point out in his dissenting opinion that the Court nowhere considers or rules upon whether states may continue to employ the traditional definition of marriage. “I think the majority goes off course, as I have said, but it is undeniable that its judgment is based on federalism.”

Unfortunately, this is only half the story. Packed into the federalist structure of Windsor is a rejection of the purpose and content of DOMA “quite apart from principles of federalism.” This line of critique, as Scalia anticipated, is simply an elaboration of ideas established in Lawrence. Here again, Kennedy declined to consider the possibility that Congress (and then President Clinton) had even a minimally rational basis for enacting DOMA. Such explanations are not difficult to produce, e.g., uniformity in federal law, stability of reproductive relationships, etc. Nevertheless, Kennedy brushes past these possibilities to attribute irrational and malign motives to DOMA’s framers. Whereas New York acted to “enhance[] the recognition, dignity, and protection” of gays, proponents of traditional marriage were activated by a “design[] to injure the same class the State seeks to protect.” Windsor is replete with such disturbing attributions. The “avowed purpose” of the bill was to “disapprov[e],” “disadvantage,” “stigma[tize],” “disparage,” “demean,” and ultimately “humiliate” gay Americans and their children.

The upshot, of course, is that we face not a civil dispute over competing definitions of marriage (as Justice Alito suggests in his dissent), but rather a concerted effort by moral traditionalists to marginalize a minority on the basis of irrational prejudice and ill will. Framed in this way, the path from Lawrence to Windsor and ultimately a constitutional right to same-sex marriage is inevitable. Assurances along the way that Lawrence doesn’t entail Windsor or that Windsor’s federalism won’t collapse under the weight of its condemnation of the traditional understanding of marriage are specious at best.

Yet this is not to say that same-sex marriage is a fait accompli. Necessity in logic doesn’t amount to necessity in fact, and Chief Justice Roberts was right to reiterate the limited holding in Windsor. Regardless of what the liberal bloc of the Roberts Court will do if given the chance, the fact is that right now the Court has left the definition of marriage in the states’ hands. The question of what marriage is is still open to democratic debate, and as some commentators have recently observed, the Court is likelier to continue to defer to democratic debate if they can see there is democratic debate to defer to. It is therefore incumbent upon supporters of traditional marriage to continue to advance reasoned arguments in the public square. To this end, books like What Is Marriage? Man and Woman: A Defense, co-authored by Sherif Girgis, Ryan T. Anderson, and Robert P. George are more important than ever. I’ll be discussing their arguments in an upcoming post.