The Chalcedonian definition draws boundaries which clearly mark the limits within which orthodox thinking on the incarnation can take place. I’ve written about the greatness of Chalcedon elsewhere.

But it is one thing to praise Chalcedon for doing this boundary-drawing, and another thing to say that this is all Chalcedon does. There is no need to emphasize the negative, neutral, and empty character of the definition. The conventional wisdom of modern theology has usually treated Chalcedon in the latter way, as a self-canceling exercise in manipulating the conceptual categories of nature and person. It is fashionable among those who consider Chalcedon worth investigating at all (never mind those who do not) to think of the definition as having played itself out with its dialectical self-negations, so that now it serves as a venerable historical landmark and an invitation to do something new.

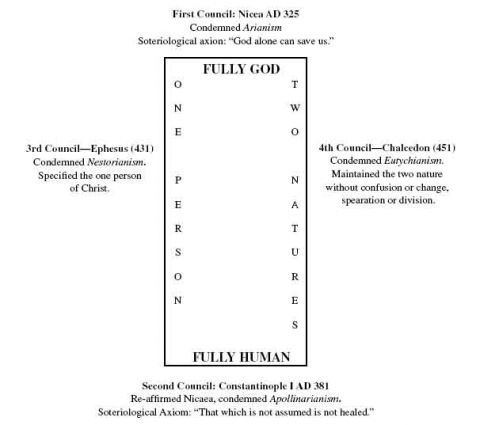

If the two natures (divine and human) and the four negatives (no confusion, no change, no division, no separation) mark the edges of the field, is there anything in the center, or is that the free zone for novelty and creativity in theological work today? I believe there is something already there at the center, and that the Chalcedonian boundaries were established by the ecumenical councils in an awareness of what was at the center. When the bishops gathered at the councils, their tradition was to set up the book of the gospels in the seat of authority, and after Nicaea, the top item on the agenda of each subsequent council was to re-affirm the faith of Nicaea.

At the center of the open space marked out by the boundaries of Chalcedon are two things: the apostolic narrative of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the confession that this person in the gospel stories is an eternal person distinct from the Father yet fully divine. What stands in the middle of the Chalcedonian categories is the biblical story of Jesus, interpreted in light of the Trinity. If we find the gospel and the Trinity stationed inside the Chalcedonian boundaries, what is it that we as theologians and Christians are supposed to do with them?

If Chalcedonian logic is right, so far as it goes, then it requires us to take the next step. However, the “step beyond Chalcedon” that I am advocating is not the sheer backwards jump of a return to the Bible —though that will be necessary and fruitful with the lessons learned from conciliar christology. It is also not a sheer forward jump to new theological construction —though opportunities are likely there as well. Instead, the step beyond Chalcedon that I am advocating goes directly along the trajectory Chalcedon had already been following, and is nothing more than another step along the road of conciliar christology, from the fourth council to the fifth; from Chalcedon in 451 to Constantinople II in 553.

Furthermore, the step taken by the fifth council is itself not a new departure, and does not posit any new information beyond what is implicit in the Chalcedonian definition. What the fifth council (Constantinople II, 553) does is make explicit and thematic once again the trinitarian theology that has been the background of all four councils so far. It does this in three ways: (1) by bringing christological and trinitarian terminology together, (2) by giving priority to the person in christology, and (3) by telling the long story of salvation. I’ll say more about each of these in a future post.

Trinitarian theology has been the background of the christology of the ecumenical councils all along. Christoph Schwöbel argues that this should have clued theologians in on the way Chalcedonian concepts were intended to work: “The fact that the clarification of trinitarian logic of the Christian understanding of God preceded the attempt at defining the boundaries of orthodox Christology should be seen as an important hint that elucidation of the doctrine of Christ necessarily presupposes the trinitarian understanding of God as its basis.” Consider the fact that the first thing the Nicene theologians had to do was make statements which straddle the line between christology and the doctrine of the Trinity. To which category should we assign the confession, “Jesus is homoousios with the Father?” It is simultaneously christology and trinitarianism, or better, it is christology in trinitarian perspective. Brian Daley has issued a salutary warning that

“Trinitarian theology” and “Christology” are modern terms, not ancient ones, and represent tracts in the theological curriculum of the modern Western university rather than categories of patristic discussion. Both of them are really about one thing: the distinctively Christian understanding of how God is related to the world and to history; how God can be both transcendent Mystery —ultimate, infinite, free of creaturely limitations, uncircumscribed by human thought—and also “Emmanuel,” God-with-us, God personally encountered in Jesus, God speaking today in the scriptures and in the church. (Brian E. Daley, S.J., “One Thing and Another: The Persons in God and the Person of Christ in Patristic Theology,” Pro Ecclesia 15/1, 17-46, at 42.)

So the ecumenical councils were working both doctrines at once, because they were engaging the whole matrix of Christian thought at the level of the primal unties where the doctrines of God, Christ, and salvation are all mutually implicated. That step beyond Chalcedon is the step that theology needs to take in our own time. The good news is that the fifth council already took that step, so we can learn from it as we do our own theological work.

This is the sixth in a series of posts on the christology of the ecumenical councils. Here are the others:

The value of conciliar christology

The Council of Nicaea in 325

The Council of Constantinople in 381

The Council of Ephesus in 431

The Council of Chalcedon in 451.