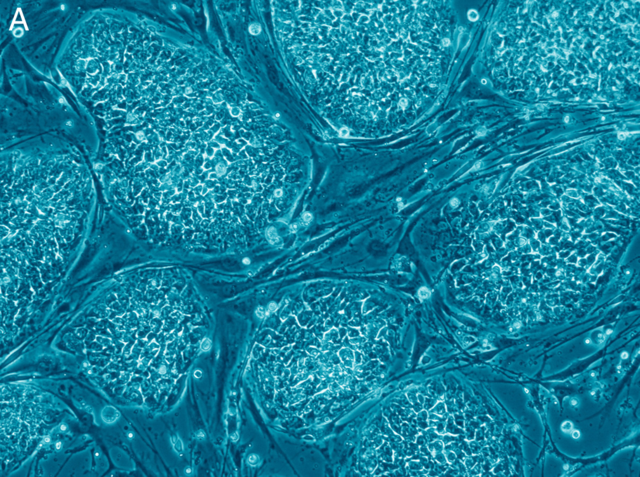

As I was driving around LA the other day listening to NPR, two stories run back-to-back caught my attention. The first was a story about the recent Nobel-prize winners John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka, who have uncovered a means for turning any cell into a stem cell from which an organ or even a clone may be created.  The NPR correspondent speculated about possible future ramifications of this capability (for instance, a desperate fan stealing a hair off of Brad Pitt’s head in order to grow her very own Brad Pitt baby).

The NPR correspondent speculated about possible future ramifications of this capability (for instance, a desperate fan stealing a hair off of Brad Pitt’s head in order to grow her very own Brad Pitt baby).

The next story was about a study done by Yale and the National Institute of Mental Health that determined that the club drug Ketamine is capable of treating clinical depression in a matter of hours, rather than weeks like Prozac. Ketamine increases connections between nerve cells, connections that become weak in patients suffering from depression, and so cause the patients synapses to imitate a healthy brain in a matter of a few hours.

Listening to these two stories in tandem elicited in me, as it would any lover of apocalyptic science fiction, immediate meditations on Aldous Huxley. After all, what characterizes that future civilization of Brave New World? The population is made-to-order in vitro, and there’s a drug called soma that artificially elevates mood without side effects or crashes. These, along with a sexual revolution, are all it takes to create the world that makes John “the Savage” despair.

So, technologically we’re there. Huxley’s world is probably about five years of intensive research from becoming a reality. This seems like a good time to rehearse the 6 best reasons not to capitalize on all the powers our new technology will bring, brought to us by the foresighted folks of sci-fi.

1. Brave New World taught us that sooner or later the genetic engineers and the social engineers will get together and decide how many neuroscientists and how many garbage men are needed, which is great if you’re the neuroscientist.

2. The Island taught us that organ farms have feelings too, and that your spare organs might just chase you, fake your accent, and get you shot.

3. 1984 and Minority Report taught us that getting tailor-made ads beamed at you in a shopping mall (something else recently developed) makes it tough to blend into a crowd, and that the better technology gets, the easier it is to control society and silence troublemakers.

4. Gattica taught us that even well-intended genetic tailoring can be tyrannical. Giving a child six fingers on each hand so that he can be a concert pianist just might limit his paths in life. It’s a bit like living and working in buildings built in the 70’s — we’re forced to live inside somebody else’s aesthetic. Imagine if it were your body.

5. Ender’s Game and The Matrix teach us that the real world and virtual reality are hard to tell apart, especially as virtual reality becomes more lifelike. But the only world you can actually live in is the real one.

6. Serenity and Brave New World teach us that some drugs intended to manipulate human behavior for the better don’t. Soma might seem like a great idea, but it will destroy a society’s wisdom in the midst of assuaging its pain. And according to Serenity, if you try to eliminate a society’s aggression, you might end up dissolving the society altogether.

There’s an old argument about whether humankind ought to pursue new technology for its own sake. In his New Organon, Bacon says “Only let the human race recover that right over nature which belongs to it by divine bequest, and let power be given it; the exercise thereof will be governed by sound reason and true religion.” Bacon was confident that man is meant to have power over nature, and that we’d naturally use it wisely. The idea is that no new breakthrough is bad, that knowledge for its own sake is always worth having.

Maybe that’s true, but in The Abolition of Man, Lewis warns that man’s quest to conquer nature necessarily includes man attempting to conquer human nature, altering the elements of our genetics and environment that hold us back. But, as our science fiction friends have kindly pointed out, “fixing” human nature is ultimately nothing more than some people designing other people according to their own preferences and values. “Conquering” human nature means learning how to control genetics and environments, but who decides which human characteristics constitute the problem?

Power over nature is often, maybe always, power over someone else, whether it’s someone down the street, or someone one hundred years into the future living in the world we created. We are capable of helping or harming that future generation with the technology we produce today, but maybe our highest goal ought to be to refrain from conquering it.