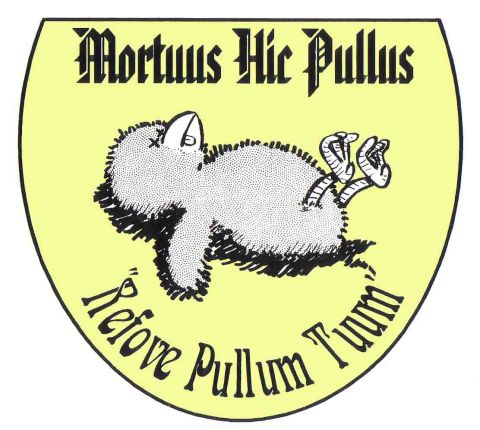

Reading hundreds of pages of theology every day, I was in a small group of friends in graduate school who helped each other study. We didn’t have much in common except for the looming doctoral exams, and some overlap in our reading assignments. Tired of saying “the group” is getting together, we named ourselves The Dead Chickens. I was a part-time cartoonist back then, so I designed a little logo featuring a dead chick and the Latin mottoes, Refove pullum tuum and mortuus hic pullus.

Reading hundreds of pages of theology every day, I was in a small group of friends in graduate school who helped each other study. We didn’t have much in common except for the looming doctoral exams, and some overlap in our reading assignments. Tired of saying “the group” is getting together, we named ourselves The Dead Chickens. I was a part-time cartoonist back then, so I designed a little logo featuring a dead chick and the Latin mottoes, Refove pullum tuum and mortuus hic pullus.

Why?

Because early in our reading labors, somebody had brought in one of the prayers of St. Anselm, in which he prays to Christ in these unusual terms:

Christ, my mother,

you gather your chickens under your wings;

this dead chicken of yours puts himself under those wings.

For by your gentleness the badly frightened are comforted,

by your sweet smell the despairing are revived,

your warmth gives life to the dead,

your touch justifies sinners.

Mother, know again your dead son,

both by the sign of your cross and the voice of his confession.

Warm your chicken, give life to your dead man, justify your sinner.

The prayer is partly based on the biblical image of God protecting his people “with his feathers and wings” (Psalm 91:4), and partly on the ancient idea that baby chickens died and could be brought back to life by the mother hen’s body warmth. As for our study group, I suppose we must have felt pretty dead from all the reading, and even though “Christ as Mother Hen” is an image that gets sillier the longer you ponder it, I think we were dead chickens ready for some re-heating.

Once you have reason to notice the word “refove,” which should probably be translated “re-warm” rather than just “warm,” you start to see it all over the place in western church fathers. It’s got that “re-” prefix on the front of the Latin word fovere, which is something Ambrose of Milan asked the Trinity to do to those who pray. In Ambrose’s hymn Deus Creator Omnium, which Augustine quotes at the end of his early dialogue On the Blessed Life, he sings, “fove precantes trinitas,” or “care for those who pray to you, Trinity.”

Care for them, warm them, nourish them; it’s apparently a hard word to catch all the nuances of. I don’t know Latin grammar, so I’m guessing. But Robert J. O’Connell’s 1994 book Soundings in Augustine’s Imagination (Fordham U. Press, 1994) spends a whole chapter digging into the resonance and suggestiveness of this term in Augustine’s writings. In a chapter entitled “Fove Precantes, Trinitas,” he says, “Augustine’s literary skill is never more masterfully displayed than in producing the luxuriant bouquet of images depicting God’s poignant care for fallen humanity. And it testifies to his imagination’s amazing fertility, as well as to its dominantly literary character, that so many of those images seem to have been triggered by a single Latin word —fovere.”

So Ambrose ended a hymn with it, and Augustine picked it up and developed it considerably for Christian use. That means that by the time Anselm used this tender word in his chicken prayer, it had a whole heritage in Latin theological usage. But probably not associated with chickens.