But the most important part of Rembrandt’s magic was not his ability to do anything, but his restraint. He was willing to work within limitations that a lesser artist would have considered brutally restrictive. For that reason, even though you must see his large portrait paintings to see his full range, you can actually learn more about his particular genius from his printmaking.

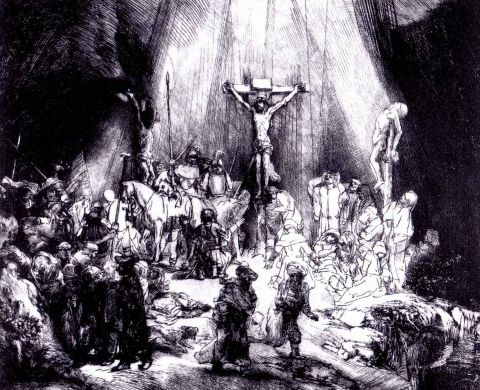

Consider the image above, The Three Crosses (click here for a better image from the Rijkmuseum’s site). The Rijkmuseum’s catalog says it is his “greatest and most dramatic print,” calling it “a work which has all the power of a painting.” It is a drypoint, a kind of engraving in which the artist scratches lines into a metal plate and then prints from that metal plate onto paper. It is a very limiting technique, reducing the artist to use nothing but inked lines. Rembrandt makes the most of those limitations, layering and cross-hatching his lines with great drama. He actually turns the linear character of the medium to his advantage, scratching the lines of light downward from the open heaven. He turns the image into a play about where the light is and where it is not. Artistically, this man who could paint anything reduced himself to the most basic of visual elements, and then worked those elements for all they were worth.

Rembrandt also exploited the possibilities of the drypoint printmaking medium. Having worked the metal plate to a finished state, he pulled several prints from the plate. But then he re-worked the plate, adding more dark lines on top of the image, and pulled another set of prints from that state. Then he did it again, reaching a third state. The image of Golgotha got progressively darker, as he added more and more lines to the image. In the years before photography, these printmaking techniques were the only way an artist could produce multiple versions of the same image. Rembrandt left us this great print in multiple states. State by state, he goes deeper into the darkness of the death on the cross.

The peak of Rembrandt’s power of living within limitations, though, is evident in his choosing and framing of the scene. Rembrandt knew his art history well, and knew all the tricks that previous artists had used to bring out the meaning of the death of Christ. Angels could fly around the cross, tearing their garments and weeping (as in Fra Angelico). God the Father could be enthroned behind or above the cross (as in Masaccio). The cross could be in the center of a cloudburst flanked by the shining hosts of heaven (as in Durer). The background could be solid gold (as in Byzantine panels). There could be halos, miracles, portents, and inscriptions telling who this man on the cross was.

But Rembrandt, characteristically, left out all those traditional visual markers of the theological meaning of the event. Instead, he portrayed what could be seen by the physical eyes of a common person at the scene, as interpreted by somebody who has the biblical account at the front of his mind. To anybody fluent in the visual language of the Christian tradition, Rembrandt’s refusal to deploy the elements of that language must seem like extreme asceticism, as if he were fasting from halos or epiphanies. Instead, Rembrandt gives us a sunbeam which might be nothing more than that to the naked eye. The holiness of the Son of God, like the favor of God the Father, is portrayed using such naturalistic means that it could be simple meteorological reporting. But of course it isn’t; those beams of light descending are the presence of God.

Similarly, the other two crosses in this “Three Crosses” image could just be two dead men, unedifyingly naked and beaten. The tradition of visual commentary suggests various ways to show that one repented and the other hardened his heart: Italian and German artists alike produced versions of this scene with the souls of the two men coming out of their mouths to be received by angels or devils. Look how Rembrandt sends his signals: the gesture of the man on our left is of despair, and he falls into shadow. The gesture of the man on the right, however, is of absolute surrender, and he is bathed in light.