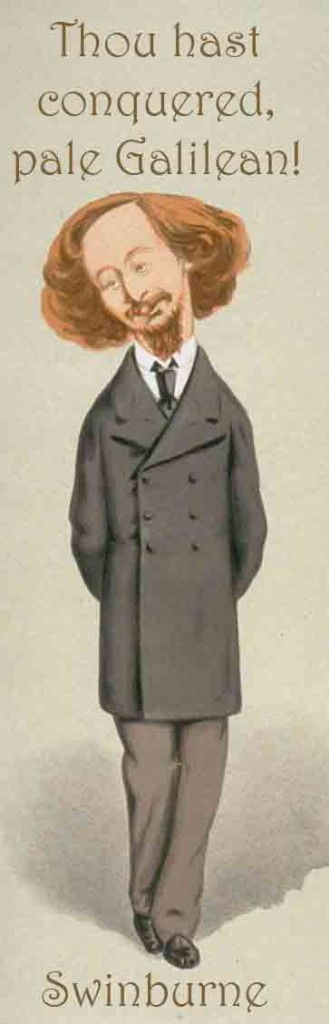

Today (April 5) is the birthday of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909), an English poet who was famous in his day but hardly remembered in ours. One of his best-remembered lines is about this very changing of times, in which mighty figures of one age are forgotten by the next. But the mighty figure whose rise and inevitable fall Swinburne prophesied was Jesus Christ.

Today (April 5) is the birthday of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909), an English poet who was famous in his day but hardly remembered in ours. One of his best-remembered lines is about this very changing of times, in which mighty figures of one age are forgotten by the next. But the mighty figure whose rise and inevitable fall Swinburne prophesied was Jesus Christ.

The lines occur in Swinburne’s 1866 “Hymn to Proserpine.” The sub-title of the poem is “after the proclamation in Rome of the Christian Faith,” and the epitaph is “Vicisti, Galilaee,” which were supposed to be the dying words spoken by Julian the Apostate, the last pagan emperor of Rome. Constantine had already set the empire on its path to Christ, and Julian had self-consciously set out to turn Rome back to the worship of the old gods. In legend and in Swinburne’s poetic crafting of the scene, Julian had challenged the faith of Jesus to a fight, and had to admit defeat with his dying breath: “Vicisti, Galilaee.” Or, in Swinburne’s longer version:

Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath;

We have drunken of things Lethean, and fed on the fullness of death.

Never mind that it was a case of the pot calling the kettle pale; little Algernon was a small (just over 5 feet), thin, pasty, fair-haired fellow. And “swarthy Galilean” probably didn’t scan as well. Nor did it make the point that Swinburne wanted to make: That paganism was great, lusty, life-affirming, and vigorous, but Christianity sucked the life out of it and left everything behind it dead. “Pale Galilean” seemed to describe all that Swinburne and his ilk hated about Victorian Christianity, and soon Nietzsche would be taking his turn at calling Christianity the ultimate form of life-denial. It was a critique the world-weary age was ready to hear, even if they didn’t quite think they had the alternative worked out yet.

Swinburne’s emperor Julian took his stand against the rising Christian faith of the Galilean, and said defiantly:

Though all men abase them before you in spirit, and all knees bend,

I kneel not neither adore you, but standing, look to the end.

And he predicted that, just as pagan Rome fell when its cycle came around, the empire of Jesus would inevitably fall as well:

Though the feet of thine high priests tread where thy lords and our forefathers trod,

Though these that were Gods are dead, and thou being dead art a God,

Though before thee the throned Cytherean be fallen, and hidden her head,

Yet thy kingdom shall pass, Galilean, thy dead shall go down to thee dead.

Swinburne set his hopes on the collapse of Christianity, a collapse that he thought was inevitable because all gods fail. The two brief words of the dying Julian are elaborated in this long hymn to Proserpine, and it is Proserpine not so much as the goddess of Spring, but as the symbol of the cycle that includes universal death. This is who Julian, or rather Swinburne, turns to, “having seen she shall surely abide in the end; Goddess and maiden and queen, be near me now and befriend.”

Under the heading of “Decadents” in literature and life, Swinburne has a major entry. Things run downhill and fall apart; everything breaks up eventually; and we are living at a time when the crashing and colliding of dying systems and gods is ringing in our ears every day. This was his worldview, and he extracted whatever fin de siècle vigor he could from it. It’s not exactly what you could call hope, but it was a kind of artsy resignation that gave him the energy for remarkable craftsmanship in his poetry.

Swinburne suffered a breakdown in his early forties, related to alcohol abuse, general “nervous excitability,” and dissolute living of various kinds. He survived into his seventies, perpetually convalescing and cared for by a friend. We do not know his last words, though he had given much thought to Julian’s last words, and had even written a funny poem on “The Last Words of a Seventh-Rate Poet.”

Swinburne was no seventh-rate poet. He had the full blessing of the poet’s power to charm, which his contemporaries acknowledged whether they found his views scandalous or exciting. One critic said, “His poetry is like fairy gold. We dream that we are wealthy, but our wealth perpetually eludes us.”