On April 16, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote out by hand the document we know as the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, and now recognize as a classic text of American history, of civil rights history, of religious history. King was in jail for leading nonviolent protests against racial injustice in Birmingham, but what provoked him to write this masterpiece was not the turmoil of the protests themselves, not the unjust imprisonment, not his need to declare the justness of his cause to the general public. What prompted him was betrayal by white church leaders, who left him hanging.

On April 16, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote out by hand the document we know as the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, and now recognize as a classic text of American history, of civil rights history, of religious history. King was in jail for leading nonviolent protests against racial injustice in Birmingham, but what provoked him to write this masterpiece was not the turmoil of the protests themselves, not the unjust imprisonment, not his need to declare the justness of his cause to the general public. What prompted him was betrayal by white church leaders, who left him hanging.

King had been in jail since April 12 (Good Friday), and now a group of eight prominent white clergy had just published in the newspaper an open letter called the “Call for Unity,” urging Birmingham’s black and white Christians to stick together, resist the agitations of these outsiders (they did not mention King by name) who were stirring up dangerous trouble in their city, and to be patient. “We recognize the natural impatience,” they wrote, “of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized.” But this ecumenical coalition (bishops of the Episcopal, Methodist, and Roman Catholic churches; a high-placed Presbyterian; a Baptist; a Rabbi), diverse in their ideas about race, were quite unified in their response to King’s nonviolent protest movement: “We are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.”

That context is important, because everything about King’s Letter is shaped by it being a response to the soft words of patience, unity, and Christian love being offered by the white churches. The Letter wouldn’t be as sharp if it weren’t polemically striking back against this particular enemy, and the best lines in the Letter get their energy from his rejection of false comfort offered in the name of religion: “‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.'”

It’s also what makes the Letter from a Birmingham Jail such a relevant document for white Christians more than fifty years later, and why Bryan Loritts has re-published the full text of the Letter in a new book from Moody just this month. If the white churches of 1963 were prone to say “Be patient; protest is dangerous,” the white churches of 2014 are prone to say “Didn’t we already achieve racial reconciliation a long time ago? What’s the issue?” So many of the mechanisms of deferral, denial, and indifference are structurally similar. King’s arguments in the Letter need almost no updating to speak a word to our situation.

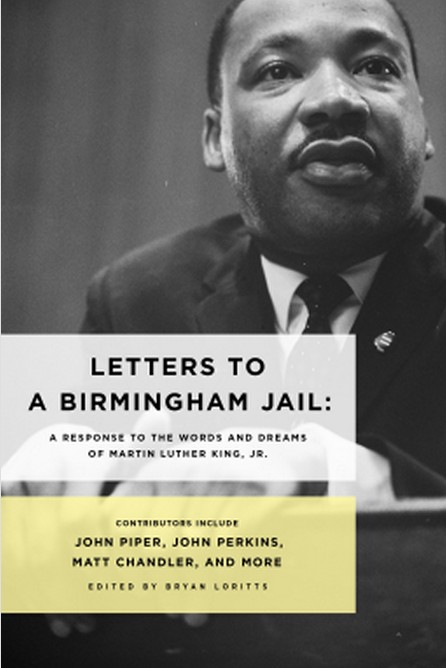

Almost no updating. But they do need some, and this book, Letters To a Birmingham Jail: A Response to the Words and Dreams of Martin Luther King, Jr, provides that updating in striking fashion. A group of ten pastors here actually write short personal letters to MLK, followed by one chapter each of personal reflections on the importance of King’s message. As editor, Loritts says he knew that “a black man writing yet another book on race and its tributary themes was not going to accomplish what I had envisioned for this project; there needed to be a multiethnic cohort of Jesus-loving authors who embodied and wrote in such a way that the broader culture was jolted out of her slumber.” So Loritts gathered them: black, white, and Asian, these writers respond passionately, echoing and amplifying King’s message for today’s church.

“Well, Martin, there’ve been a few risings and settings of the sun since you wrote your letter…” begins John Perkins, whose gift of understatement is on full display a little later when he simply says “I was tortured in the Brandon jail almost to the point of death” and then goes on with his story almost casually. If you don’t know John Perkins’ story, go and learn it. Here he gives only the bare outlines, along with a short form of his “three Rs” strategy of Christian community work. The book includes a link to a Perkins message at Veritas (that ends with Q&A), but aside from having the honored place of writing the opening chapter ahead of John Piper, this living legend makes his contribution quite humbly. Lean in and listen.

Piper is here, too, with a little bit of personal testimony, but a different agenda: “This chapter is not the story of John Piper’s racism and redemption. I told that story in Bloodlines. This chapter is the story of how to wait for God and hasten the day of multiethnic beauty.” The key word is “hasten,” as Piper insists that churches need to pay attention and take strategic action now.

Those are the two chapters that ought to guarantee that this book finds a wide audience, but there is great value in hearing from so many more as the book goes along. Each author (Matt Chandler, Soong Chan Rah, Charlie Dates, Albert Tate, Sandy Willson, John Bryson, and both Bryan and his father Crawford Loritts) testifies to their own experience of racial conflict and reconciliation; each articulates how the gospel connects to that story; each describes what they have heard in the message of the Letter From a Birmingham Jail. It’s an easy book to read, and it’s a little bit repetitive, but the repetition really does help drive home the point.

I was especially glad to see Ephesians 2 emerge as a common biblical source for the theology of race that the various authors developed. The various authors circled back to this crucial chapter again and again, and I think the reason is that Ephesians 2 is the most important statement in the entire Bible about the Gospel’s insistent demand for the wall between ethnic groups to come down. Other passages play their part as well; Bryson cites Paul’s verdict on Peter and his friends from Jerusalem refusing to eat with gentiles at Antioch: “Their conduct was not in step with the truth of the gospel.” His comment on this passage: BAM. Not exactly eloquent, but certainly powerful. But almost all of the authors dig deeper into Ephesians 2 as the key text, to good effect.

April 16 is the anniversary of the Letter From a Birmingham Jail. It’s the perfect day to check out this helpful offering from authors who take up the challenge and talk back to Martin Luther King, Jr about these important matters.