Angels are not mentioned in the scriptural account of the baptism, but they are almost always presented in the iconography.

Perhaps they are included because the baptism is read together with the temptation in the wilderness, which followed it immediately, and after which the gospels report that “the devil left Jesus, and suddenly angels came and waited on him (Matthew 4:11).” The curtness of this mysterious reference to angelic ministry in Matthew is reflected in the lack of clear function ascribed to the angels in the icons. Ouspensky sums up what can be said with certainty: “Angels take part in the holy ritual” (Ouspensky and Lossky, Meaning, p. 165). He notes that the texts for the liturgy refer to them, but these, like the Scripture itself, refuse to spell out the specific role played by the heavenly beings. Paul Evdokimov refers to them as “the angels of the incarnation,” the group of angels assigned to accompany the Word on his mission in the human world (Paul Evdokimov, L’art de l’icone: Theologie de la beaute, Paris: De Brouwer, 1970, p. 247). Details on this idea, including abundant patristic citations, may be found in Jean Daniélou, The Angels and Their Mission (Maryland: Christian Classics, 1991, 24-33). Pages 55-62 address the idea of angels assisting at Christian baptisms. Daniélou does not mention the angels at Christ’s baptism specifically.

Of course they execute the office one would expect them to in the presence of the Son of God: they adore him. Bowing their heads slightly and bending gracefully at the waist, they demonstrate for the viewer the reverence due to Christ. The only other action they are normally portrayed carrying out is holding liturgical cloths in their hands. These may be the garments which Christ has removed to step into the river, or they may be towels for drying afterwards. In the middle Byzantine image, especially as represented by the mosaic at Hosios Loukas, the cloths are extremely ornate. In some depictions, the cloth held by the angels is barely sufficient to cover their hands, and this may in fact be its primary function: covering the hands of the attendants in the presence of sacred objects. Contemporary liturgical practice is often the subtext governing how the ministry of the angels is to be understood, as the angels may be the special substitutes for deacons at this paradigmatic baptism.

The number of angels depicted varies. Three is always a good number, and is perhaps the number most frequently used. But examples of one, two, or four are easy to find, and even more than four are sometimes shown. The artist is free to add or subtract from their quantity depending on the amount of space available, or the relative compositional weight they can supply. The attention of the angels is fixed on Christ, or sometimes on the descending dove, or occasionally even on the space above the dove.

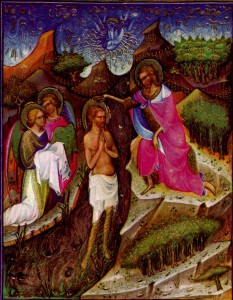

Angels, of course, change with the times in which they are painted. The Orthodox church has fairly well-established conventions for how they are to be depicted, so there is a great deal of continuity in their representation: flowing garments, sandals, wings, halos, and even a certain angelic hairstyle and pose remain constant. Piero Della Francesca’s Italian angels stand out as extreme examples of visual inculturation: they have wreaths, togas, blonde hair, and peacock-wings. They also seem to be casually talking amongst themselves rather than actively ministering at the baptism. Of the two angels in the Visconti Hours, one is turning his head away from the baptism, but he seems to be piously averting his eyes rather than sharing angel gossip. It is also interesting to note that the cloths held by these two brightly-colored Visconti angels can be distinguished: one holds a white garment, the other holds a green towel. El Greco’s lanky angelic host is a swarm of activity and adoration: they leap to Christ’s side with a cloth, throw up their hands in exultation, and spiral up into the heavenly throne room itself in their variously colored garments.

John was baptizing crowds of people when Christ came to him. For the most part, the classical iconography does not represent these people. They are clearly optional, and some would even argue that they are best omitted. Constantine Cavarnos, having advised against adding too many fish, recommends likewise that the crowd of people, the swimming children, and other such elements are best left out, all for the same reason: “It is contrary to the principle of simplicity, bringing in things irrelevant and distracting.” (Constantine Cavarnos, Guide to Byzantine Iconography, Volume 1, Boston: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 1993, p. 148). Nevertheless, a few onlookers sometimes make their way into these scenes, and not only in later images verging on the folksy. The mosaics at Moni Daphni and Nea Moni both show spectators in the background. At Moni Daphni only their busts have survived; they are two men who are in conversation with each other but seem amazed by the event transpiring before them. The Nea Moni mosaic is by comparison almost perfectly preserved. The two men are present, hidden partly behind a little rocky hill. They have been identified as disciples, specifically Andrew and John (Mouriki, Mosaics of Nea Moni, p. 126). Similarly, Giotto places two human witnesses at the baptism, but they are male and female, and the man bears a halo.

We might well ask, with Cavarnos, whether even Giotto’s or Nea Moni’s judicious inclusion of a select few spectators already violates the principle of simplicity. Why are they included? Perhaps they are intended to serve as witnesses with whom the viewer can identify. Paul Evdokimov, however, argues that John fills this role already: “In John the Baptist as archetype, as representative of the human race, it is all of humanity that is the witness of divine love” (Evdokimov, L’art de l’icone, p. 242). Or perhaps they are intended as worshippers, to pay due reverence to “the revelation of the worship of the Trinity” at this event. But certainly the angels have been the standard iconographic representation of worship since very early images. It is understandable that an artist might want to include someone of lesser stature than the martyr-saint John or the angelic host, someone the viewer could more easily identify with. Or perhaps it was felt that there should be actual empirical sinners present, since a central meaning of Christ’s baptism is the solidarity with sinful humanity which he actively took upon himself through it, “to accomplish all righteousness.” Whatever the reason, human spectators have frequently been included; sometimes entire crowds of them. Already at Nea Moni, in addition to the two disciples in the background, we see four young men in the foreground. One is swimming in the river and looking back over his shoulder at the others, who all seem to be intent on joining him: one has already stripped to the waist and is casting his clothes aside, another is tugging at his own garment, while the last one seems to be untying his red belt. Somewhat confusingly, these young men are the same size as the Jordan personification who is just a few feet away from them. A fifteenth-century Serbian icon shows four boys, already naked, leaping and diving into the water from the cliffs.

The river banks can sometimes be even more crowded than the water itself: In a seventeenth-century Greek icon, there are mothers on both banks of the Jordan, dipping their children into the baptismal waters. This same icon shows about a dozen people standing around watching the baptism. These crowds, as well as the swimming and diving boys in other icons, are probably best explained by the fact that there was an iconographic tradition sometimes observed of painting Christ’s baptism in a sequence following an image of John baptizing the people (Mouriki, pp. 124-125). In these earlier scenes, distinct groups were depicted in the context of John’s ministry: Jews coming to John for the baptism of repentance; religious leaders debating among themselves the validity of John’s message; and the mothers-dipping-babies and swimming boys we have already seen. These characters, who flourished when the baptismal cycle included two successive images, were later conflated into the scene of Christ’s baptism when the previous scene was eliminated. In the top corners is further evidence that this same icon is best explained in terms of multiple scenes being packed together in one image: at the left, John and Jesus pantomime their conversation about the propriety of Jesus receiving John’s baptism; while on the right a prophet holds his message scroll.

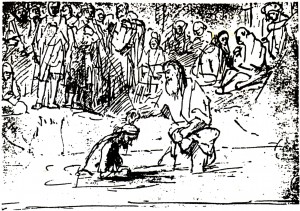

Later images, especially those which have a penchant for exchanging the Jordan for local rivers, likewise crowd the banks with updated, contemporary onlookers. The Tres Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry shows a sizeable crowd of medievals, but they are all dressed similarly and keep to the background. Later, Rembrandt would sketch a completely anonymous crowd as the backdrop for the action of the baptism, as would Gustave Doré in his own theatrical way. This collective anonymity contrasts sharply with Lucas Cranach’s treatment of the theme, in which the identity of the spectators is of paramount importance: Fully half of the scene is dominated by recognizable likenesses of the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, sharing the foreground with a conventional baptism of Christ occurring to their left. Cranach had the good sense to title his picture, “Allegory of the Reformation” rather than pretending it was an actual depiction of the baptism of Christ. He intended to show that the Reformation was the historic event of a remnant of faithful witnesses being present when God sent his Spirit to move upon the Word. Piero Della Francesca saw his chance to draw a classical disrobing male, and situated this figure fairly close to the Baptist. Finally, Nicolas Poussin provides such a welter of agitated participants that in the chaos of three men stripping, three men arguing, one man being awestruck by the voice from heaven, a boy clinging to an old man’s waist, and two sexually ambiguous but wingless attendants holding Christ’s garments, it is difficult at first to pick out the Baptist and Jesus standing by a still puddle. And there are a half-dozen more figures on the cliffs in the background!