Here is what I said (as best I can recall) at the ribbon-cutting ceremony on Friday, Feb 22 for the grand opening of Biola’s heritage room. The event was also the official release of the 100th anniversary commemorative book Rooted for One Hundred Years. I got to speak just after Dietrich Buss, history professor emeritus. I put it here on the blog because some of the remarks about how to handle a heritage should be applicable far beyond Biola.

Here is what I said (as best I can recall) at the ribbon-cutting ceremony on Friday, Feb 22 for the grand opening of Biola’s heritage room. The event was also the official release of the 100th anniversary commemorative book Rooted for One Hundred Years. I got to speak just after Dietrich Buss, history professor emeritus. I put it here on the blog because some of the remarks about how to handle a heritage should be applicable far beyond Biola.

==========================

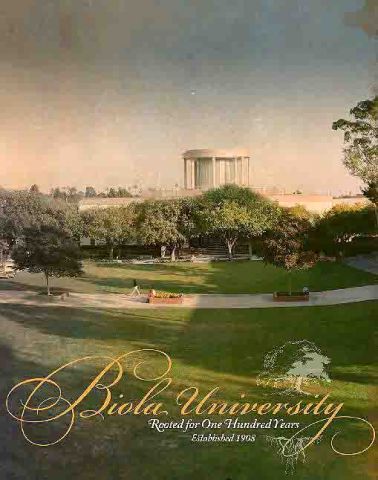

My name is Fred Sanders. I teach theology here at Biola, and I’ve been asked to say a few words introducing this book, Rooted for One Hundred Years. I’m pleased to do so, because while I had almost nothing to do with the production of the book, I am so glad to see it published. It is a fitting commemoration of Biola University’s century of existence; a big, attractive coffee-table book, a reflection on what the school has done down through these ten decades.

Rooted for One Hundred Years tells Biola’s story in 145 pages, which includes a running narrative and a whole lot of pictures. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this is a very long book indeed, because most of its argument is driven by a series of images that let us see what Biola meant to the men and women of its history. It’s a well-done yearbook for the century, and it shows that the Biola of today knows how to do right by its heritage.

In Genesis 25, Esau, the first-born of Isaac, is tricked into selling his birthright. Of course there were extenuating circumstances, chief among them being a very tricky younger brother who seemed to have Mom and God on his side every time Esau turned around. But the Bible makes it clear that Esau had fair warning and should have been on his guard against that grasping younger brother. Indeed, a formidable man like Esau would have been on his guard, if only he had thought more highly of his birthright and heritage. But he didn’t. He thought no more of his heritage than he did of some hot soup, so he traded his birthright for a mess of pottage. Famished one afternoon, he chose immediate gratification over permanent possession, and in the full scope of biblical theology, we can say he chose the temporal over the eternal, the physical over the spiritual. God doesn’t bless the Esau attitude: he hates it and calls it unholy.

Biola too has a birthright, a heritage handed down to us, toward which we will either be found faithful or unfaithful in future years. It is a heritage from visionary founders like Stewart, Horton, and Torrey, and the generations of workers who have added their own to this great communal project of education. It is a great heritage worth being proud of, and it stamps the whole 20th century as Biola’s century. When future historians reconsider the history of conservative Christianity in America in the 20th century, I believe they will have to give a more and more prominent place to the role played by this school. So far the historical bias has directed attention a little too far north, and way too far east, but that can’t last forever. A future history of evangelicalism will get it right, and get Biola a little more in the mix.

Not that we’ll ever be called the most important thing in this stretch of church history by anybody who’s got decent historical sense. Biola is not the most important thing going; it is not the center of God’s ways with the world; we are not the all-important cutting edge of Kingdom work in the world, or even in southern California for that matter. We’re just not that big a deal.

But we’re pretty cool. We’re not too shabby, you have to admit. We’ve got some great stuff going on at this University, with students streaming through year after year and alumni doing some valuable things. We’re not everything, but you’ve got to admit we’re really a part of the mix, and a pretty important one. The Biola story is a good one.

And aside from being a good story, it is our story. It falls to us to do right by this piece of evangelical history, because it’s our own heritage. We are the ones who should make the most of it, because it is in our hands to make something of. The great historian of Christian doctrine Jaroslav Pelikan once visited a senior scholar who had written a definitive book on the third-century theologian Origen of Alexandria. When Pelikan got to Denmark to meet with this scholar, you can imagine he was brimming with Origen questions and eager for the senior scholar’s insights. But he found that the man had long since turned his attention from Origen and had instead devoted his best efforts to studying a nineteenth-century Danish theologian named N. F. S. Grundtvig. Why, Pelikan, wondered, would you turn your attention from a formative early thinker whose influence on all subsequent theology is inescapable, to a recent figure important only to Danish Lutherans? The answer was: There would always be people studying Origen, but that it was up to Danish theologians to study Grundtvig. If Danes didn’t, nobody would.

Likewise, it falls to us to study Biola, to remember and understand what our predecessors have done here. If we don’t do it right, it will remain undone. And it’s worth doing, because the story is a good one. It’s a good slice of history, a whole century. That’s pretty old by California standards. By southern California standards, it’s positively ancient history. Rooted for One Hundred Years tells the story in its main outlines. The authors and editors had to leave a lot out, but they made good choices and put the right amount of attention in the right places. You’ll want to read it like you read National Geographic: first just the pictures, then the captions, and finally the story.

When I first got hired here, the first question I from friends elsewhere was, “Loyola?” The second question was, “Viola?” And the third question was, “Is there a book I can get to read a little bit about the history of Biola?” The answer to that question was, not really. There were 75th and 90th anniversary books, but they’re out of date and out of print. Now, thanks to Brenda Velasco, the Marketing/Communications department, and the Centennial team, the answer is that there is a book. Biola still needs a real institutional history to be written, something that digs in more critically, has room for more details, traces more connections, and names more names. But when and if that book is written, it won’t have this many great pictures. Good job, Biola 2008, at commemorating the previous century.