We are all past, present, and future. While our lives may be bound in the present, what constitutes our “who” has come before, and will be.

We are all past, present, and future. While our lives may be bound in the present, what constitutes our “who” has come before, and will be.

I am myself, my mother’s child, my child’s mother.

The intricacy and interdependency of human lives and human relationships are as complex as time itself, and authors who manage to tell stories that address both are rare. In some ways, their stories are like prophecies – reminding of us of what has been and what can be, will be, if…

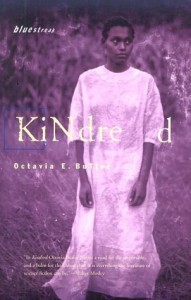

Octavia Butler’s speculative fiction work Kindred explores notions of identity in relation to the communal self, never losing the individual, but never prioritizing the individual apart from the community, however it is defined and delineated.

In Kindred a young woman name Dana, conflicted in her own time of space (a black woman married to a white man in 1970s Los Angeles), experiences the “before” that complicates the “now” that might just save the “then.” She is drawn back in time, again and again, to a world unlike her own; the 1800s for a black woman means slavery, brutality, shame and fear. Yet she is there because her own future depends on her actions in this past. In some ways it is a gift that gives her perspective on her actual present. To avoid spoiling a book that should be read for its beauty, suffice it to say, she leaves a part of herself in the past.

Dana as an individual matters. It is her life we follow when we read the story. But the communal self, the family she is a part of and, in many ways, must save, is also a central character. It is past, present, and future. Dana’s husband Kevin, also an individual, is shaped by the communal self as well – brought into a “who” that is chosen instead of biological, but no less actual and transformative. Butler did not try to explain why it is so, she only showed us that it is so.

Dana as an individual matters. It is her life we follow when we read the story. But the communal self, the family she is a part of and, in many ways, must save, is also a central character. It is past, present, and future. Dana’s husband Kevin, also an individual, is shaped by the communal self as well – brought into a “who” that is chosen instead of biological, but no less actual and transformative. Butler did not try to explain why it is so, she only showed us that it is so.

Many of Butler’s other works, such as the Xenogenesis trilogy or the Parable novels, take place in a possible future earth, future America, where humanity’s survival depends on understanding the communal self. Faith plays an active part of this survival, though it is not presented in a traditional Christian form.

Butler’s work is challenging, engaging difficult themes in speculative spaces in deeply human ways. Her vision of the world reflects humanity’s brokenness but preserves a hopefulness that salvation is possible, and that there is always faith. But faith is not merely an individual act. It is not individual salvation that Dana, or other of Butler’s characters, seek.

Individual salvation is pointless in light of the communal self; it is partial.

It is through this lens of the multi-layered communal self, present in nearly all of her works, that Butler could ask bold questions of society. She could write about the “-isms” that plague humanity both as an individual critic and as one who understood that she was a part of the communal self – responsible for her contributions to the whole.

The connectedness of souls that is present in Butler’s work reminds me of the connectedness of humanity writ large, but also of the unique connectedness of the Body of Christ. The actual singularity of our communal selves accomplished through the redemption that Christ brings is incomprehensible, yet salvation and this communal self are interdependent in the reality of the Church.

Butler’s works remind me to be present with the responsibilities this communal self entails.