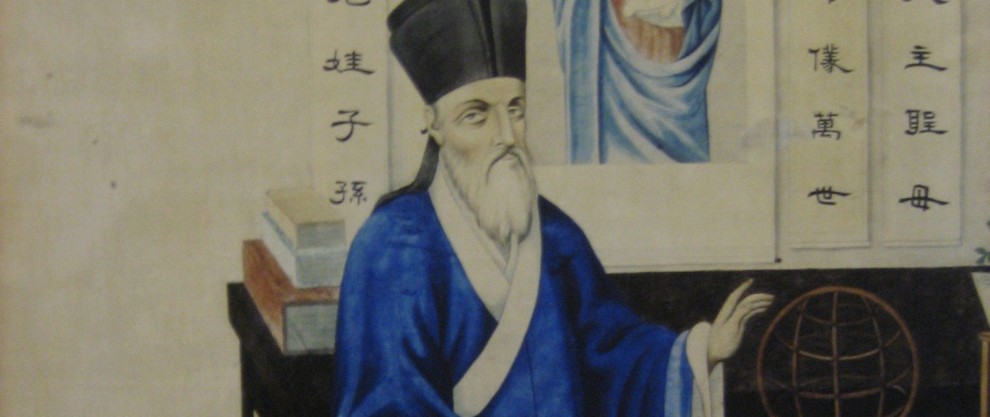

Matteo Ricci was the pioneer Jesuit missionary to China. He was born in 1552 and died on this day, May 11, in 1610. Ricci had to carry out his mission by making his way very delicately between two titanic forces: the imperial court of China, and the counter-Reformation papacy. Ricci respected the high culture of imperial China deeply, and of course like all the early Jesuits he was strictly, famously, loyal to the Pope. But in the difficulties of taking the Christian message to an ancient culture, Ricci’s work was always bumping into one or the other, or both at once.

The central issue was the Christian interpretation of Chinese culture. How should a Christian, especially one who is hoping to welcome Chinese converts into the church, think about the rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices of traditional Chinese culture? One obvious option was to condemn them: after all, these were clearly pagan rituals directed toward false gods, and a Christian missionary was calling for people to turn from their dead idols to serve a living God. Doing this would highlight the foreignness of the Christian religion, and make it seem that a person had to stop being Chinese in order to be a Christian. So the opposite alternative was to re-describe Christianity as compatible with, or as the fulfillment of, traditional Chinese religion. What you worship in ignorance, I declare to you.

Ricci took something of a middle course, but leaning more toward the second option. He seemed to think that eventually, Chinese Christians would recognize for themselves that burning incense to Confucius and their departed ancestors was superstitious. But in the meantime, he decided to interpret all of those practices as more civic than religious. Participating in these rituals was not so much idolatrous or even, necessarily, superstitious. It was just good Chinese citizenship.

This proposed solution was not immediately popular with anybody. A large and vocal group of Roman Catholic critics thought confucian practice was obviously pagan superstition and that Ricci was willfully blind to he idolatry he tolerated (the entry on Ricci in the 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia enshrines the mixed attitude toward Ricci in Roman Catholicism around the time of Vatican I, and gives some good detail about the friction with the Pope). The Chinese intelligentsia didn’t all take kindly to having their religion considered not really religious: when they said sheng they meant “holy,” but Ricci insisted they meant “venerable” in a broader, less clearly religious, sense. But Ricci also found support on both sides, and gradually a church formed, boasting 2,000 members by the time of Ricci’s death.

One of Ricci’s most interesting and enduring achievements was the way he used the Chinese language to clarify the idea of a personal God. He decided that the traditional Chinese expressions Shang-Ti and T’ien could mean not merely “heaven” but also “God,” and that Christians could use these words to translate the word “God.” He especially emphasized the term T’ien Chu, the Lord of Heaven, to put the personal God into Chinese categories. “Those who adore Heaven instead of the Lord of Heaven are like a man who, desiring to pay the Emperor homage, prostrates himself before the imperial palace and Peking and venerates its beauty.”