Charles Wesley doesn’t need anybody to stick up for him when it comes to Christmas songs: The man gave us Hark the Herald Angels Sing, after all. And if you add the Advent song Come Thou Long-Expected Jesus and a bunch of less famous but altogether worthy ones in the collection Hymns for the Nativity of our Lord, he’s got an impressive seasonal footprint.

So we can ungrudgingly turn our attention from the great Charles Wesley and share the Christmas cheer with the also-great Isaac Watts, giving him full credit for Joy to the World. It’s a song that ranks high on the Christmas hit parade even though Watts didn’t directly intend for it to be a Christmas song. It was actually his version of Psalm 98, or to be more precise, a hymnification of the second half of Psalm 98, which he produced while turning all the Psalms into gospel poems. Psalm 98 is about the coming of the Lord, so in a less-precisely-Bethlehemy way it does point to Christmas. Watts versified Psalm 98 wonderfully, and it stuck to Christmas time forever. But it started in Psalm 98.

And that brings us within range of the opening question: What if Charles Wesley turned Psalm 98 into a poem, too? Would it come out equally Christmassy?

Good question! And I’ve got the answer.

Charles Wesley didn’t work through the entire Psalter in quite the methodical way Isaac Watts did, but he came pretty close. So when somebody gathered all the Wesley-Psalms they could, they published The Wesleyan Psalter, which is “nearly the whole book of Psalms.” And Psalm 98 is there.

Which means, if you follow the thought, that Charles Wesley took on exactly the same assignment that Isaac Watts took on when he wrote Joy to the World.

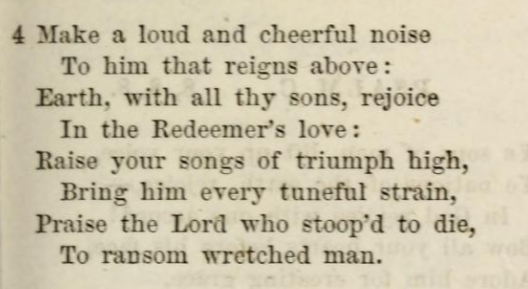

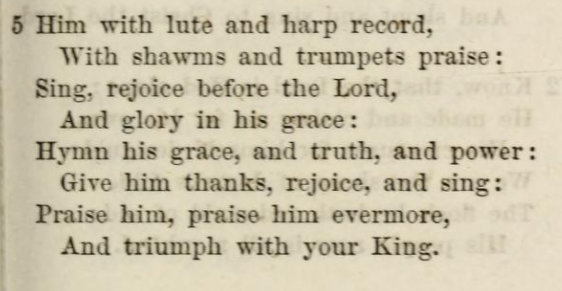

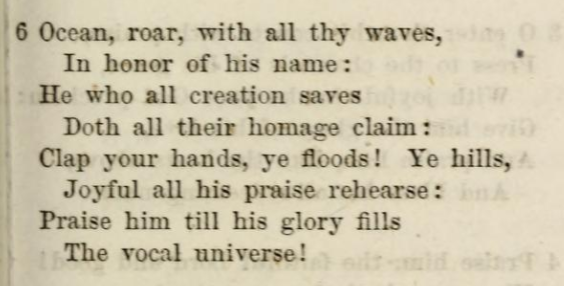

Here’s what Wesley came up with:

I’m not saying it would beat Joy to the World in a direct fight, but it’s pretty good stuff.

Watts and Wesley are both interested in the question of how the world itself can be said to sing, but I think they approach it differently. Watts answers with an echo: He sets up humans, “men,” as the ones who “their songs employ,” while the surrounding land and sea echo back that praise and “repeat the sounding joy.” Do the non-human creatures sing out in any deeper sense? Watts isn’t quite saying. Perhaps the blessings that go “far as the curse is found” reach all the way to “thorns” that “infest the ground.” That’s a powerful meditation on the effect Christ has beyond the human sphere.

Wesley, however, seems to go further. Motivated perhaps by the Methodist vision of inclusive atonement, he argues that “he who all creation saves / Doth all their homage claim.” That “all” that owes homage to the Lord somehow includes ocean, flood, and hills. For both Watts and Wesley, there are Christian theological reasons that explain Psalm 98’s call for the seas to roar and the trees to clap their hands. Wesley, however, is a bit more bold in saying that the trees and fields somehow, poetically at least, contribute their own voices rather than merely echoing ours. And as a result, the glory of the Lord fills “the vocal universe.”