Though the council of Trent was an event that sprawled over 18 years with long gaps between sessions (1545-1563), its canons and decrees were made official when the Pope received and ratified them by issuing a bull entitled Benedictus Deus on this date, January 26, 1564.

Though the council of Trent was an event that sprawled over 18 years with long gaps between sessions (1545-1563), its canons and decrees were made official when the Pope received and ratified them by issuing a bull entitled Benedictus Deus on this date, January 26, 1564.

The most headline-making issues at Trent had to do with the Roman Catholic response to the Reformation, which had been gathering strength since 1517. On all the major issues raised by Protestants, the Council of Trent drew lines of division and clarified the Roman Catholic position: on teaching authority, salvation, the sacraments, veneration of saints, etc. Protestant doctrines like the sole authority of Scripture, and justification by faith alone were declared anathema. With a clear statement from Rome on these issues, the sloppiness of regional variations on doctrine and practice was abolished.

As important as it was for Rome to respond clearly to the Protestant movement, however, more was going on at Trent than that. Considered in its own context, Trent can be seen as an official push for reform within the Roman church. In other words, while Trent was definitely Anti-Reformation in its central theological thrust, scholars no longer refer to it as part of the “Counter-Reformation” because that leaves out too much of what happened around Trent. Instead, the term “Catholic Reformation” has become the standard term. A catalog of all the initiatives undertaken and distinguished figures who prospered in roughly the period 1560-1648 is a remarkable record of Catholic confidence and zeal: Ignatius of Loyola and the Jesuit order require special notice. Roman Catholics did far better at sending missionaries to the new world in this early period than did the mostly land-locked Protestants. Among the other luminaries of the period are Vincent de Paul, Philip Neri, Louis de Granada, Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales, Bellarmine, Suarez, Petavius, and the scholars behind the long-needed revision of the Vulgate,. In art, there were Rubens and the Baroque; in music, Palestrina and others. There was also he inquisition, the index of forbidden books, and other hard-line developments which are a kind of negative witness to the zeal and self-assurance of the Roman Catholic revival movement. “The Catholic Reformation” is not an oxymoron, then, but a useful label to capture this 16th-17th century resolve on the part of the Roman Catholic church to be really, decisively, authoritatively Roman Catholic.

Twentieth-century Catholic scholar Yves Congar described the resulting establishment as Tridentinism, “an all embracing system of theology, ethics, Christian behavior, religious practice, liturgy, organization and Roman centralization.”

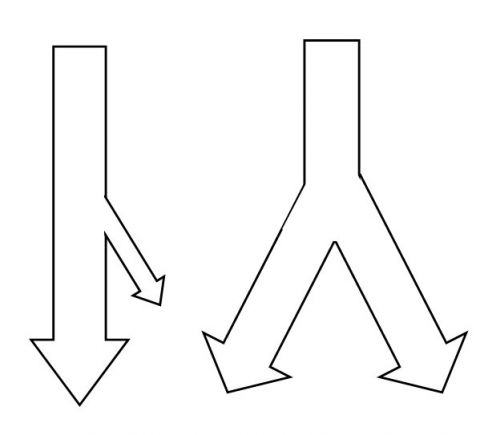

A kind of conventional wisdom traces church history down to the 16th century and then draws a Protestant spur diverging from the central line, a line labeled “Roman Catholic.” But considering the Tridentine (that’s the right word for “Trent-ian”) reorganization and consolidation of Catholicism in the sixteenth century, it’s just as accurate to draw that line of descent as an upside-down Y instead: What happened at the time of the Reformation watershed is that the Protestant churches organized as non-Roman Catholic, and the Roman Catholic church reorganized itself as anti-Protestant. What emerged from sixteenth century was not the Roman Catholic church doing fifteenth-century business as usual, but the Roman Catholic church reconstituted as the non-Protestant denomination. Tridentine Catholics might view that late 16th century entity as an improvement over the decadence of the late Medieval Roman church; and Protestants are more likely to view it as a tragic retrenchment into errors that should have been repented of, not institutionalized. They would also disagree about the amount of continuity and discontinuity there was between the Roman Church before and after the crucial period.

A kind of conventional wisdom traces church history down to the 16th century and then draws a Protestant spur diverging from the central line, a line labeled “Roman Catholic.” But considering the Tridentine (that’s the right word for “Trent-ian”) reorganization and consolidation of Catholicism in the sixteenth century, it’s just as accurate to draw that line of descent as an upside-down Y instead: What happened at the time of the Reformation watershed is that the Protestant churches organized as non-Roman Catholic, and the Roman Catholic church reorganized itself as anti-Protestant. What emerged from sixteenth century was not the Roman Catholic church doing fifteenth-century business as usual, but the Roman Catholic church reconstituted as the non-Protestant denomination. Tridentine Catholics might view that late 16th century entity as an improvement over the decadence of the late Medieval Roman church; and Protestants are more likely to view it as a tragic retrenchment into errors that should have been repented of, not institutionalized. They would also disagree about the amount of continuity and discontinuity there was between the Roman Church before and after the crucial period.

Luther and the churches that developed out of his work really were trying to reform the existing church. In fact, you can picture Lutherans as a group of aggrieved Catholics, pounding on the door of the Roman Catholic church and yelling, “You open these doors and let us back in, we’re not half done reforming you!” Indeed, it’s hard to see why Rome didn’t just start a special Lutheran order of monks to carry out reform: Francis of Assisi had lodged a pretty radical protest against abuses in his time.

John Calvin, for his part, took the only consistent stance possible, and argued that he and his people did not leave the Roman church: that church left the Bible, and the Reformed were standing right there where the Bible had always been, waving goodbye to the Romans and their deviations. Calvin’s response to the Council of Trent was to say that it wasn’t really an ecumenical council, it was an Italian council, since the Protestants and the Eastern churches weren’t invited. He also argued at great length that the great tradition was in essence on the side of sola scriptura and sola fide, citing church fathers voluminously to argue that Rome had deviated from that line only relatively recently. Calvin, in other words, would prefer the diagram that shows one central stream with a small spur, but the central stream would be labeled “Biblical Christianity,” with a little Catholic spur deviating from it and heading off in its own direction as the Roman Catholic denomination. There’s something to be said for that account. But at the very least, the vigor, clarity, and consolidation of Tridentine Catholicism gives it a recognizable profile that is distinguishable from the great Christian tradition at large.