A few years ago I was looking for paintings to use as background images for a lecture. I wanted some biblical imagery that featured scenery over characters, added some beauty and atmosphere without taking over, and was all by one artist so that there weren’t jarring shifts of style. I figured I’d probably end up going with the inevitable Rembrandt, but was also hoping to find something a little less obtrusive (Rembrandt can’t hold back very long from dazzling the viewer).

A few years ago I was looking for paintings to use as background images for a lecture. I wanted some biblical imagery that featured scenery over characters, added some beauty and atmosphere without taking over, and was all by one artist so that there weren’t jarring shifts of style. I figured I’d probably end up going with the inevitable Rembrandt, but was also hoping to find something a little less obtrusive (Rembrandt can’t hold back very long from dazzling the viewer).

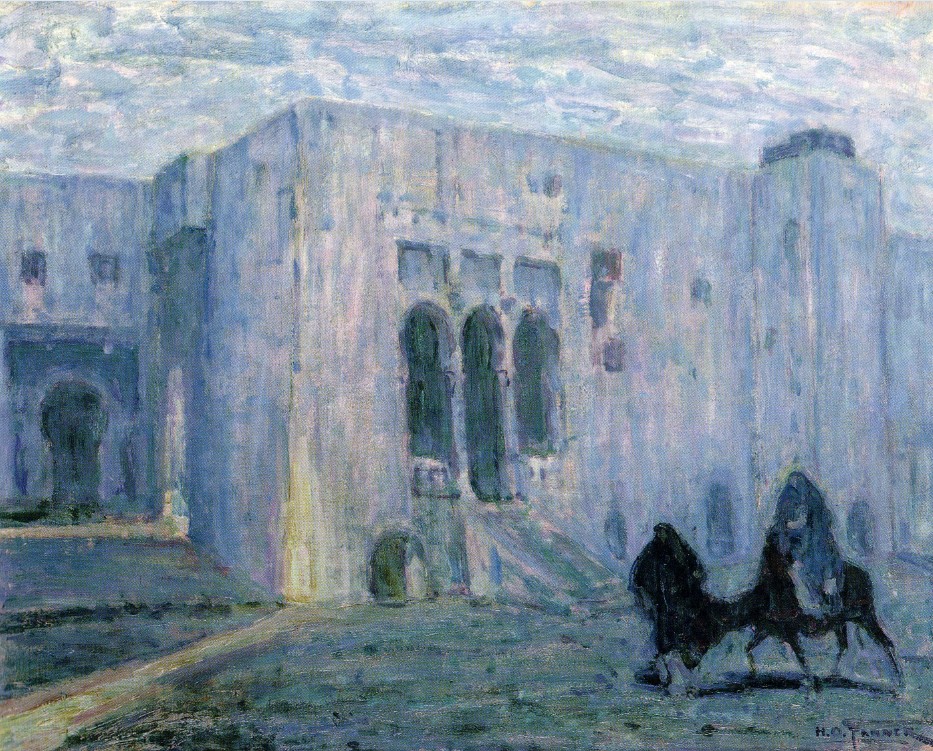

What I found was Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), and in particular his many paintings of biblical scenes. They are a wonderful achievement and well worth getting to know. Tanner traveled to the Middle East to understand the countryside, customs, and settings that would lend verisimilitude to his biblical paintings. He wanted the right kind of people in his paintings: skin tones and physiognomies that would conjure the world of Jesus. Tanner had a sharp eye for the details of everyday life, which I think preserved his biblical paintings from veering too far into exoticism or Orientalism.

Tanner traveled to the Middle East to understand the countryside, customs, and settings that would lend verisimilitude to his biblical paintings. He wanted the right kind of people in his paintings: skin tones and physiognomies that would conjure the world of Jesus. Tanner had a sharp eye for the details of everyday life, which I think preserved his biblical paintings from veering too far into exoticism or Orientalism.

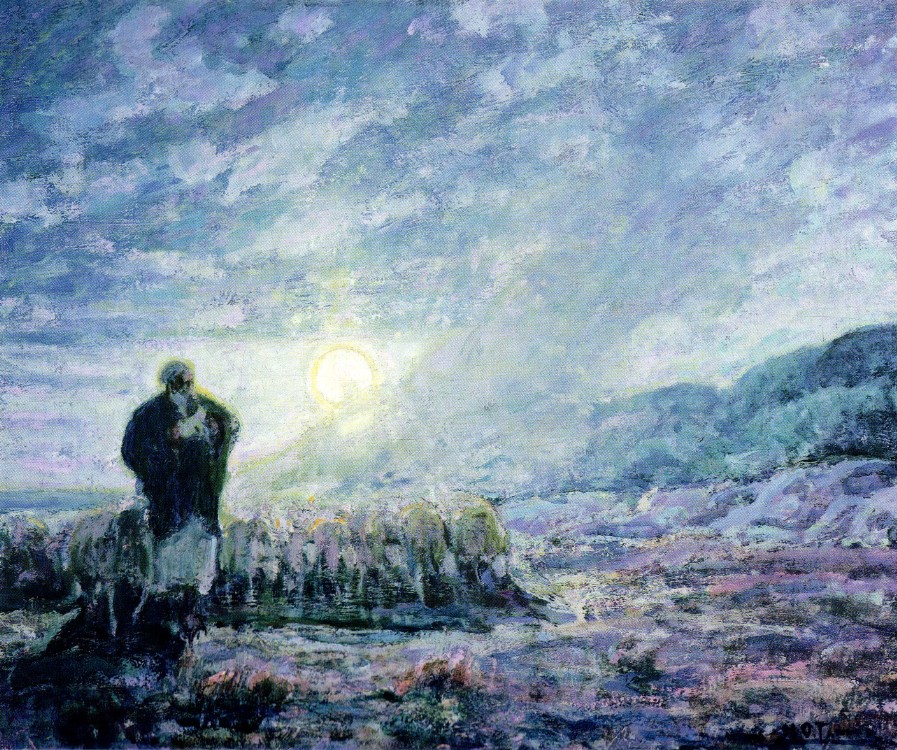

But above all, Henry Ossawa Tanner was a student of the quality and character of light. After spending some time with his biblical paintings, I began to notice that what held them together was a particular presence light that affected all the colors and much of the paint handling. I think this must have been what drew him to take his study trips to the Middle East. All around Palestine and North Africa, Tanner seems to have been on the hunt for a unifying, restrained glow that is almost palpable.

But above all, Henry Ossawa Tanner was a student of the quality and character of light. After spending some time with his biblical paintings, I began to notice that what held them together was a particular presence light that affected all the colors and much of the paint handling. I think this must have been what drew him to take his study trips to the Middle East. All around Palestine and North Africa, Tanner seems to have been on the hunt for a unifying, restrained glow that is almost palpable.

I know you could say almost the same thing about any number of painters –they’re all into light, duh– and that I’m not doing a good job describing it. Here’s Tanner’s own attempt at saying what he was up to:

Remember that light can be many things; light for illuminating an object or for creating a mood; for purposes of dramatization as in a theatrical production. For myself, I see light chiefly as a means of achieving a luminosity, a luminosity not consisting of various light-colors, but a luminosity within a limited color range, say, a blue or blue-green. There should be a glow, which indeed consumes the theme or subject. Still, a light-glow which rises and falls in intensity as it moves through the painting. It isn’t simple to put into words.

This is from Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Spiritual Biography by Marcus Bruce (p. 128). Bruce’s book is not the best place to get an introduction to Tanner –that would be the recent book Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. But Bruce’s book does go out of its way to get at the religious impulse behind Tanner’s work.

Bruce notes that “Tanner was frequently bothered by the quick judgments people were inclined to make about his life and work. Because he was a painter of African descent, journalists focused on that feature as the most important aspect of his work. Because his father was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church it was assumed that he chose to paint religious subjects out of deference to, and respect for, his father. And finally, because he established his reputation as a painter of religious subjects, critics overlooked his experimentation with different styles, techniques, and subject matter.” (p. 14)

Bruce also refers to the character of light as “the most conspicuous and unifying aspect” of Tanner’s work. “It is always a source of goodness,” he says: “It promises not clarity but acceptance and protection; even just touched by it, people are safe.” (p. 121)

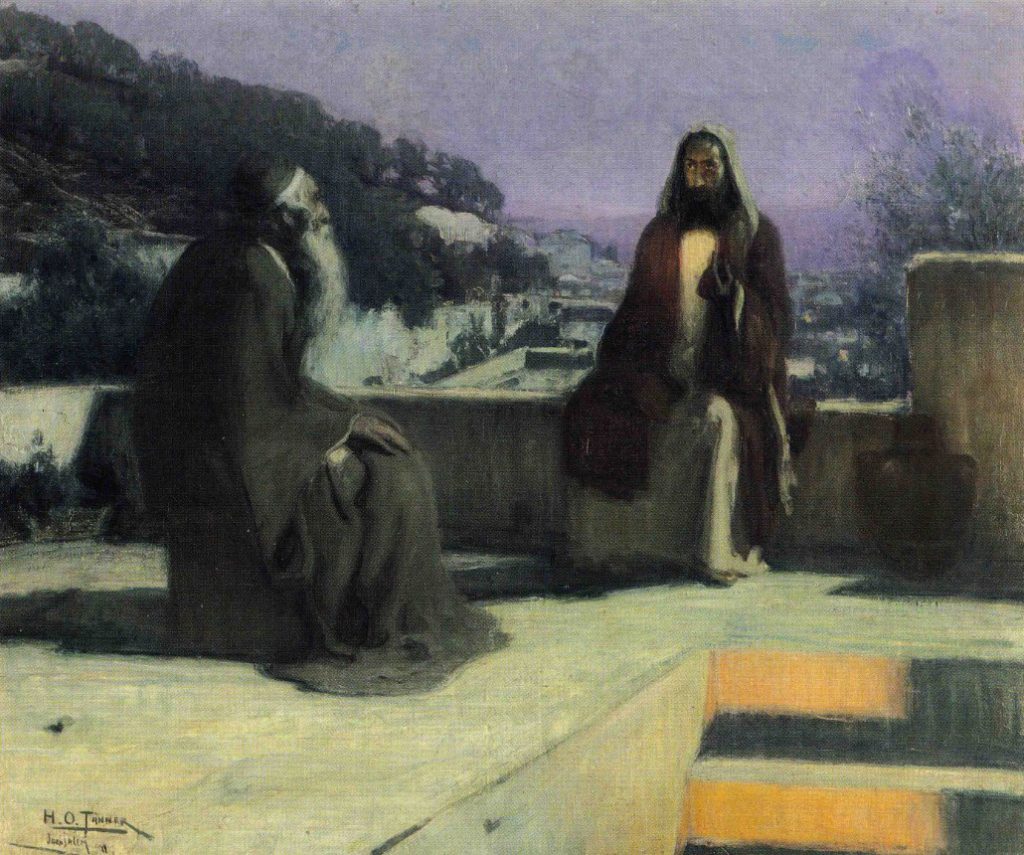

For his biblical paintings, Tanner tended to choose scenes familiar not so much from previous paintings, but from Bible reading or from storytelling. This Nicodemus scene (my favorite Tanner painting) probably suggested itself to him because John 3:2 says Nicodemus came to Jesus “by night,” which presented Tanner with some interesting lighting choices.

If Tanner’s artistic fame begins to climb again in our time, it will probably not be because of spiritual subjects but because he has a pretty good claim to be the first important African American painter to achieve success in salon culture. In fact, he has as good a claim as anyone to being the greatest African American painter, period. He is well located in the canon of African American historical markers. On the one side, his unusual middle name Ossawa, conjures the situation just before the Civil War: it is derived from Osawatamie, Kansas, the site of one of John Brown’s armed battles with pro-slavery forces. On the other side, his artistic importance was debated by no less an African American intellectual than Alain Locke, who wrote of him in 1925,

Our Negro American painter of outstanding success is Henry Ossawa Tanner. His career is a case in point. Though a professed painter of types, he has devoted his art talent mainly to the portrayal of Jewish Biblical types and subjects, and has never maturely touched the portrayal of the Negro subject. Warrantable enough — for to the individual talent in art one must never dictate– who cna be certain what field the next Negro artist of note will choose to command or whether he will not be a landscapist or a master of still life or of purely decorative painting? But from the point of view of our artistic talent in bulk –it is a different matter. We ought and must have a school of Negro art. And that we have not, explains why the generation of Negro artists succeeding Mr. Tanner had only the inspiration of his great success to fire their ambitions, but not the guidance of a distinctive tradition to focus and direct their talents.

Last month I got to see my first Truly Large painting by Tanner in person: the yellow Annunciation in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

I’m not a fan of the psychological intensity of the piece, and I’ve never warmed up to the particular way it subverts the long tradition of Annunciation paintings. Tanner was wise, I think, to devote most of his biblical paintings to scenes that did not have long traditions of representation: such scenes allowed him to be radically novel without the pressure of pushing against received conventions. Taking on the Annunciation means taking on the Byzantine icon tradition, and Giotto, and Fra Angelico, and everybody else. The symbol system is wonderfully precise for this scene, and Tanner’s innovations have always struck me as ill-considered in this piece. I seriously doubt he meant his version to be rapey, but nobody can rescue his painting from interpreters who see it that way. I blame the interpreters mostly, but I think Tanner invited confusion by tweaking the ancient iconographic canons.

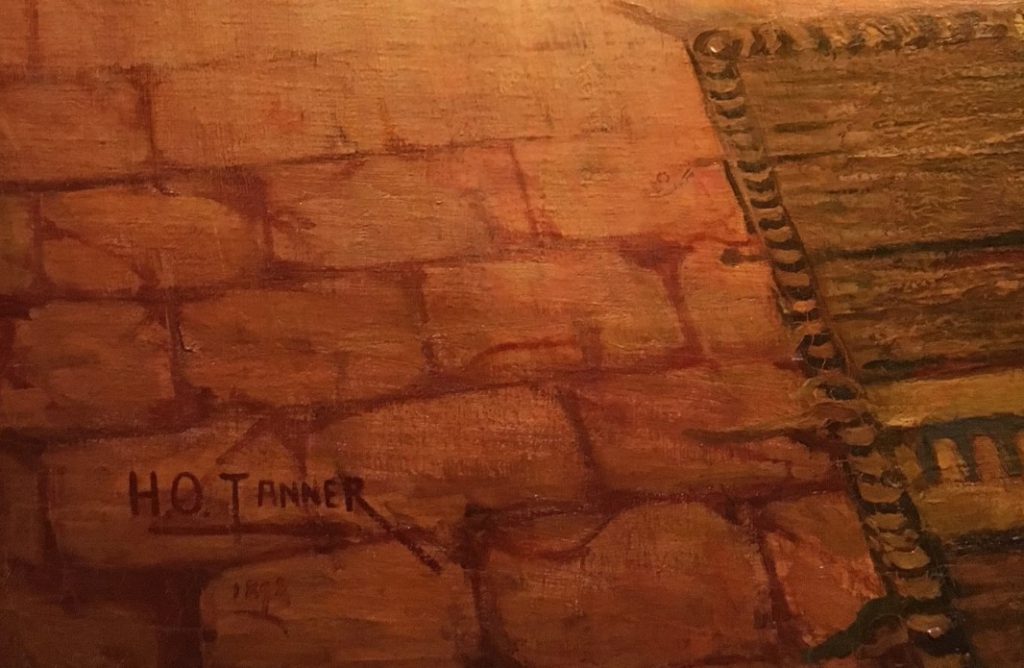

Nevertheless in person and up close, this big yellow painting won me over. Depicting the angel Gabriel as a thin blade of flame gives Tanner a uniquely powerful light source. And in a couple of ways, the realism of the painting is increasingly warped and twisted the closer it gets to the gravitational field of that solar flare: look at the impossibly forced perspective of the swiftly-tilting floor in the signature corner:

That’s not how floors work! Except, apparently, in the presence of the angel.

Or consider how a vase on a shelf just behind Gabriel is transfigured into a study of yellow on yellow on yellow on yellow on yellow, more obviously made of brushstrokes than anything else on the canvas:

And the weirdest part of the picture, the pile of blankets at the foot of Mary’s bed:

Out of context, it would be hard to identify these oleaginous landscape blobs as anything in the textile family.

I’m eager to see my next Henry Ossawa Tanner painting in person. In the meantime, I’ll continue to use his biblical paintings to enrich my experience of the biblical world. If you haven’t looked at Tanner’s work, consider this a strong recommendation.

Sodom and Gomorrha

Returning from the Crucifixion

The Good Shepherd