The Spanish Reformation deserves a lot more attention than it has received; it is a subject almost completely absent from the popular mind. If you want to speak about it, or blog about it like I’m doing right now, you pretty much have to start by announcing to your audience that there was such a thing. Then you can start describing what kind of thing it was.

The Spanish Reformation deserves a lot more attention than it has received; it is a subject almost completely absent from the popular mind. If you want to speak about it, or blog about it like I’m doing right now, you pretty much have to start by announcing to your audience that there was such a thing. Then you can start describing what kind of thing it was.

It was a remarkable thing. Never mind that it was as cruelly crushed out by European political realities as was the Italian Reformation; it nevertheless has a little bit of everything you’d expect from a Reformation movement, and some peculiar special features as well. The Spanish Reformation has roots in Erasmian humanism, with its return to the Bible in the original languages; it expressed itself in vernacular translations straight from Hebrew and Greek into Spanish; it began to work its way out as a revival movement inside of state churches; it spread its influence through neighboring countries when oppression forced it into flight; and it found its doctrinal voice in properly Protestant scholastic theology. But from its vantage point in Spain, it also had a unique relation to its late medieval precursors, a distinctive approach to monasticism and the religious education of the laity, and perhaps a way of integrating personal spiritual experience into the received faith. There are stories to tell here!

This year at Biola, my colleague Octavio Esqueda and I are starting the Spanish Reformers Reading Group, which might just be a fancy name for Octavio and me getting together for coffee after agreeing to read one of the key works of the movement over the next few years. But if you’re in the area and motivated to do the reading, drop me a note and let me know; I may disclose unto you our secret location.

We’re starting with a wonderful little work called the Alfabeto Christiano by Juan de Valdés (c.1509-1541). [Make your Colombian coffee joke here and then meet me in the next paragraph.]

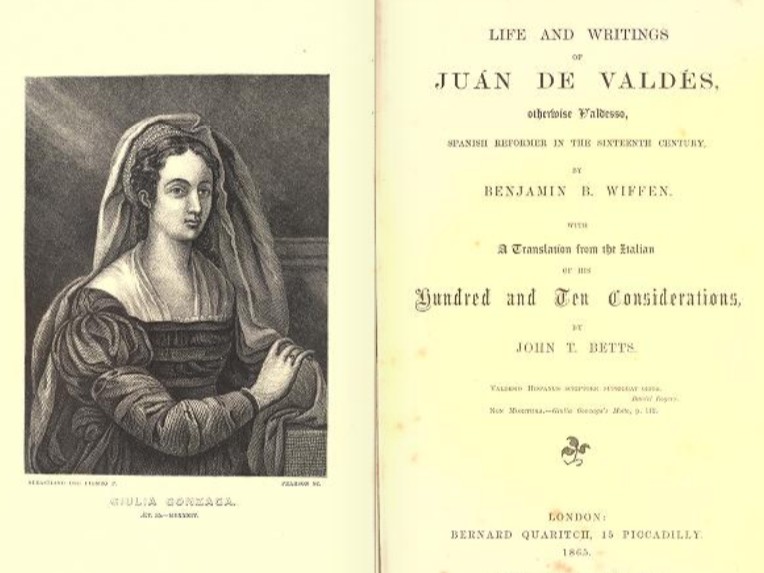

Alfabeto Christiano was written in 1536. It is in dialogue form; in fact it is Valdés’ attempt to transcribe an actual conversation of spiritual counsel that he had with the noblewoman Giulia Gonzaga. Giulia’s voice leads out in the dialogue, as she asks Valdés to help her in her spiritual distress. She has come under the influence of good, gospel preaching, and it has begun to hammer on her conscience and leave her without rest. Valdés explains to her what is happening in her heart: the word of God is coming to her through the preacher’s sermons as law, but that same word is urging her to receive it as gospel. In running dialogue with Gonzaga, Valdés explains the law/gospel distinction (so far so Lutheran), and why her soul is restless until it is renewed in the image of its creator (so far so Augustinian).

Giulia Gonzaga speaks much less than Juan de Valdés in the Alfabeto, but she is hardly reduced to a “Yes, Socrates” role. Her questions and interruptions guide the flow of thought, as Valdés struggles to be clear and non-technical, and also to make sure he is being understood as describing the kind of truth that requires a transformed way of life rather than just inert theological notions to be catalogued mentally. This conversation is not about fixing a few ideas, but about the content of the word of God changing a life. He calls it an alphabet because he is going over the basic principles of the gospel and the life in Christ.

Valdés speaks much of Christian perfection, and sees no conflict between that and his absolute insistence on justification by faith –the latter being probably his chief doctrinal emphasis in all his works, and certainly what got him in the most trouble with the Inquisition. He also speaks much of “reading in your own book,” by which he means attending to what is happening in your own soul, and he speaks of the inner illumination of the Holy Spirit –in fact, the reason we have Valdés’ works in English is partly because Quakers appreciated his way of speaking.

By the way, check out the works of Juan de Valdés here.

I warmly commend the Alfabeto Christiano as a neglected classic of Protestant theology and spirituality, and encourage you to recover it from obscurity if you have any interest in these matters. The nineteenth-century English translation is public domain and available online; here is a link to the pdf we’re reading (it’s just the google books scan, minus the voluminous front and back matter).