Today (April 4) is the day when Ambrose of Milan died in 397. Ambrose is one of the biggest names in the history of the early church, one of the traditional “Four Doctors of the Western Church.” He was the bishop of Milan when Augustine came there, and he made a big impression on Augustine. One of the things Augustine noticed about him was that when he read books, he did not read them out loud to himself, as was the custom at that time. Instead:

Today (April 4) is the day when Ambrose of Milan died in 397. Ambrose is one of the biggest names in the history of the early church, one of the traditional “Four Doctors of the Western Church.” He was the bishop of Milan when Augustine came there, and he made a big impression on Augustine. One of the things Augustine noticed about him was that when he read books, he did not read them out loud to himself, as was the custom at that time. Instead:

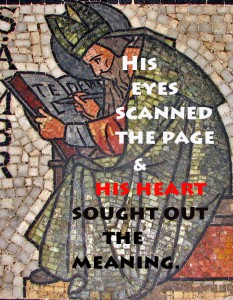

When he read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud.

Augustine mentioned it because it was an unusual reading practice at the time. But you can tell from the way he describes it that it struck him as an almost mystical thing. The man took information from the page and put it into his own mind without any outward sound or motion: “his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning.”

Of course there was a lot more to Ambrose of Milan than just silent reading tricks. He did in fact take Scripture into his heart and meditate on it profoundly. Of his surviving writings, his short exposition of The Christian Faith is probably his masterpiece. He wrote it at the request of Gratian, the emperor of the West, who was heading East and wanted a refresher course on Christian truth lest he come under the influence of the Arianism that was rampant in the eastern territories. Not many systematic theology treatises are written with such geopolitical pressure on them. And Ambrose’s life as the bishop of an important city was filled with political tensions. He called one Emperor to repentance for mass murder, and forced another one to back down from his demands that Arianism be treated as an authentic version of Christianity. Short of taking the reins of political power himself, Ambrose had maximum influence on imperial policies. Some of Ambrose’s most extensive writings are about the strict rules of conduct to be observed by Christian leaders.

For us, the fame of Augustine eclipsed that of Ambrose (except in Milan, a secular city that is still proud of their great bishop). But as Augustine makes clear in his Confessions, he looked up to Ambrose as a Christian leader who was unapproachably great. Ambrose preached with authority, interpreted the Bible powerfully, and had the pastoral insight to know that Augustine’s mother was almost too religious, verging on superstitious. When Augustine asked what book of the Bible he should read, Ambrose suggested Isaiah. Augustine tried his best to understand it, but had to admit defeat. Aristotle he understood, but Isaiah beat him back. Augustine settled for close study of the Psalms, and prayed that he could someday return to Isaiah and try to measure up to the understanding of Ambrose.