What is this beautiful thing?

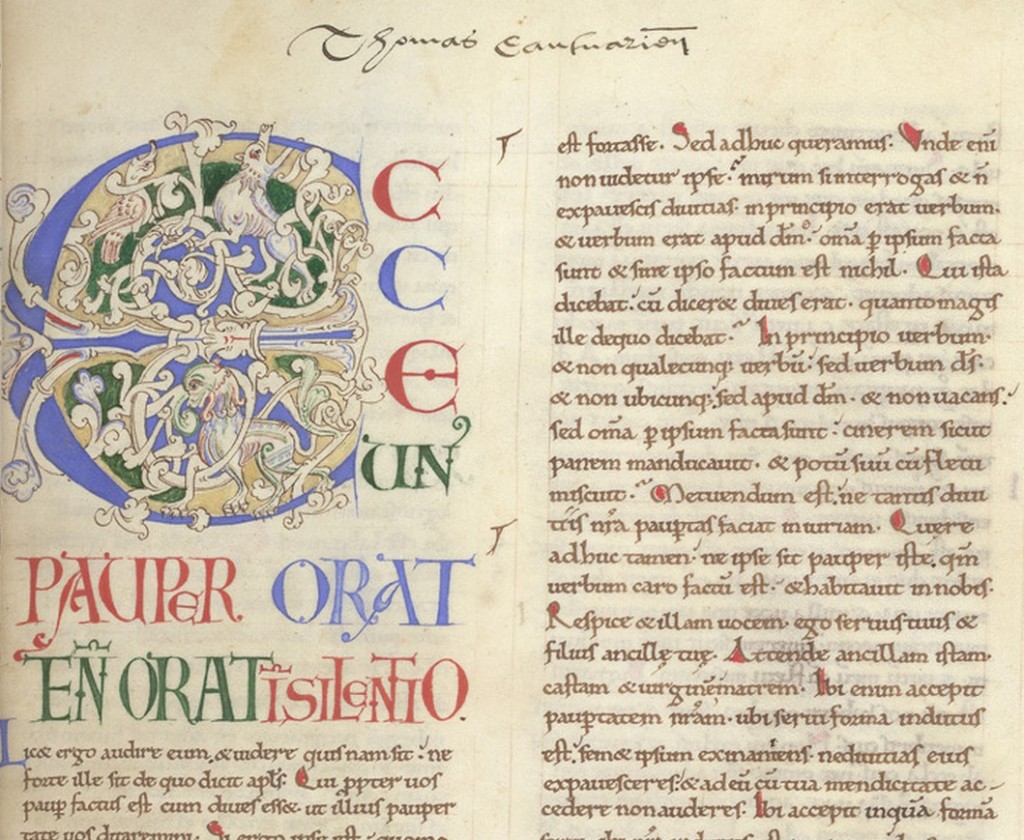

It’s Augustine’s commentary on Psalm 102. He composed it in the fifth century, but this is a Carolingian copy that was written out in the twelfth century, owned by Thomas Cranmer in the sixteenth century (behold his signature at the top center), housed in the British Library since the eighteenth century, and now viewable online at their website via twenty-first century technology.

It’s Augustine’s commentary on Psalm 102. He composed it in the fifth century, but this is a Carolingian copy that was written out in the twelfth century, owned by Thomas Cranmer in the sixteenth century (behold his signature at the top center), housed in the British Library since the eighteenth century, and now viewable online at their website via twenty-first century technology.

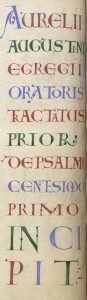

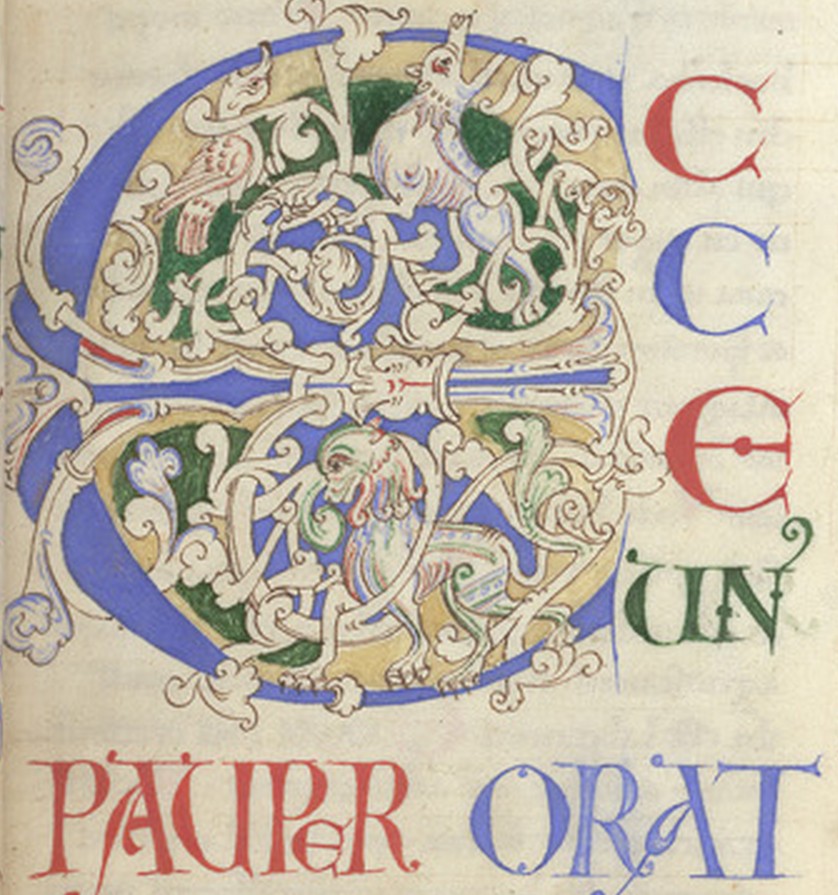

This must be from a three-volume set, because this volume begins with Psalm 102 (or as Augustine and the Vulgate would have it, Psalm 101) and has all sorts of multi-color introductory decoration (see sidebar to the left here) and a great big decorated capital. It’s a giant letter E, containing floral decor, vine patterns, and at least three animals. I think that’s a lion, a dog, and a bird, and the dog, at least, looks letter-chomping mad.

You can read Psalm 102 here; its ancient superscription calls it “a prayer of one afflicted, when he is faint and pours out his complaint before the Lord,” and its opening line is “Hear my prayer, O Lord; let my cry come to you!”

You can read Psalm 102 here; its ancient superscription calls it “a prayer of one afflicted, when he is faint and pours out his complaint before the Lord,” and its opening line is “Hear my prayer, O Lord; let my cry come to you!”

You can read Augustine’s commentary here; and the original Latin of it here (so you can make out all the letters in the manuscript: ECCE UN[us] PAUPER ORAT).

It’s safe to say that in his exposition of this Psalm, Augustine makes a beeline for Jesus. Typical (get it?).

His commentary begins, “Behold, one poor man prays, and prays not in silence. We may therefore hear him, and see who he is.” Overhearing the one who prays, we can guess at his identity as he puts himself into his prayer.

“Perchance,” says Augustine, it may be “He, of whom the Apostle says, Though He was rich, yet for your sakes He became poor, that you through His poverty might be rich (2 Cor 8:9).” And from there, Augustine is off into a meditation on the richness of the divine life that the Son shares with the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit; the poverty into which the human race fell through sin; and the glorious exchange by which the former cured the latter.

It may seem like a strange starting place for a Psalm commentary, and it’s probably healthy for us to acknowledge that the New Testament things Augustine finds in this Old Testament text are not there verbatim in the historical-grammatical sense. He is instead performing a kind of holistic canonical synthesis, bringing the entire meaning of Scripture to bear on the particular words of this Psalm. What’s delightful and perhaps surprising is how helpful that move is, not just for changing the subject to Jesus, but for seeing more deeply into the Psalm itself, especially its oddities of phraseology, its juxtapositions of imagery, and its intuitive leaps.

Because the Psalm says “let these things be written for those that come after,” Augustine reads “from one generation to another” as a reference to the main divisions of salvation history: “‘In our generation’ belongs to the Old Testament; while ‘in the other generation’ belongs to the new.”

And don’t miss what he says about the bird life: “Behold three birds and three places: the pelican, the owl, and the sparrow.”

In fact, go ahead and read it all. The pretty picture was just to catch your eye.