Jesus is God, but did he know during his earthly ministry that he was God? Was he, as a human, aware of his divinity? I think it is necessary, for biblical and logical reasons, to answer yes to this question, but I freely admit that doing so raises further difficult questions and forces us to affirm an incarnation of the Word that staggers the imagination.

Jesus is God, but did he know during his earthly ministry that he was God? Was he, as a human, aware of his divinity? I think it is necessary, for biblical and logical reasons, to answer yes to this question, but I freely admit that doing so raises further difficult questions and forces us to affirm an incarnation of the Word that staggers the imagination.

How could somebody live a recognizably human life, and think genuinely human thoughts, while consciously entertaining the awareness that he is God? Deity doesn’t always drive out humanity, but in the realm of consciousness it is hard to account for how the two thoughts “I am human” and “I am God” could coexist. I doubt it’s a demonstrated contradiction of the hard, logical “square circle” variety, but the two ideas do seem to clash.

To avoid the clash of ideas, some Christian thinkers have sought refuge by putting the deity and humanity of Christ at the level of being, but keeping it out of his awareness: He was God and man, but he didn’t know he was God and man. Jesus didn’t theologize about his two natures —that’s our job— because he was busy doing the more important thing, being the mediator between God and man in those two natures.

I think this attempted solution is inadequate. But before rejecting it, I want to understand it thoroughly and see if anything can be scavenged from it for more constructive uses.

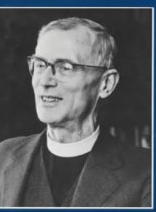

Austin Farrer (1904-1968) was an Anglican theologian whose claim to fame may be his friendship with C. S. Lewis. In a lecture called Very God and Very Man” (published in his book Interpretation and Belief, but also available in the recent anthology Truth Seeking Heart), he took up the question of Christ’s consciousness of his Godhood. Farrer always wrote with luminous clarity, so I’ll let him explain himself:

I want to apply Ryle’s famous distinction between knowing how and knowing that to the mystery of the incarnate consciousness. … an omniscient being who knows all the answers before he thinks and all the future before he acts is not a man at all, he has escaped the human predicament. … On the other hand, he knows how to be the Son of God in the several situations of his gradually unfolding destiny, and in the way appropriate to each. He is tempted to depart from that knowledge, but he resists the temptation. And that suffices for the incarnation to be real. For ‘being the Son of God’ is the exercise of a sort of life; and in order to exercise it he must know how to exercise that life: it is a question of practical knowledge. A theoretical knowledge about the nature of the life he lives is unnecessary, it suffices that he should live it. “I would rather know how to repent than know the definition of repentance” is an ancient saying: and it was enough for Jesus to exercise the personal existence of the Second Person in the Trinity: he might leave to schoolman the definition of the Trinity, especially in view of the fact that it cannot be verbally defined.

Jesus, according to Farrer’s argument, knew how to be God, but did not know that he was God. The horizon of his consciousness was filled with the ideas of a human consciousness, but his wisdom, his practical approach to life, and his skill in doing the right thing were all coming from the untheorized fact of his divinity. He had know-how, but not knowledge-that.

This picture of Christ is unacceptable for two reasons: First, it doesn’t adequately match the way Jesus taught; or rather it can only be squared with the gospels if you decide that the evangelists are putting their own theologies on the lips of Jesus rather than accurately presenting the theology of Jesus himself. Second, the distinction between knowing-how and knowing-that is a meaningful distinction, but it’s not the kind of sharp dichotomy you would need to keep all that knowing-that-I’m-God hermetically sealed from the knowing-how-to-be-God. Know-how, it seems, either bleeds over into know-that, or presupposes some know-that. I’m not the first to point out either of these objections, either in biblical studies or in philosophy of mind. Farrer was an accomplished scholar in both disciplines, but I think in this argument he makes errors in both fields at once. And I won’t say more about them here, because I’m still interested in scavenging something useful from Farrer’s argument.

I would like to keep what Farrer affirms, but reject his denial. It is worth pondering Jesus’ know-how at greater length. Farrer may have been driven to focus on Jesus’ know-how because he wrongly felt he had to reject Jesus’ know-that, but the happy result is that he arrived at some great insights about Jesus’ practical wisdom in living out a divine life in a human nature.

Turn your mind for a moment away from the question “what was it like to know, humanly, that he was God.” Instead, think for a moment about the question “what was it like to know how to behave as the Son of God at every moment of a human life?” Notice that to put the question well, I had to insert the idea of divine sonship: now “how was Jesus God,” but “how was Jesus the Son of God?” Of course I mean “Son of God” in the full trinitarian sense: the eternal second person of the Trinity, who is fully God, and without whom the Father has never been. This is who Jesus is: not God the Father, not God in general, not God the Trinity, but God the Son, one of the Trinity. This is who the man Jesus Christ knew how to be.

Austin Farrer is better than anyone else I’ve read at making this point: Jesus was the Son of God, and knew how to be the Son. Here is the great golden passage from Farrer’s sermon on “Incarnation” where he states the case so well:

We cannot understand Jesus as simply the God-who-was-man. We have left out an essential factor, the sonship. Jesus is not simply God manifest as man; he is the divine Son coming in manhood. What was expressed in human terms here below was not bare deity; it was divine sonship. God cannot live an identically godlike life in eternity and in a human story. But the divine Son can make an identical response to his Father, whether in the love of the blessed Trinity or in the fulfilment of an earthly ministry. All the conditions of action are different on the two levels; the filial response is one. Above, the appropriate response is a co-operation in sovereignty and an interchange of eternal joys. Then the Son gives back to the Father all that the Father is. Below, in the incarnate life, the appropriate response is an obedience to inspiration, a waiting for direction, an acceptance of suffering, a rectitude of choice, a resistance to temptation, a willingness to die. For such things are the stuff of our existence; and it was in this very stuff that Christ worked out the theme of heavenly sonship, proving himself on earth the very thing he was in heaven; that is, a continuous perfect act of filial love.

Austin Farrer, “Incarnation,” (sermon preached in Keble College Chapel, Oxford 1961), in The Brink of Mystery, edited by Charles C. Conti (London: SPCK, 1976), p. 20.

That is the way forward for better thinking about the incarnation: to keep it properly situated in trinitarian perspective. Jesus was the Son, and lived that life of sonship on earth as he did in heaven. Take this truth and make it your own however you can: ponder it, pray it, re-read the gospels with it in mind. You will find it to be a truth that keeps giving off more light, illuminating things you’ve always known but haven’t considered thoroughly.

As for the denials that drove Austin Farrer to this insight, they are unfortunate. A certain kind of critical scholarship was at its high-water mark in the middle of the twentieth century, and books like The Myth of God Incarnate were widely considered to be the state of the art, or the best we could do if we wanted to be critical thinkers who had some sort of faith in Jesus. Farrer was on the side of the angels in that conflict, and did a lot to help recover a firmer Christian faith. But even his best arguments bear some of the marks of the conflict with hard-core liberalism, especially in his denomination.

One good reason to get clear about this is that some of Farrer’s best insights also show up in N. T. Wright’s influential work. See how he develops the argument in his short book The Challenge of Jesus (at p. 122):

I do not think Jesus “knew he was God” in the same sense that one knows one is hungry, or thirsty, tall or short. . . . It was more like the knowledge that I have that I am loved by my family and closest friends; like the knowledge that I have that sunrise over the sea is awesome and beautiful; like the knowledge of the musician not only of what the composer intended but of how precisely to perform the piece in exactly that way-a knowledge most securely possessed, of course, when the performer is also the composer. It was, in short, the knowledge that characterizes vocation.

Wright has a lot in common with Farrer. You can see his argument follow the same track, know-that vs. know-how, and a compelling case for the significance of the know-how. In Wright’s case, he develops the theme of Jesus’ know-how in biblical terms of “vocation” in a way that is well worth reading. Wright and Farrer also have this in common: They are both large-minded Anglican theologians who want to serve the church of Jesus Christ, whose affirmations are exciting and whose denials are perplexing.