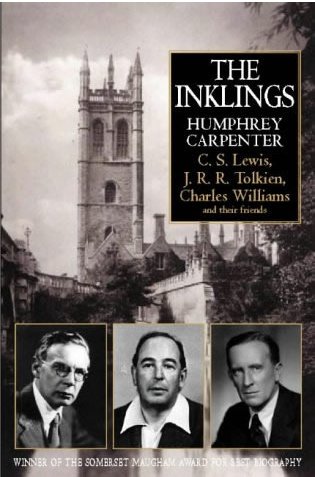

It’s hard to account for just how much influence continues to stream from that little group of writers called the Inklings. Never mind that the works of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien have survived into the twenty-first century in the unlikely form of Hollywood blockbusters trailing cash and merchandise as far as the eye can see. The most influential of the Inklings were Lewis, Tolkien, and Williams, and their power of influence can be stated this way: they communicated versions of Christianity that proved interesting to the modern mind.

It’s hard to account for just how much influence continues to stream from that little group of writers called the Inklings. Never mind that the works of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien have survived into the twenty-first century in the unlikely form of Hollywood blockbusters trailing cash and merchandise as far as the eye can see. The most influential of the Inklings were Lewis, Tolkien, and Williams, and their power of influence can be stated this way: they communicated versions of Christianity that proved interesting to the modern mind.

They were serious about their religion in a time and place where that was not encouraged. In Oxford in the early 20th century, you could either be a raving fanatic Methodist type, or you could be one of those contemptible clergymen of the type Jane Austen ridiculed so effectively. Neither option was acceptable to the Inklings, so each of them drew on their powers of imagination to project a Christian faith that had the power to fascinate people and commend itself as worth taking seriously. Each of the big three found their own approach: Christianity as saga, as fairy tale, as ghost story.

J. R. R. Tolkien‘s thought was, “What if you treated Christianity as if it were a sprawling saga?” And the next thing you know, Tolkien’s imagination had not only created a whole fully-articulated sub-creation, filled with characters of mythic proportion put in place by inconceivably long and complex lines of development, but had also ennobled the real world we live in together. Immerse yourself in Tolkien’s middle earth and you find the moral colorings of your own world more vivid, the stakes of the game higher, history more pregnant with meaning, and the flat sky overhead giving way to heavens over heavens over heavens, infinite miles below a distant Illúvatar who framed the worlds in song. Christianity’s not a sprawling epic, exactly, but the association brings out things that need to be noted.

C. S. Lewis‘ bright idea was, “What if Christianity were a fairy tale?” And he worked out the basic idea in the Chronicles of Narnia, where adventures can happen under the watchful eye of a divine Lion. In his non-fiction work, he was very careful with the notion of fairy tale, insisting that Christianity tells the fairy story that is true, the myth that became fact without losing any of its world-defining power as myth. But the Narnian ethos informs everything about his way of being Christian. For Lewis, even the presence of Christians in the world –certainly the presence of conspicuously saintly ones– is almost like the presence of the fairy folk among us: “Every now and then one meets them. Their very voices and faces are different from ours; stronger, quieter, happier, more radiant. They begin where most of us leave off. They are, I say, recognisable; but you must know what to look for.” Being holy, Lewis says, “is rather like joining a secret society.” “It must be great fun,” he concludes, putting the finishing touch on a kind of Christianity that begins “once upon a time,” ends “happily ever after,” and in the in between time, under the mercy, is as tough-minded as it is tender-hearted.

Charles Williams‘ scheme was, “What if Christianity were a bizarre secret cult?” And the more he described it, the more it began to seem like one, with the walls of the church dissolving around a mysterious brotherhood of Sharers in the Coinherence, gathering to bind themselves with terrible oaths of loyalty to their Dead Master who haunts them still. John Mark Reynolds recently offered as good a defense and recommendation of Williams as can reasonably be expected from a normal mind. Williams didn’t have a normal mind, but it would be cheap to dismiss him as abnormal. He was paranormal to the core, and he described a kind of Christianity that feels haunted and deep, conspiratorial and ineffable. Mostly it gives me the creeps and seems affected. If the current trend of taking Inklings to Hollywood continues, we can expect some incredibly spooky adaptations of Williams novels (Scott Derickson, clear your schedule).

No decent person wants to be a Jane Austen clergyman. So Tolkien imagined Christianity as a saga, Lewis imagined it as a fairy tale, and Williams imagined it as a ghost story. They didn’t make the classic liberal mistake of re-tooling Christianity to fit whatever was currently popular. But they made it not boring, and that drew attention, and that has produced great and lasting results.