I just got a copy of the new Ancient-Modern Bible from Thomas Nelson. It’s a kind of study Bible with running commentary in the margins drawn from the whole history of the church, and several dozen biographies introducing some of the historical commentators. It also has a section of Christian art, and a number of articles on Christian doctrine. The translation is NKJV, the page size is compact, but the book is pretty thick and heavy. Hardcover, comes in a box, has a couple of page-marker ribbons. Give it a look.

I just got a copy of the new Ancient-Modern Bible from Thomas Nelson. It’s a kind of study Bible with running commentary in the margins drawn from the whole history of the church, and several dozen biographies introducing some of the historical commentators. It also has a section of Christian art, and a number of articles on Christian doctrine. The translation is NKJV, the page size is compact, but the book is pretty thick and heavy. Hardcover, comes in a box, has a couple of page-marker ribbons. Give it a look.

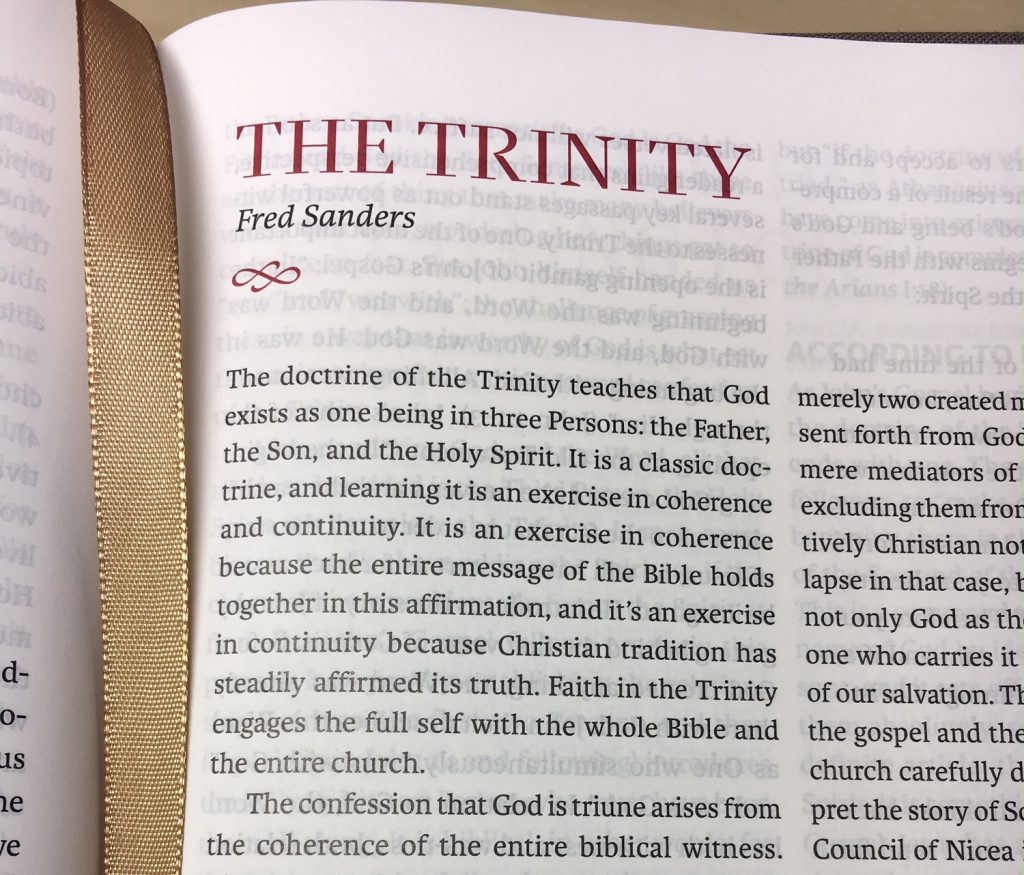

The editors invited me to write the article on the Trinity for this project, which was a challenge (only about 2,000 words?!) and an honor. I approached the article as an opportunity not only to establish the main, plain lines of classical trinitarian doctrine, but to do so in a way that emphasizes how the doctrine contributes to the coherence and continuity of the Christian faith.

Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of the article.

The doctrine of the Trinity…is a classic doctrine, and learning it is an exercise in coherence and continuity. It is an exercise in coherence because the entire message of the Bible holds together in this affirmation, and an exercise in continuity because the entire Christian tradition has steadily affirmed its truth. Faith in the Trinity engages the full self with the whole Bible and the entire church.

The confession that God is triune arises from the coherence of the entire biblical witness. This is good news, since it means the doctrine isn’t just dependent on a few scattered or difficult texts here and there. But it can also pose a challenge, because readers have to be able to take a step back from the details of the Bible in order to ask the most comprehensive questions: What is the point of the entire story, and what does it entail about the God who is its central character? When read from beginning to end, the Bible is the story of salvation accomplished by the Triune God. It begins with the one true God’s revelation of his identity to Israel. This God is the maker of heaven and earth, the God of Abraham, who promises that in the fullness of time he will redeem his people. Through his word and by his spirit, God in the Old Testament promised to send forth his Word and pour out his Spirit. The New Testament completes the story by telling how he did so, in the incarnation and Pentecost. These are the two ways by which God lives among his people.

There have always been attempts to interpret the Son and the Holy Spirit as non-divine, as merely two created messengers among the many sent forth from God. This would treat them as mere mediators of salvation from God, while excluding them from being God. But the distinctively Christian notion of salvation would collapse in that case, because the gospel demands not only God as the agent of our salvation (the one who carries it out) but also as the content of our salvation (“I will be your salvation… I am your reward”). This close connection between the gospel and the Trinity is why the Christian church carefully defined the right way to interpret the story of Scripture, most famously at the Council of Nicaea in 325. The bishops who gathered at Nicaea recognized that reading the Bible as if the Son of God were a created emissary would mean reading the Bible in a way that deflated salvation. Furthermore, if the Son were a mere creature, then the story of the Bible would be torn apart between the testaments. God’s Old Testament promise to save his people by dwelling among them would be left hanging; the subject would have to change to how God sent a creature instead. The same church that recognized the triunity of the biblical God recognized that it took both testaments together to preserve the story in which that God’s triunity was made known. So the Gospel, the Trinity, and the Christian Bible stand together.