In an article in the Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie, T. Mahlmann claims that the first use of the word christology occurs in Friedrich Balduin’s commentary on Paul’s letters. When I ran across this reference in a footnote about something else, I realized (a) I found this to be both a little bit interesting and a little bit surprising, (b) I had a PDF of Balduin’s commentary on my hard drive from some research I did last year, so I could look it up pretty easily, (c) I had nowhere to use this interesting and surprising thing I had learned, and (d) I have a blog I can post to.

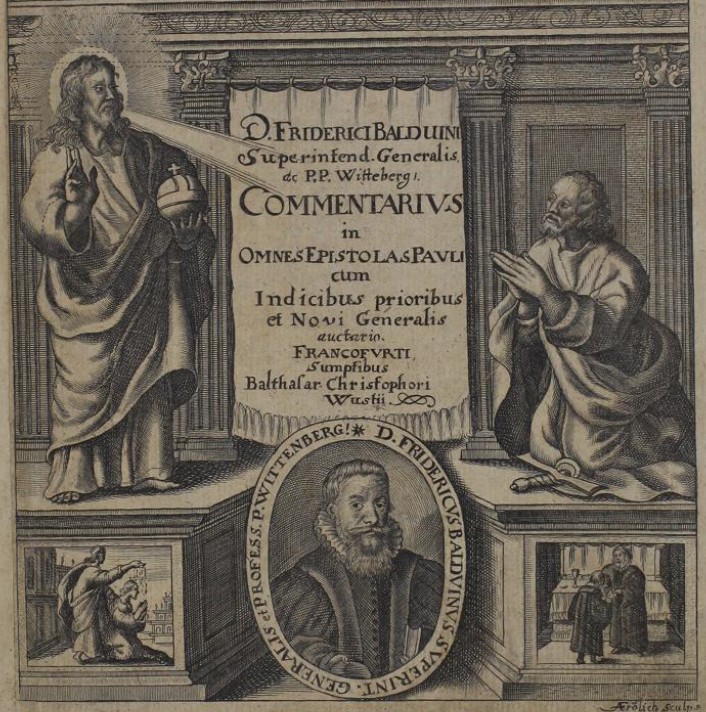

Balduin (1575-1627) wrote a pretty cool commentary with an amazingly awesome frontispiece:

It’s pretty extra, as the kids say, but if I ever write a truly jumbo commentary on all of Paul’s letters, I’m probably going to insist on an impressive frontispiece, too. (I might skip the !* right over my head in my portrait, though.)

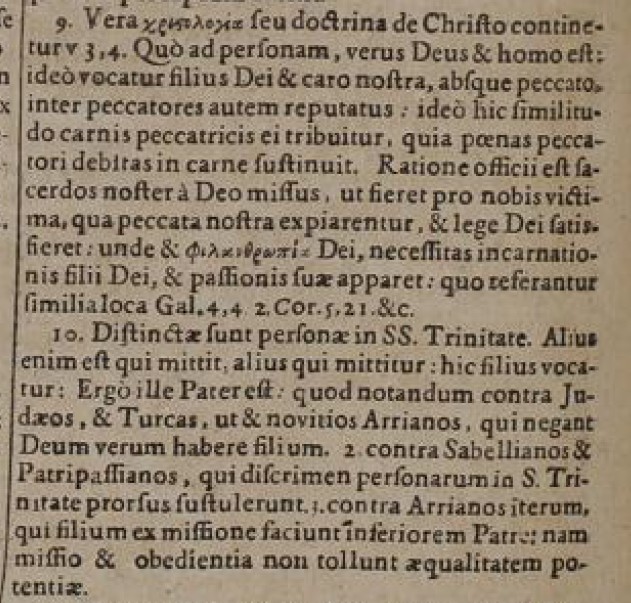

In his commentaries, Balduin first offers a paraphrase of the entire passage, then does the standard running verse-by-verse thing we expect from commentaries. But then he adds a few more layers, rising to a more topical treatment that builds on and complements his running comments. He poses a series of questions that arise from the text, and handles them in dialogue with earlier theologians and confessions. And then he offers a series of “theological aphorisms” on the the section he’s just discussed. It’s in this set of aphorisms on Romans 8:3-4 that he (according to Mahlmann) coins the term christology. It’s right in the first line of aphorism 9:

Romans 8:3-4, says Balduin, contains the true christology, or doctrine of Christ. He then unpacks just how much christology Paul delivers in this teaching that God sent his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and for sin, in order to condemned sin in the flesh. True God, true man; God’s Son, our flesh. He concludes by pointing out significant parallel passages: Gal 4:4, 2 Cor 5:21, etc.

So there you go: Apparently the handy word christology came about when a Lutheran theologian was commenting on Paul.

(Bonus in the picture above: I included aphorism 10, which I think flows nicely from aphorism 9. In the ninth aphorism, Balduin uses classical christology to see into the depths of Paul (see, I couldn’t have said that concisely without Balduin’s coinage); in the tenth, he uses classic trinitarian theology in the same way: You can’t understand Romans 8:3 rightly without recognizing that the persons of the Trinity are distinct: one sends, the other is sent; the sender is the Father, the sent is the Son. This insight also refutes Judaeos, Turcas, Sabellianos et Patripassianos, and two kinds of Arrianos.)