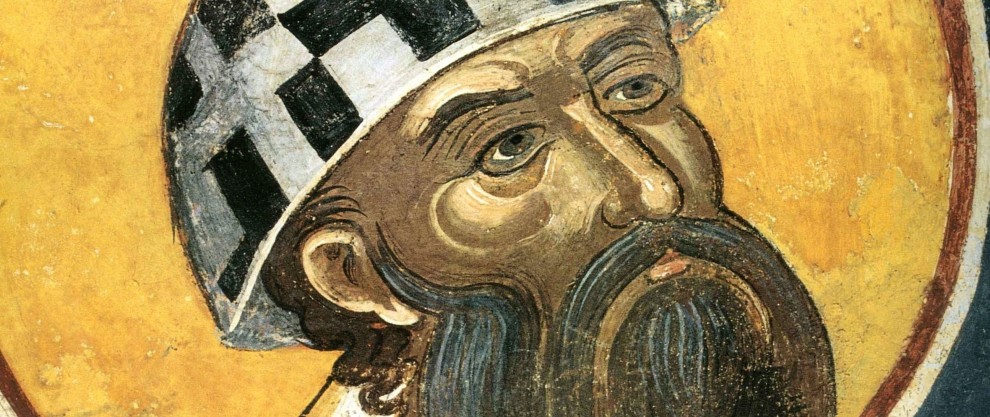

June 27 is the day Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444) is remembered in the Western churches. For many years, he wasn’t widely remembered in the Western churches at all, at least in English-language theological circles. For example, in the 48-volume set of patristic writings of the Ante-Nicene, Nicene, and Post-Nicene periods issued in the nineteenth century, there is no Cyril volume. That means that people getting their first crash course in the church fathers have had to go digging elsewhere to get Cyril in English.

Which is a shame, because Cyril’s theology is profound, his style is forceful, and his influence on the great tradition of Christian doctrine has been immense. He is certainly on my list of ten most important church fathers, and he might be one my top five list. I used to think of him as someone who did a good job carrying out the theology of Athanasius into the fifth century. But now I recognize him as someone who grasped the doctrinal center of the whole christological debate even more firmly than Athanasius. Building on Athanasius’ work, Cyril took the step of thinking through the significance of Jesus being one of the Trinity.

Cyril’s theology was the major influence behind a set of essays I edited in the 2007 book Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective (B&H Academic, 2007). As Klaus Issler and were pulling that volume together, we wanted all the essays to focus on the fact that Jesus Christ is the eternal Son of God, the second person of the Trinity. As we worked that simple central idea out in various ways, I knew I wanted a historical theologian to introduce readers to Cyril of Alexandria. So I wrote to Donald Fairbairn and asked him if he could recap some of the main ideas from his book Grace and Christology in the Early Church. Donald was glad to do so, and produced a very strong essay that everybody ought to read.

Fairbairn’s essay begins by quoting Lionel Wickham’s assertion that “The patristic understanding of the Incarnation owes more to Cyril of Alexandria than to any other individual theologian. The classic picture of Christ the God-man, as it is delineated in the formulae of the Church from the Council of Chalcedon onwards, and as it has been presented to the heart in liturgies and hymns, is the picture Cyril persuaded Christians was the true, the credible, Christ.”

“The Logos Personally Experienced Human Life,” says Fairbairn, as he commends Cyril’s theology for evangelicals:

One of Cyril’s most common ways of referring to the incarnation is to speak of the Logos as uniting flesh (that is, humanity) to his own person, so that the humanity of Christ is the Logos’s own flesh. The word “own” (idios in Greek) then becomes Cyril’s keyword for stressing that the Logos himself is personally present on earth with us through the humanity that he has made his own. His humanity is not a distinct person, but instead a set of properties that the Logos possesses after the incarnation, so that the Logos himself can personally live as a man. Thus one can say unequivocally that God the Logos was born, the Logos suffered, the Logos died on the cross and was raised (all of which statements Theodore and Nestorius refuse to make). I will give three examples of this pattern.

I see that Fairbairn has a book coming out soon in which he takes this central Cyrilline insight and makes it the center of an introduction to theology. I’m looking forward to that. But in the meantime, I can’t resist recommending Jesus in Trinitarian Perspective for Fairbairn’s excellent essay, and several others.