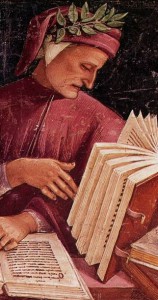

Today (September 14) is the day Dante Alighieri (ca. 1265 – 1321) died. Dante, author of the three-part Divine Comedy, was proud to be Italian: he wrote about the politics of Italy, chronicled his love-hate relationship with Florence, and perhaps most significantly, he wrote his masterpiece in Italian. That was a major decision in the 14th century. It meant very few people outside his region would be able to read the work fluently, but that almost anybody in his region, Latin-trained scholar or not, would be able to. He was an ardent believer in the possibility of eloquence in the common dialect of his people. He even wrote a book about it –in Latin. Within a century or so, everybody would recognize the value of having great writing in a host of vernacular literatures. But in the 1300s, it was geniuses like Dante and Chaucer who could see the way the languages of Europe were heading. When Dante wrote his works, people thought it odd that he would compose such epic poetry in the regional, sub-literary dialect of Tuscany, a local language that didn’t even have a name. But Dante called it Italian, and now we all call it that.

Today (September 14) is the day Dante Alighieri (ca. 1265 – 1321) died. Dante, author of the three-part Divine Comedy, was proud to be Italian: he wrote about the politics of Italy, chronicled his love-hate relationship with Florence, and perhaps most significantly, he wrote his masterpiece in Italian. That was a major decision in the 14th century. It meant very few people outside his region would be able to read the work fluently, but that almost anybody in his region, Latin-trained scholar or not, would be able to. He was an ardent believer in the possibility of eloquence in the common dialect of his people. He even wrote a book about it –in Latin. Within a century or so, everybody would recognize the value of having great writing in a host of vernacular literatures. But in the 1300s, it was geniuses like Dante and Chaucer who could see the way the languages of Europe were heading. When Dante wrote his works, people thought it odd that he would compose such epic poetry in the regional, sub-literary dialect of Tuscany, a local language that didn’t even have a name. But Dante called it Italian, and now we all call it that.

Speaking of popularity, the Divine Comedy‘s three parts (Paradise, Purgatory, and Inferno) must be read together, but the hell volume has always been the most popular. This in spite of the fact that the Purgatory is the most distinctively Dantean, and the Paradise is the greatest poetic accomplishment. Dante’s Inferno has the most sensational imagery, which makes its appeal most immediate and direct. The creativity with which Dante distributes poetic justice to the souls in hell is indeed riveting. Especially in our increasingly post-Christian culture, we can expect that the only part of Christian doctrine people will find immediately understandable will be hell. Purgatory (either as a Roman Catholic doctrine of the afterlife, or, more palatably, as an account of the soul’s re-ordering after the pattern of virtue) and Paradise are harder for moderns to wrap their minds around, but burning in hell they think they understand.

The popularity of Dante’s Inferno over the other two parts of the Comedy, however, is not just a modern phenomenon. Here is a bit of evidence that even his contemporaries thought of him primarily as the man who knew a lot about hell.

The earliest biography of Dante is by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), who is in his own right a major contributor to world literature in Italian. In Boccaccio’s Life of Dante, you get double points on the Great Books scale: It’s a book about one of the greatest authors of all time, by another one of the greatest authors of all time. Boccaccio tells this story:

…as he was passing before a doorway where sat a group of women, one of them softly said to the others, — but not so softly but that she was distinctly heard by Dante and such as accompanied him– “Do you see the man who goes down to hell and returns when he pleases and brings back tidings of them that are below?” To which one of the others naively answered, “You must indeed say true. Do you not see how his beard is crisped and his color darkened by the heat and smoke down there?” Hearing these words spoken behind him, and knowing that they came from the innocent belief of the women he was pleased, and smiling a little as if content that they should hold such an opinion, he passed on.