The Davenant Trust, the organization that sponsors creative resourcement projects “to revitalize contemporary Reformed and evangelical discourse,” has launched a major new undertaking: the Davenant Latin Institute.

Readers of the Scriptorium may remember Davenant for its sponsorship of The Future of Protestantism event at Biola. They are also behind a number of other initiatives, including digitization and translation of key theological texts, conferences of various kinds, and all manner of fundraising, fellowships, scholarships, bursaries, and such.

But the Davenant Latin Institute is a new kind of thing for them, and I think it’s one of the most strategic and far-reaching moves such an organization could make. Why? Because if your goal is to build up Protestant theology in the present, the best thing you can do is ground it firmly in its past. Here’s what I said in my official endorsement of the institute:

Not all Latin is the same, and the standard “ecce romani” drill doesn’t dig deep enough for everybody’s needs. The Davenant Latin Institute is not only focused on theological Latin, but is uniquely designed to put the untranslated riches of early modern theological sources within the grasp of students. The world of Reformation and post-Reformation Protestant theology is still mainly a Latin world, and the Davenant Latin Institute is, to my knowledge, the only project that promises to lead students into that world.

And here’s a glimpse of what I mean. Navigate over to the Post-Reformation Digital Library and look around a little. Lots of 16th and 17th-century books there, right? and some in English, which is great. But mostly Latin. Think about that: vast quantities of the most thorough and rigorous theological writing in Protestant history is rarely tapped because it can only be studied by scholars who can read Latin, and who are specifically equipped to read the kind of Latin these authors used. It’s a weird idiom, often steeped in patristics, fluent with scholasticism, but tinged by the Renaissance’s recovery of a sense of authorial style. It tends to be heavily abbreviated, is packed with technical terms, sprinkled with Greek and Hebrew, and it’s always participating in an ongoing conversation.

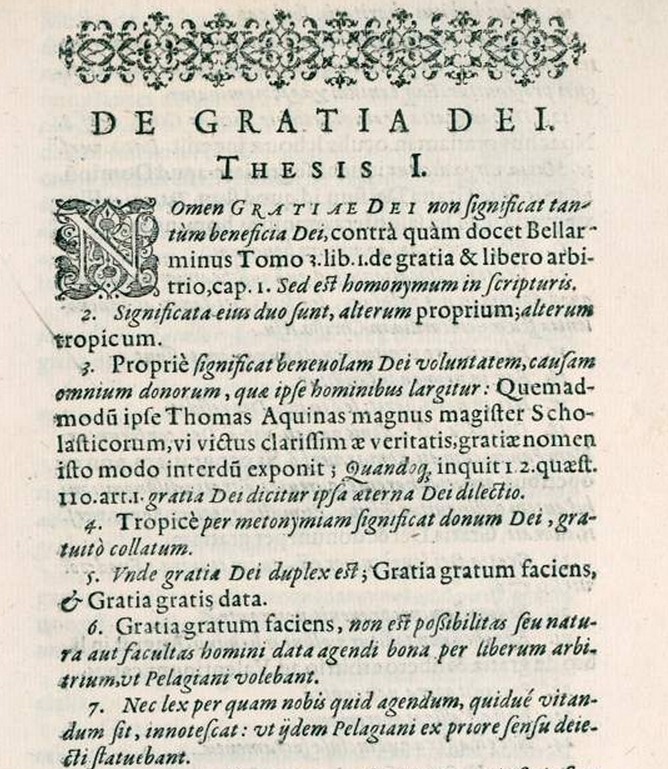

For instance, here’s one page of one work: Amandus Polanus’ treatise on grace. Polanus (1561-1610) was one of the great consolidators of Reformed theology, and his multi-volume Syntagma remained influential as long as Protestant theological education was carried out in Latin. Now the Syntagma may be coming into English at last, which will be great. But I haven’t heard of any plans to translate this little treatise on grace. And what can we see in it, at a glance? A Protestant theologian who knows his stuff: In the first paragraph, he disagrees with the definition offered by the Roman Catholic polemicist Bellarmine, and in the second paragraph he trumps him with Thomas Aquinas (ipse! magnus magister Scholasticorum, vi victus clarissimae veritatis!) Then he begins to work out his distinction between grace proper and grace figurative (tropicum), which he does by way of further distinctions. Readers of Thomas Aquinas will be excited to see the Protestant Polanus entering a close engagement with the categories of gratia gratum faciens and gratia gratis data, grace considered as the power that makes on gracious on the one hand, the grace considered as a gift freely given on the other. Pelagianism is invoked…

For instance, here’s one page of one work: Amandus Polanus’ treatise on grace. Polanus (1561-1610) was one of the great consolidators of Reformed theology, and his multi-volume Syntagma remained influential as long as Protestant theological education was carried out in Latin. Now the Syntagma may be coming into English at last, which will be great. But I haven’t heard of any plans to translate this little treatise on grace. And what can we see in it, at a glance? A Protestant theologian who knows his stuff: In the first paragraph, he disagrees with the definition offered by the Roman Catholic polemicist Bellarmine, and in the second paragraph he trumps him with Thomas Aquinas (ipse! magnus magister Scholasticorum, vi victus clarissimae veritatis!) Then he begins to work out his distinction between grace proper and grace figurative (tropicum), which he does by way of further distinctions. Readers of Thomas Aquinas will be excited to see the Protestant Polanus entering a close engagement with the categories of gratia gratum faciens and gratia gratis data, grace considered as the power that makes on gracious on the one hand, the grace considered as a gift freely given on the other. Pelagianism is invoked…

Verrrry interesting. And what does Polanus have to say about this? I DON’T KNOW BECAUSE I CAN’T READ LATIN! Or more precisely, I’m a B student in 9th grade Latin and working on it with the homeschool co-op, while knowing there’s a cap on the level of proficiency I can expect to reach since I started studying in my 40s.

It may be too late for me to throw open the books and do much of my own theologizing in dialogue with the best theological thinkers of my Protestant tradition. If I could go back to grad school, I’d have worked on Latin instead of French, I suppose.

But to younger theologians, I say: Fly, you fools! Fly to these mountains of learning, these untranslated riches of erudition. Sure, Zanchi’s going to appear in English soon. Sure, a stream of good translations will continue. But along with all this great translating, what Protestant theology could really use is a generation of thinkers who can skip lightly over the language barrier and get whatever they need from the first best thinkers in our heritage.

So check out the Davenant Latin Institute. Classes start this summer, and there are various levels to engage. Imagine a future where the generations of Protestantism aren’t cut off from each other by this linguistic divide. It’ll be a future that also puts the riches of the medieval and patristic periods back in our hands as well, but that’s another story. Let’s have a go at the early modern wall first.