Frances M. Young’s Construing the Cross is no mere exercise by a young scholar with an idea, research leave and a bibliography. Rather, this is the product of a mature and measured lifetime of study, a small window looking out at a long and patiently crafted garden. And at the heart of it all stands the work of the early theologians of the Church. In her hands that tri-color shelf of books known as the Nicene Fathers set is cast down to become a lively and supple serpent—but one which we can look upon, or better, look through, to see Christ’s atoning work in a range of new and life-giving ways.

For this is Young’s emphasis: eschewing contemporary interest in “theories,” which “purport to control and explain” (124), Young favors theōria, a “Greek term… meaning something like a ‘seeing through’… a kind of insight or spiritual rather than literalizing exegesis” (xiii). The danger, as Young sees it (and I can only concur) is that in the last 200 years or more, theologians have largely devoted their energy to chronicling, explaining, reducing and arranging past insights into the work of Christ under the guise of “theories”—a term foreign to the works they are analyzing. The result is a narrowing and ossifying of work, which, in past generations of the church, was far more lively, creative and life giving.

For this is Young’s emphasis: eschewing contemporary interest in “theories,” which “purport to control and explain” (124), Young favors theōria, a “Greek term… meaning something like a ‘seeing through’… a kind of insight or spiritual rather than literalizing exegesis” (xiii). The danger, as Young sees it (and I can only concur) is that in the last 200 years or more, theologians have largely devoted their energy to chronicling, explaining, reducing and arranging past insights into the work of Christ under the guise of “theories”—a term foreign to the works they are analyzing. The result is a narrowing and ossifying of work, which, in past generations of the church, was far more lively, creative and life giving.

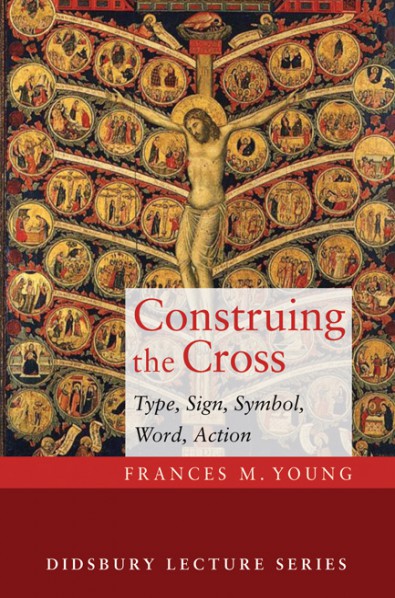

And I can only say that Young succeeds: her work is absolutely full of joy, creativity and re-appropriation. She draws on a range of theologians often neglected in such studies, including Melito of Sardis, Ephraim of Syria, Origen, Tertullian, Basil, and Justin Martyr. Complementing this approach is Young’s delightful interaction with the art of the early Christians—a noteworthy source for further study. Crucifixes, mosaics, carvings… Young excels at pulling together the art, worship and theology of the early church to re-captivate our imaginations with the work of Christ.

Particularly helpful in this regard was her use of Robin Jensen’s Understanding Early Christian Art to undermine the common view that early Christians did not depict the cross (or atonement) in their art. Jensen, relying on the work of early theologians, demonstrates the extent to which early Christians saw the cross in a myriad of images—a move Young appropriates, to further her own reflections.

Fundamentally, to engage in doctrine is to engage in worship. We are not cutting, disassembling and analyzing—we are seeking to understand and rejoice in the being and work of the triune God, who made himself the means and goal of our salvation in Jesus Christ. In the hands of Frances M. Young, the doctrine leaps out of its chains, dancing in delight. From the first few pages, I knew that I was in the hands of a master of the doctrine, which is to say a true and humble servant of the doctrine, and I was not disappointed in the least, from cover to cover.

For those interested in a little more insight into the nature of the book, three brief points may be of help.

First, this book is explicitly presented as being a deeply Wesleyan work—it is dedicated to Young’s Wesleyan grandfathers (both pastors), and Young connects her approach to the Wesleyan Quadrilateral in the introduction (xiii). While many works of atonement coming from a Wesleyan perspective look to depart from the tradition in favor of fundamentally non-violent approaches, I find in Young’s work a far more orthodox and historically indebted approach, which I can only commend as an example.

Second, the book explores the Passover and Passion (Chap. 1), Scapegoat and Sacrifice (Chap. 2), Tree of Life (Chap. 3), Signs, Symbols and Serpents (Chap. 4), and Language, Liturgy and Life (Chap. 5). The goal is to be suggestive rather than exhaustive, to open doors to further study, rather than to “sum up” or exhaustively present the early church’s view of Christ’s saving work.

Finally, while Young takes some pains to distinguish the approaches of the early church from later Medieval and Reformed explorations of the doctrine, her primary concern is the lively portrayal of her subject matter, rather than a polemic edge drawn between those areas of the church’s theology. In other words, she allows a creative appropriation to fill her canvas, leaving disputes for another day about the role of debt, penalty and judgment. My own impression is that the early church does more with these themes than Young acknowledges, but that she is nonetheless right in what they emphasize. It’s not just that I loved this book – it’s that I can’t wait to get my hands on Young’s other works. What a feast!