So John Wesley was sighted last week in an “I heart Pelagius” T-shirt, and Christian Buzzfeed has the .gif. But even if you’ve already taken the clickbait, I can ‘splain. You won’t believe what happened next.

In a recent blog post, Lee Gatiss quoted a snippet from John Wesley, a few words which certainly seem to be heartily pro-Pelagius. That’s weird because Pelagianism is the error of denying original sin, and Wesley’s longest single doctrinal treatise is a spirited defense of the doctrine of original sin. So what’s with this “Yay Pelagius” soundbite?

Lee ended his provocative note with the question, “What are we to make of that…?” and I take his ellipsis and question mark in good faith, on the assumption that he really wants to know what Wesley meant.

Tom McCall wrote a responsible response to Lee’s post, clarifying the big doctrinal and historical points tidily enough. Serious people should read that. I don’t want to write a surrejoinder to a surrejoinder, and Christmas break isn’t an apt time to spar with Calvinists (even friendly ones like Lee Gatiss). But any time is a good time to read a John Wesley sermon, so I want to offer a reading of the Wesley sermon in question.

Because that’s all you have to do to understand what Wesley meant. He was above all a preacher whose sermons changed the course of history. He didn’t write a theological system, though he had an implicit one in the back of his mind. Instead, the basic unit of his thought is the sermon. So you don’t have to survey his entire thought system, you just have to read the single sermon with due attention, to let it do its work. But since I know a little bit about Wesley’s history and background (see my book on his spirituality), I will frame this reading with (first) an observation about the year he gave the sermon, and (finally) the main dangers he habitually opposed. But mostly I’m just reading the sermon and attending to its dynamics. It’s a simple trick anybody can do at home.

The immediate literary context of the pro-Pelagius remark is Sermon 68, “The Wisdom of God’s Counsels.” It’s a sermon on Romans 11:33, “O the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God!”

The point Wesley makes in this sermon is that love of money and ease are most likely going to destroy evangelical witness in our generation, but God will raise up new bearers of the message of the gospel.

What does that have to do with Pelagius? Almost nothing. It’s a 5,000 word sermon with a very clear point, and Wesley tossed in a Pelagius reference to shake people up. Here’s how.

Wesley makes several initial moves, including elaborating the distinction between wisdom and knowledge, and then exploring how God’s wisdom is shown in directing the stars, governing the nations, and especially in guiding the church. The course of the church as it makes its way through history is, as it turns out, Wesley’s real theme. He wants to play the part of prophet here, not by predicting what is to come, but by interpreting what has happened. The primary task he sets himself in the sermon is to show how God’s wisdom is at work in directing the long flow of Christian history down to 1784, the year he preached this sermon.

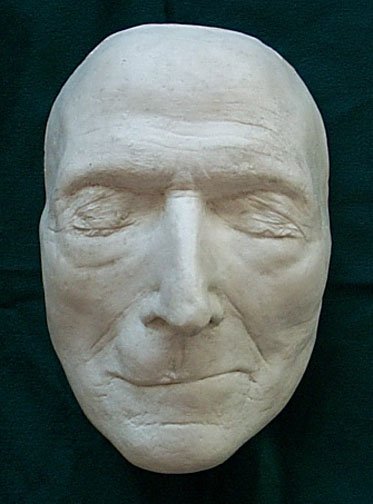

In 1784, John Wesley was an old man, in his 80s. In his writing and preaching from these last several years of his life, a new theme becomes prominent: the fear that the Methodist revival movement had begun to lose its power because its leaders were becoming wealthy and self-satisfied. He harangued his preachers about this; he wrote tracts and circular letters of warning; he preached against it whenever he could.

And in this sermon, “The Wisdom of God’s Counsels,” he attempted to view the problem of this cooling off of the red-hot Methodists in light of God’s wisdom and providence. Imagine for a moment taking up a task like this: Why is your movement getting worse, and what is God going to do about it? Update it to your context: Why is Anglicanism re-splintering as it recedes? Can any of the old mainline denominations reverse their steep decline and demographically-certain doom? Why can’t conservative Baptists get along now that they’ve expelled the liberals? What will become of the Mars Hill congregations? Why is the American evangelical ascent to the upper middle class being matched by a decline in charitable giving? What is happening, and what does God intend in all of it?

Wesley knows he can’t be dogmatic in his interpretation of God’s wisdom in the church. Where God hasn’t made his plans clear, we must speak with reserve. But “by keeping close to what he has revealed, meantime comparing the word and the work of God together, we may understand a part of his ways.” So Wesley touches lightly on the history of salvation, skipping from the biblical covenants to the early church to the Reformation, and then focusing on “what He has wrought in the present age, during the last half century; yea, and in this little corner of the world, the British islands only.” Wesley’s trying to think big in order to make a timely, local observation.

He indulges in a little bit of the mythology of the “fall of the church” from its apostolic golden age, with the Reformation featuring as the great recovery of the gospel message: “for fourteen hundred years, it was corrupted more and more, as all history shows, till scarce any either of the power or form of religion was left.” Nothing especially novel or interesting in that, except that Wesley pushes that fall all the way back to the early chapters of Acts, when Ananias and Sapphira were led by “the love of money, (“the root of all evil,”),” to make “the first breach in the community of goods!” And most of the earliest churches were compromised in one way or another by similar errors (Wesley adduces the letters to the churches from Revelation, noting the exceptions of Smyrna and Philadelphia).

By picking out this detail, Wesley is setting up his critique of his contemporaries: love of money is the culprit, love of respectability and good reputation is cooling the Methodist movement, love of security is the great enemy of the unfinished revival.

But while tracing the darkness and decline of the church, Wesley also casts about for some resources that might indicate where the true witness was kept alive. Wesley knows his official church history well, but he is lightly armed at this particular point. His instinct is to find some witnesses outside of the wealthy, established, and complacent churches: To make his point that love of money and reputation cooled the church, his witnesses must be drawn from the underside of church history. Who, he asks himself, was condemned as heretical and cast out of the church for being too hot to handle?

God always reserved a seed for himself; a few that worshipped him in spirit and in truth. I have often doubted, whether these were not the very persons whom the rich and honourable Christians, who will always have number as well as power on their side, did not stigmatize, from time to time, with the title of heretics.

Then Wesley picks two likely candidates from the halls of heresy: the second-century Montanus, who may have been too Pentecostal for the church to handle at the time; and the fifth-century Pelagius, who may have had higher standards of transformation and personal holiness than the church could handle at the time. “I have doubted,” says Wesley, “whether that arch-heretic, Montanus, was not one of the holiest men in the second century.”

Well, Montanus said some weird stuff: apparently he said the New Jerusalem was coming down in his hometown in Phrygia, suggested he was the Paraclete, and so on. But if you’re poking around in church history trying to figure out who might have been slandered and cast out for shaking things up too much, he’s a good candidate. Of course, to get to that conclusion you have to be willing to entertain a little bit of a conspiracy theory. If you hear Montanus’ worst sound bites, you have to be able to say, “I bet those words were twisted and put in his mouth because people really just didn’t like charismatics back then.”

In the eighteenth century, historians hadn’t been trying this subaltern approach to church history for long; Gottfried Arnold’s Unparteyische Kirchen- und Ketzer-historie (“Impartial Church-and-Heretic-History”) had come out in 1800. Wesley’s thumbnail sketch of who-got-slandered only works, if it works at all, for two reasons: (1) we don’t have much information at all about Montanus, and (2) what we do have is told from the point of view of enemies with a flair for the dramatic (Tertullian in particular wasn’t what you’d call temperate or balanced when he built up a good head of steam as a writer). With a little more solid information about Montanus, Wesley’s impressionistic gesture toward him would be limp.

Which brings us to Pelagius.

Yea, I would not affirm, that the arch-heretic of the fifth century, (as plentifully as he has been bespattered for many ages) was not one of the holiest men of that age, not excepting St. Augustine himself. (A wonderful saint! As full of pride, passion, bitterness, censoriousness, and as foul-mouthed to all that contradicted him, as George Fox himself.) I verily believe, the real heresy of Pelagius was neither more nor less than this: The holding that Christians may, by the grace of God, (not without it; that I take to be a mere slander) “go on to perfection;” or, in other words, “fulfil the law of Christ.”

That’s about as far as Wesley could push it; again, if he had had more information, or more reliable information about Pelagius, he couldn’t have ventured this suggestive praise, even to make his point. Wesley did go a bit further to explain why Augustine’s testimony was compromised: “When Augustine’s passions were heated, his word is not worth a rush.” I’m a big fan of Augustine, but with the protasis of heated passions, the apodosis of worthless testimony seems fair –at least I bet we could get Jerome to agree (I also note that Lee rather naughtily left the protasis unquoted, brandishing only the “not worth a rush” bit).

For the rest of the sermon, Wesley drives home his point that money is ruining the people called Methodists. Their preachers, in particular, are waxing fat and lazy. How they have declined from their first days:

But as these young Preachers grew in years, they did not all grow in grace. Several of them indeed increased in other knowledge; but not proportionably in the knowledge of God. They grew less simple, less alive to God, and less devoted to him. They were less zealous for God; and, consequently, less active, less diligent in his service. Some of them began to desire the praise of men, and not the praise of God only; some to be weary of a wandering life, and so to seek ease and quietness. Some began again to fear the faces of men; to be ashamed of their calling; to be unwilling to deny themselves, to take up their cross daily, “and endure hardship as good soldiers of Jesus Christ.” Wherever these Preachers laboured, there was not much fruit of their labours. Their word was not, as formerly, clothed with power: It carried with it no demonstration of the Spirit. The same faintness of spirit was in their private conversation.

Wesley admits that there were several causes of the decline, but points out love of money as the main culprit: “But of all temptations, none so struck at the whole work of God as “the deceitfulness of riches;” a thousand melancholy proofs of which I have seen within these last fifty years. Deceitful are they indeed! For who will believe they do him the least harm?”

John Wesley was well known for his stewardship motto, “Earn all you can, save all you can, give all you can.” But the Methodist preachers have begun to apply only two thirds of it:

They save all they can, by cutting off all needless expense; by adding frugality to diligence. And so far all is right. This is the duty of every one that fears God. But they do not give all they can; without which they must needs grow more and more earthly-minded. Their affections will cleave to the dust more and more; and they will have less and less communion with God.

And then Wesley begins forcing the application questions:

Is not this your case? Do you not seek the praise of men more than the praise of God? Do not you lay up , or at least desire and endeavor to “lay up, treasures on earth?” Are you not then (deal faithfully with your own soul!) more and more alive to the world, and, consequently, more and more dead to God? It cannot be otherwise. That must follow, unless you give all you can, as well as gain and save all you can. There is no other way under heaven to prevent your money from sinking you lower than the grave! For “if any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him.”

With regard to pride:

If you are increased in goods, do not you know that these things are so? Do you contract no intimacy with worldly men? Do not you converse with them more than duty requires? Are you in no danger of pride? Of thinking yourself better than your poor, dirty neighbours? Do you never resent, yea, and revenge an affront? Do you never render evil for evil? Do not you give way to indolence or love of ease? Do you deny yourself, and take up your cross daily? Do you constantly rise as early as you did once? Why not? Is not your soul as precious now as it was then? How often do you fast? Is not this a duty to you, as much as to a day-labourer?

And accountability:

But if you are wanting in this, or any other respect, who will tell you of it? Who dares tell you the plain truth, but those who neither hope nor fear any thing from you? And if any venture to deal plainly with you, how hard is it for you to bear it! Are not you far less reprovable, far less advisable, than when you were poor?

Wesley wraps up this section of the sermon by declaring to God, “Lord, I have warned them! but if they will not be warned, what can I do more? I can only “give them up unto their own heart’s lusts, and let them follow their own imaginations!””

What does this have to do with the wisdom of God in the managing of the church? Wesley assures his listeners, “the Lord hath no need of you; his work doth not depend upon your help.” God will gladly and speedily raise up a new generation of preachers to carry the work forward, casting aside the workers who have become useless through their love of money, unprofitable through thirst for profit.

That is the obvious point of this sermon, easily apparent in a simple reading of it, and evident from the longer quotations presented here. With a little more background knowledge of Wesley’s preaching, we could add that he is always on the lookout against two dangers in the spiritual life: formalism and antinomianism. Formalism: the tendency to think that religion consists largely in externals, in a course of outward actions, liturgical observances, or behaviors. Antinomianism; thinking of oneself as above God’s law, and treating God as one who has no moral authority to command the believer. It’s not hard to see how love of money and respectability would lead directly into both of these errors.

I’m not sure I share Wesley’s prudential decision that formalism and antinomianism are the main dangers that need to be opposed, at least in our own times. I’m also not certain that love of money is the crippling temptation of contemporary evangelicalism. It might be, maybe Ed Stetzer has some stats on it. I do think the parallel temptation, love of respectability, is taking many Christians off of the front lines. Any voice that can reach us on these issues is one that ought to be attended to.

And that reminds me of how an earlier generation of Calvinists regarded the message of John Wesley. Wesley was not somebody to argue against, or to silence by pointedly ignoring, or to warn people away from by broadcasting the rumor that he was guilty by association with heresy. Instead, Calvinistic Anglicans like J.C. Ryle thought of him as one of the best resources in the evangelical toolbox for maybe, just maybe, reviving a dying church movement:

I am afraid that most of us are half asleep, and those that are a little awake have not begun to feel. It will be time for us to find fault with John and Charles Wesley, not when we discover their mistakes, but when we have cured our own. When we shall have more piety than they, more fire, more grace, more burning love, more intense unselfishness, then, and not till then, may we begin to find fault and criticize.