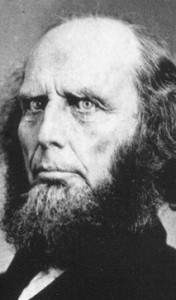

Today (August 29) is the birthday of Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875), whose accomplishments as a revivalist preacher are staggering. The most striking statistic usually reported is that when he came to Rochester, the population tripled but the crime rate dropped by two-thirds. Other preachers might be bold enough to preach against the evils of saloons, but when Finney came to town, the saloon owners would close up shop and hang a sign on their doors telling would-be customers to go to the Finney meetings. Hundreds of towns reported revivals connected with his work, and some people put the numbers of conversions and church memberships in the hundreds of thousands. He preached moral reform and called for the abolition of slavery in a way that burned deeply into the conscience of the nation.

Today (August 29) is the birthday of Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875), whose accomplishments as a revivalist preacher are staggering. The most striking statistic usually reported is that when he came to Rochester, the population tripled but the crime rate dropped by two-thirds. Other preachers might be bold enough to preach against the evils of saloons, but when Finney came to town, the saloon owners would close up shop and hang a sign on their doors telling would-be customers to go to the Finney meetings. Hundreds of towns reported revivals connected with his work, and some people put the numbers of conversions and church memberships in the hundreds of thousands. He preached moral reform and called for the abolition of slavery in a way that burned deeply into the conscience of the nation.

I grew up hearing Finney connected with all sorts of great accomplishments, and the name Finney is routinely ranked in that list that goes Edwards, Whitefield, Finney, Moody, Torrey, Graham, etc. Moody, Torrey, and Graham even name him as someone who influenced their own work.

So when I started studying theology on my own, and saw that this epochal American soul-winner had also authored a Systematic Theology, I was eager to read it. I admit to being an incurable theology nerd: There’s almost nothing I enjoy as much as cracking open a system of doctrine I’ve never read before. And one by a certified revival-sparker? I’m in!

I can still remember the day I went to the library and got Finney’s Systematic Theology. I skimmed through the introduction and raced for the first page of the main text. How would he start his lectures on systematic theology? What decisions had he made about presenting this system of truth that had rocked American history?

Page 1: How we come to know certain truths. Well, that’s a little dry, but a lot of theologies start out with a bit of epistemology. Skim, skim, lecture 2: Moral Government. Hm, that’s odd. But let’s give him the benefit of the doubt, maybe he’s getting his momentum for a law-grace thing. No, this is a long chapter with a big list of characteristics of moral law. Well, let’s jump over it and see what tasty theological treats come next.

Lecture 3: Moral Government continued.

Lecture 4: Moral Government continued.

Lecture 5, Foundations of Moral Obligation.

Lecture 6: Foundations of Moral Obligation: False Theories.

Lecture 7: the same.

Lecture 8: the same.

Lecture 9: Foundations of Obligation… Lecture 10, same; Lecture 11, “summing up.” Ah! Now we can get on to the next doctrinal subject.

Ugh, no. Lecture 12: Foundation of Moral Obligation…Practical Bearings of the Different Theories…

Lectures 13 through 17, all Moral Government.

Hundreds of pages in, we finally get to some “Attributes of Love.” Divine attributes, maybe? Can we start a doctrine of God somewhere in here? No, these are attributes of “that love which constitutes obedience to the law.” And then this goes on for pages.

My excitement long since evaporated by the withering blast of red-hot moralism, I slogged through my survey of the rest of the lectures. Oh look, a governmental theory of the atonement instead of vicarious punishment. And no original sin. Lots of chapters on sanctification, but they are mostly controversial theology about perfection.

Here, under justification, there is a list of conditions. “Conditions” for justification; That’s awkward language, but it admits of an orthodox interpretation. The conditions are faith, repentance, and …sanctification.

Wait. Sanctification a condition of justification? As in, I’m only accepted by God when I’m morally right? Yes, it’s all there in cold print, with vigorous rebuttals of other positions involving imputation or legal fictions. That sounds more Roman Catholic than Presbyterian (and Finney was a Presbyterian of some sort). But Finney’s denial of original sin is not even acceptable to Roman Catholics, it seems to shoot past Rome and issue in outright Pelagianism. I know he was reacting against a cold hyper-Calvinism, and trying to awaken a morally sleepy nation, but excuses and situational explanations can only cover so much bad doctrine.

Well, Finney’s Systematic Theology, by my lights, is just a train wreck. Maybe my expectations would have been more realistic if the work had a different title: A title like “Law and Obligations” or something. My expectations might also have been lower if Charles Finney were not routinely praised as a great evangelical preacher. This theology of his, I hate to say it, but it’s just not evangelical. I listen in vain for good news in this moralistic logic-chopping.

I’ve never gone back to dig deeper into Finney. There may be a more fair way of understanding his writings sympathetically, but I’m a John Wesley fan who grew up Pentecostal and am basically pro-revival, and that should set me up for a pretty sympathetic reading. His autobiographical work is interesting, but I’ve seen more than enough of that theology of his. R. A. Torrey wrote a classic explanation of Why God Used Dwight L. Moody. The big question with Finney, though, is how God used him, when his theology was this messed up.