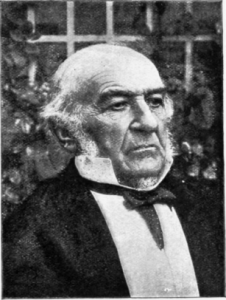

Today (December 29) is the birthday of William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898), who has been called “the most eminent of the eminent Victorians.” Gladstone the politician dominated British history throughout the bulk of the nineteenth century: He became a Member of Parliament in 1832, and remained in high offices until 1895, serving four times as Prime Minister, and four times as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His tenure in the UK’s political life tracked very closely with Queen Victoria’s long reign, which stretched from 1837 to 1901.

Today (December 29) is the birthday of William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898), who has been called “the most eminent of the eminent Victorians.” Gladstone the politician dominated British history throughout the bulk of the nineteenth century: He became a Member of Parliament in 1832, and remained in high offices until 1895, serving four times as Prime Minister, and four times as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His tenure in the UK’s political life tracked very closely with Queen Victoria’s long reign, which stretched from 1837 to 1901.

Gladstone had a fervently evangelical upbringing and a classical education (Eton and Oxford). Throughout his life, the Bible was his intellectual foundation, and his five favorite dialogue partners were Homer, Aristotle, Augustine, Dante, and Butler. He was a political animal and a man of action, but he was always very bookish as well. His books on Homer are still very engaging introductions to the poet.

His most famous theological book, though, is 1891’s The Impregnable Rock of Holy Scripture, a popular apologetic for the Bible in the face of skeptical criticism. Gladstone wrote it as an amateur theologian and a shrewd observer of the latest developments on his contemporary theological scene, so the work is as dated now as it was immediately relevant at the end of the nineteenth century. It is certainly worth reading for insight into Victorian Christianity, but large portions of it have abiding value as a well-crafted and large-minded commendation of the trustworthiness of Scripture.

Gladstone’s sentences are long, balanced, and circuitous, but once you develop an ear for the intelligence and authoritarianism of his cadences, they make for pleasant reading. Here is a perfect example of Gladstone’s prose, from the introductory chapter:

What I would specially press upon those to whom I write is that they should look broadly and largely at the subject of Holy Scripture, especially of the Scriptures of the older dispensation, which are, so to speak, farther from the eye, and should never allow themselves to be won away from that broad and large contemplation into discussions which, though in their own place legitimate –nay, needful– yet are secondary, and therefore, when substituted for the primary, are worse than frivolous. I do not ask this from them as philosophers or as Christians, but as men of sense. I ask them to look at the subject as they would look at the British Constitution, or at the poetry of Shakespeare.

The Impregnable Rock is the Christian view of Scripture, presented to “men of sense” in Victorian England.

The central image throughout the book is that the tide of historical criticism is coming in, rising fast, and making a tumult of noisy confusion. But Scripture, in Gladstone’s metaphor, is a rock that will stand against the swelling waves, and the tone of the book never descends to fearful apprehension or panic. Instead, Gladstone calmly and confidently presents his case. He defends Scripture without ever sounding defensive, and when he undermines certain critics, he rarely adopts a tone of counter-aggression. He does indulge in some mockery of the unwarranted cockiness of some of the critics, whom he calls Contradictionists, who report Biblical discrepancies “in a tone of confidence rising into the paean of triumph.” The blustering T. H. Huxley, inevitably, leaves himself wide open for numerous damaging blows from Gladstone’s wit.

Many Victorians were too nice for the Bible. It is well known that upper-class Victorian England became so well-mannered and polite that it found itself rather embarrassed about the Bible’s morality. For some of the genteel souls of the period, the most prurient literature they would admit into their homes were the stories of the Old Testament. All that nudity, reproductive irregularity, polygamy, and hand-to-hand combat. Disgusting! For today’s audience, the most instructive passages of Impregnable Rock might be Gladstone’s handling of his contemporaries’ moral objections to the Bible. Huxley takes a deserved thrashing here: He reads the story of Jesus casting demons into a herd of swine, and sneers that this story implicates Jesus in “wanton destruction of other people’s property,” a “misdemeanor of evil example.” The evangelist who reports it has no “inkling of the legal and moral difficulties of the case.”

Gladstone retorts:

So then, after eighteen centuries of worship offered to our Lord by the most cultivated, the most developed, and the most progressive, portion of the human race, it has been reserved to a scientific inquirer to discover that he was no better than a law-breaker and an evil-doer. It is sometimes said that the greatest discoveries are the most simple. And this, if really a discovery, is the simplest of them all. … The ordinary reader can only put the wondering question, How, in such a matter, came the honors of originality to be reserved to our time and to Professor Huxley?

After spending a few pages investigating and interpreting the story in light of history and culture, Gladstone concludes, “Mr Huxley, exercising his rapid judgment on the text, does not appear to have encumbered himself with the labor of inquiring what anybody else had known or said about it.”

The final chapter of the book is the best. In it, Gladstone declares that ages of faith may come rolling in with the tide, and they may roll back out again in their season. He does not quote Matthew Arnold by name, or refer to his poem Dover Beach with its image of the age of faith receding, but he does seem to be responding to that mentality. In fact, he reverses the image: It is the age of skepticism which rolls in like a tide and will inevitably roll back out, leaving the impregnable rock unmoved. The tide of criticism was certainly rising, but it had risen before and would do so again, and was no cause for alarm. In fact, the Christian could even afford to ponder the beneficial effects of the rise and fall of the latest critical movement:

I have said that when it has done its work it may cease to be. For doubtless it has a work to do. The wave that breaks and foams upon the rock exhibits to us not merely, as it might seem, a picture of violence and a source of danger, but a fraction of the vast oceanic movement, which is the indispensable condition of health and purity both to the water and the air, and to the populations by which they are respectively inhabited. If we believe in Providential government, we might rationally believe, even where we did not see, that those boastful and even powerful agencies are not without their purposes prefigured, and bounded too, in the counsels of God. It seems, however, not difficult to discern a portion of those purposes; which may have been, first, to dispel the lethargy and stimulate the zeal of believers; and, secondly, to admonish their faith to keep terms with reason by testing it at all its points; lest fancy, or pride, or indolence, or the intolerant spirit of sect or party, should have imported into their beliefs merely human elements that it may be very needful to eject.

Gladstone writes with the wisdom of a statesman who believes “in Providential government,” and knows that God must have his reasons for bringing a critical age upon his generation. Impregnable Rock is full of moving prose and good sense. Gladstone makes rather too many concessions to the assured results of his day’s critical thinking. He is certainly not an inerrantist, and sets forth a constructive case for the permissibility of a wide range of inconsistencies in Scripture as we have it now. He goes far enough in that direction to call into question the larger, more foundational doctrine of verbal inspiration, without giving any indications that he has reflected on all of the implications of his maneuvers. There is a similar looseness in his repeated engagements with the opening chapters of Genesis, though in that case he seems more aware of what is at stake.

Gladstone’s Impregnable Rock of Holy Scripture remained popular well into the twentieth century, even among those who took a much more conservative line than he did on a number of critical issues. The conservative evangelicals who organized the early fundamentalist movement were glad to have the prestigious name of a great man like Prime Minister Gladstone behind them. But they were not just credibility-mongering when they recommended Impregnable Rock. They knew a wise approach to public reasoning about the faith when they read it.