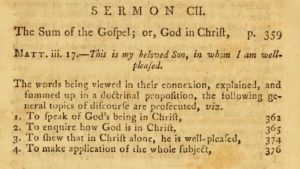

In a sermon on Matt 3:17 (“This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased”), Ralph Erskine (1685–1752) expounds the thesis that “God was in Christ.” The main thrust of the sermon is that there is a great difference between how God can be encountered in Christ as opposed to outside of Christ. “God out of Christ is a threatening God,” says Erskine, because he is a dishonored God, and the “Christless sinner” cannot safely approach him. But when we “consider what God is in Christ,” we encounter God as reconciled, well-pleased in his son, and therefore “a nearly approaching God, a nearly related God.” This central message is why Erskine gave this sermon the main title, “The Sum of the Gospel.”

In a sermon on Matt 3:17 (“This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well-pleased”), Ralph Erskine (1685–1752) expounds the thesis that “God was in Christ.” The main thrust of the sermon is that there is a great difference between how God can be encountered in Christ as opposed to outside of Christ. “God out of Christ is a threatening God,” says Erskine, because he is a dishonored God, and the “Christless sinner” cannot safely approach him. But when we “consider what God is in Christ,” we encounter God as reconciled, well-pleased in his son, and therefore “a nearly approaching God, a nearly related God.” This central message is why Erskine gave this sermon the main title, “The Sum of the Gospel.”

But the sub-title is “God in Christ,” and Erskine goes out of his way to draw attention to God’s availability in Christ. To put it in terms of the entire title, Erskine asserts at length that the sum of the gospel is having God in Christ.

It is at this point that Erskine does something bold. I think he is concerned that a certain vague and semi-incoherent way of thinking about the Trinity can actually have the result of undercutting total confidence that we have God in Christ. The kind of vague thinking I’m talking about would hear the promise, “God is in Christ,” and draw back a bit, thinking, “Well, a third of God is in Christ: the Son third. But, y’know, God the Father isn’t, because Trinity stuff reasons.” So Erskine leans into the implied objection, and argues that, if you press through superficial trinitarianism to the actual, classic trinitarianism of the confessions and catechisms, you can wholeheartedly confess God in Christ. In fact, you can say, with perfect orthodoxy, as Erskine does: “All the persons of the Godhead are in Christ; I mean, God the Father is in Christ; God the Son is in Christ; God the Holy Ghost is in Christ; one God, in three persons is in Christ.”

Let me immediately affirm the important point that it is never orthodox to say that the Father or the Spirit were incarnate. If you can’t read Erskine’s sentences above without falling into that error, you should probably avert your eyes for now, because the idea of an incarnate Father or Spirit would be the sort of theological error that we would refer to, using technical theological language, as A Big Uh-Oh.

But Erskine isn’t saying that the whole Trinity was incarnate in Christ. He’s saying that the whole Trinity was in Christ. In the following senses:

1. God the Father is in Christ; Believest thou not that I am in the Father, and the Father in me (John 14:10). And ver. 11, Believe me, that I am in the Father, and the Father in me. And hence he is called the way to the Father, ver. 6. And there is no coming to the Father but in him, because the Father is in him; that is, even the first person of the glorious Trinity; and yet not excluding his being the way to the other persons of the glorious Trinity.

When he takes up the subject of Christ as “the way to the other persons,” Erskine includes a meditation on the ways God the Son is in Christ. Fortunately, Erskine has the entire classical toolbox of distinctions ready at hand for this:

2. God the Son is in Christ: as God the Son is Christ; so God the Son is in Christ: that is to say, God the Son, considered as the second person of the glorious Trinity, is in Christ, considered as Mediator between God and man.

The divine person of the Son is as inaccessible to us, as the divine person of the Father: and we need a mediator between him and us as he is God, as well as between the Father and us: for as there is an essential Oneness between him and the Father; “I and my Father are one,” John 10:30: so there is a personal equality; “Being in the form of God he thought it no robbery to be equal with God,” Phil 2:6.

Therefore his infinite holiness and justice must be satisfied, as well as the Father’s, by the doing and dying of Christ, as Mediator, otherwise we could never have access to God; Christ the Son, being God co equal and co essential with the Father: and hence, Christ, as Mediator, is the way to himself, as God, as well as he is the way to the Father; because he is the way to God: “Christ having once suffered for sin the just for the unjust that he might bring us to God,” 1 Pet 3:18. “By him we believe in God who raised him from the dead and gave him glory that our faith and hope might be in God,” I Pet 1:21.

And hence as Saviour, God-man; and Mediator, between God and man, he calls us to come to himself, as God. “Look to me and be saved all the ends of the earth for I am God and there is none else.” Isa 45:22. As Mediator, he is the means by whom; and as God, he is the end, to whom we come.

Here you see it is necessary we understand and distinguish between Christ considered

essentially, as to his divine nature, and as he is one with the Father; and

personally, as to his divine person and as he is equal with the Father; and

economically, as to his divine office of Mediator, and as he is God’s Servant in the work of our redemption: Servant to himself, as well as to the Father, while he came to fulfil his own law, and satisfy his own justice, being in this service considered as a middle person between God and man, and that contradistinct from his being the middle person between the Father and the Holy Ghost.

That was the hard part, and I think if you track carefully with Erskine, you can see that the distinctions all help him say things that need to be said. God the Son is in Christ in a unique way, distinct from the way the Father and the Spirit are in Christ; but he is also in Christ in the same way as the Father and Spirit. Therefore all the things we say about coming to the Father in Christ also apply, without cancelling what we recognize in the Son’s unique incarnation. Erskine is pointing out that the Bible teaches, and classical trinitarianism confesses, more than we conventionally think, rather than less.

After that, the pneumatology is relatively straightforward. There is an anointing of the Spirit to distinguish, lest we think that this anointing is the only way the Spirit is in Christ. That anointing is true, but the Spirit too is in Christ as God, just as the Father and the Son are:

3. God the Holy Ghost is in Christ: The third person of the glorious Trinity, proceeding from the Father and the Son, he also is in Christ, reconciling the world to himself, 2 Cor 5:20; for he is one God with the Father and the Son: “There are three that bear record in heaven the Father the Word and the Holy Ghost and these three are one,” 1 John 5:7.¹

When I say the Holy Ghost is in Christ, I mean not here the supereminent unction of the Spirit, that is so much spoken of in scripture, his being anointed with the Spirit above measure to qualify him for his mediatorial office; but I mean that the Holy Ghost, who is one God with the Father and the Son, is in Christ, reconciled in Christ, satisfied in Christ, appeased in Christ, as well as the Father and the Son ;for God is one: and it is God Father, Son ,and Holy Ghost that was offended by sin; and it is this God Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, that is reconciled, through the mediation and satisfaction of Christ; so that if this reconciliation had not been made, we could have approached to none of the persons of the glorious Trinity with acceptance; but now access is made to all alike, because access is made to God, or to the divine nature which is the same in all the three persons.

Most of us aren’t accustomed to keeping so many channels open at the same time when thinking about God in Christ. But Erskine, without even being an especially scholastic preacher, was doctrinally well-formed enough to know how much was going on in the gospel accomplished by the incarnate Son who was one of the Trinity. He could run up and down the distinctions and confess Christ as God (essential), Son (personal), and mediator (economic), without worrying that the layers were cancelling each other out.

____________________

¹I know, it’s the Johannine Comma; just pretend he’s using it for traditional illustration rather than for proof. It was like 1750.