Romans 12, at first glance, can seem like a sudden change of subject from the high theologizing of the first 11 chapters. As Paul turns from explaining the gospel, to exhorting his Roman readers, even his writing style shifts from longer sentences and complex arguments to brief commands in a more straightforward diction.

But he is not really changing the subject. In fact, all of the commands he gives flow from the teaching he has just done. Any number of good commentaries can help you trace the connection, and any expositor who asks what 12:1’s “therefore” is there for is likely to come up with good answers.

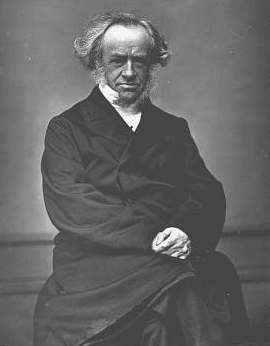

Robert Candlish (1806-1873)’s book on Romans 12 is especially eloquent about the link. In fact, the whole book is a sustained meditation showing “how thoroughly the ethics of the Gospel are impregnated with the spirit of its theology.” From the point of view of the ethical commands of the final chapters, Candlish looks back on the doctrinal section and re-describes it as a study in God’s behavior towards us. We have been studying, for 11 chapters, how God behaves. Now we turn to the question of our own behavior, and Paul shows how it ought to be shaped by God’s. Candlish says:

Man’s right conduct, in all the relations in which he is placed, consists essentially in his knowing, and believing, and sympathizing with what may be called the conduct of God. Man feels and acts rightly just in proportion as he understands, by divine teaching, how God himself feels and acts in his great plan of saving mercy.

It’s not enough to say “God is nice, so I should be nice.” Candlish emphasizes the particularity, the details, of God’s conduct, and our need for close study of this “divine teaching.” A person acts rightly “just in proportion as he understands” God’s acts and even God’s feelings. Nor is the main task reducible to an intellectual one, because Candlish insists that we must do 3 things: Know it, believe it, and sympathize with it. This is enough to make you want to re-read Romans 1-11 more carefully before going on to chapters 12-16, and that’s the basic idea. In fact, Candlish crams as much of the doctrinal content of Romans as he can into each sentence as he moves forward to the ethics:

What is required of me is that, on the one hand, I apprehend God’s sovereign grace, in his justification of the unrighteous through faith in the righteousness of his Son, and in his choice and calling of the unworthy and the unwilling according to his own mere good pleasure; and then, on the other hand, that apprehending this sovereign grace as ruling God’s treatment of me, I enter into the spirit of it, and apply it myself to all with whom I have anything to do, for ruling my treatment of them.

Christian conduct is a matter of entering into the spirit of God’s conduct. Insofar as the Spirit makes it possible for us, we are to treat others as God the Father has treated us in Christ. If it can be reduced to a matter of following certain principles, those principles are first and foremost principles of God’s action. We are to pay constant attention to what God has done, comprehend what principles have guided his conduct toward us, and then let those same principles guide us in our conduct toward others.

The proof of this approach is in the details. Read Romans 12 with this in mind (or check out Candlish’s book-length commentary), and watch how Paul dances back and forth between God’s conduct and ours. From the opening image of our offering a sacrifice, to the final verses about withholding our own wrath as we leave room for God’s, Paul situates our conduct inside the more comprehensive reflection on how God has treated us in Christ, whose sacrifice and judgement establish, enable, relativize, and outflank ours.