Question: “Do you like Kipling?”

Answer: “I don’t know, I’ve never kippled.”

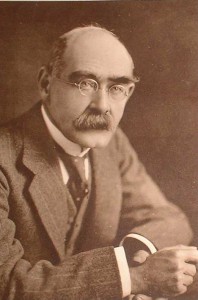

Today (December 30) is the birthday of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), the enormously popular writer who was the first English author to win the Nobel Prize in literature (1907) in his early 40s.

But aside from a couple of childrens’ stories (The Jungle Book and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi), most of Kipling’s voluminous output stays on the shelves these days. Who reads Kipling, and how did he drop off the literary scene so completely in a few decades?

There are many reasons, but let’s just get the biggest one in front of us right away:

Take up the White Man’s burden–

Send forth the best ye breed–

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild–

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

That first stanza of Kipling’s secular hymn to western imperialism was apparently first drafted to commemorate Victoria’s sixtieth year on the throne, but Kipling published it instead to celebrate the U.S. occupation of the Philippines. Pity the white races, whose God-given task is to sacrifice themselves in bringing Euro-American values to those “half-devil and half-child” peoples. Blend that together with a world-weariness and disillusionment, stir in some cynical post-Christian civil religion, and you’ve got Kipling stew.

This kind of thing is all most people need to set Kipling aside and look elsewhere for their entertainment. And I can hardly blame anybody who finds Mr. White Man’s Burden unreadable. But if you have a higher tolerance for the unacceptable views of yesteryear –which you really do need to cultivate if you’re going to read old books from any culture– there is much instruction and much fun to be had in the works of Rudyard Kipling.

C. S. Lewis described Kipling’s polarizing effect: “Kipling is intensely loved and hated. Hardly any reader likes him a little. Those who admire him will defend him tooth and nail, and resent unfavourable criticism of him as if he were a mistress or a country rather than a writer. The other side reject him with something like personal hatred.” For his own part, Lewis had to admit that he fell into neither camp, but alternated between both. “I have been reading him off and on all my life, and I never return to him without renewed admiration. I have never at any time been able to understand how a man of taste could doubt that Kipling is a very great artist.”

Lewis apparently took his Kipling by binges, and felt all the regret and sickness that follows a binge:

One moment I am filled with delight at the variety and solidity of his imagination; and then, at the very next moment, I am sick, sick to death of the whole Kipling world. Of course, one can reach temporary saturation point with any author; there comes an evening when even Boswell or Virgil will do no longer. But one parts from them a friend: one knows one will want them another day; and in the interval one thinks of them with pleasure. But I mean something quite different from that; I mean a real disenchantment, a recoil which makes the Kipling world for the moment, not dull (it is never that), but unendurable — a heavy, glaring, suffocating monstrosity. It is the difference between feeling that, one the whole, you would not like another slice of bread and butter just now, and wondering, as your gorge rises, how you could ever have imagined that you liked vodka.

Archbishop Rowan Williams has recently said, with characteristic indirectness, that “sometimes when Kipling, rather like Dostoevsky, tried to spell out in prose and in non-fiction what he thought he was most deeply about, he said things that were neither coherent nor edifying. But he knew more than he knew that he knew, and his work comes from deeper places than prose or theory.”

These are rather backhanded recommendations of the writings of Rudyard Kipling. But they are recommendations, and I too recommend reading some Kipling. His poems are so catchy and immediate that they are almost a guilty pleasure. Surely nothing so readable, so energetic, so easy to grasp at first glance, can be great literature! But when it’s Kipling, it can be; and much of it is.