So if you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ who is your life is revealed, then you also will be revealed with him in glory.

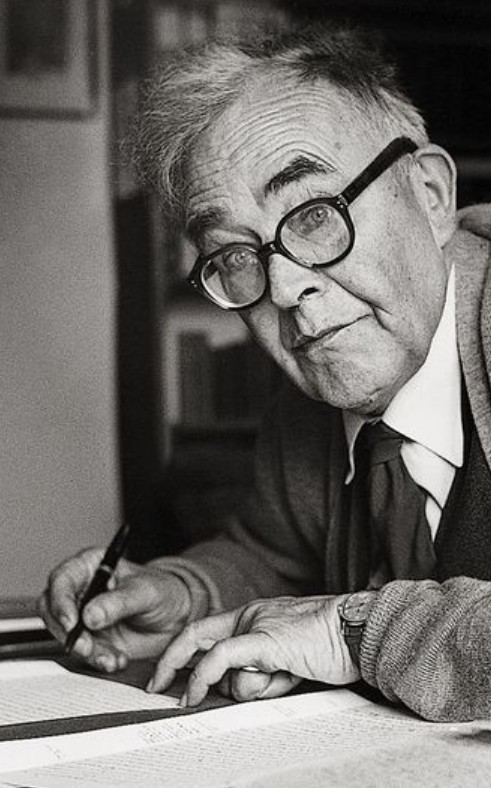

This little phrase, “hidden with Christ in God,” is one that commended itself to Karl Barth. Though I’m not aware of any location where he offers really extended treatments of it, Barth came back to the phrase again and again. At one point he called it “the basic Pauline perception…which is that of all Scripture.”

Quite a claim! “Hidden with Christ in God” is how Scripture sees everything.

Some of what Barth means by that becomes evident if you recognize in it his pronounced methodological christocentrism. The context is CD II/1, where he’s describing where knowledge of God comes from. It comes from God’s readiness to be known, which causes humanity’s readiness to know. Both readinesses come together in Christ. The result is that if we raise the question, “where does human readiness to know God come from” and are tempted to answer it anthropologically (Protestant liberalism, especially downstream from Ritschl) or ecclesiologically (Roman Catholicism, especially since Vatican I), we should stop in our tracks. When it comes to knowledge of God, “anthropological and ecclesiological assertions arise only as they are borrowed from Christology.”

This is where Barth invokes Colossians 3:3 as the “the basic Pauline perception” which we have “to take in blind seriousness” if we are to understand how humans can know God. Our life is hidden:

With Christ: never at all apart from Him, never at all independently of Him, never at all in and for itself. Man never at all exists in himself ….Man exists in Jesus Christ and in Him alone; as he also finds God in Jesus Christ and in Him alone. (CD II/1, 149)

(This quotable passage from II/1 has been discussed by Hunsinger (How to Read Karl Barth, 37-38) and Nimmo (Being in Action, 97).)

It makes sense that if knowledge of God involves a divine pole and a human pole, Barth would find both divine and human in Jesus Christ the God-Man.

The theme of hiddenness is also evocative, and for Barth it signals the way in which our access to God is not something directly available to us: it is not self-evident, or merely analytically true of human nature in itself, or subject to human manipulation. A bit earlier in II/1, without reference to the language of Colossians, Barth had pointed out that

The fact that God is revealed to us is then grace. Grace is the majesty, the freedom, the undeservedness, the unexpectedness, the newness, the arbitrariness, in which the relationship to God and therefore the possibility of knowing Him is opened up to man by God Himself. (74)

Decades, and thousands of pages, later, Barth would return to Colossians 3:3, in his doctrine of reconciliation. In this context, he presses the question of why this life of ours must be hidden. Why can’t we lay hold of its reality, know it directly, or see it openly and unequivocally as our own life and the life of the world? He answers that the hiddenness of our lives with Christ corresponds to the tension between the resurrection and the second coming of Christ: Christ is risen, and therefore our life in him is evident. But he has gone to a place on high from which he shall return, and therefore our life in him is concealed. That is, the although the real future of our salvation is present in the resurrection in all its fullness, the full development of Christ’s lordship is something we must still look forward to.

Barth argues that when Christ says, “I will return,” his return has three forms: he returns to his disciples after his death and burial, at the resurrection. He returns to his disciples after his ascension in the person of and by the ministry of the Holy Spirit, at Pentecost. And he will return to his disciples when he comes to judge the living and the dead, at the parousia. These are three forms of the return of Christ, and they mutually inform each other.

This is why Barth can say that in the second coming of Christ, this same event of Christ’s resurrection will be “repeated and renewed and consummated.” (IV/3;318-9) Developing this idea further, Barth asserts that the best analogy for the resurrection of Christ is the Christian in affliction. (IV/3:645)

Finally, in the fragment that is Church Dogmatics IV/4, Barth refers to the hiddenness of our life with Christ in God in the context of baptism: baptism is the confession by the entire community that their old lives have been put to death with Christ, and that their new lives are not their work but God’s. The pledges and oaths sworn by the entire community at baptism are not promises to undertake a new project of sanctification, but an energetic affirmation of the sanctification which has come to them in Jesus Christ. They join forces in saying Yes to God’s Yes, “not to their own good will, not to their faith, but in great thankfulness to the divine conclusion…” (IV/4:161)