I recently described how I read the Gospel of Matthew looking for an understanding of salvation: by keeping Paul in the back of my mind, but not letting him get in the front of my mind.

I recently described how I read the Gospel of Matthew looking for an understanding of salvation: by keeping Paul in the back of my mind, but not letting him get in the front of my mind.

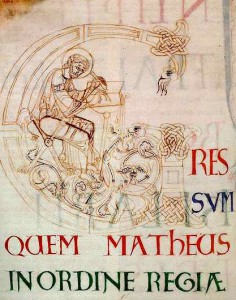

I wasn’t claiming to be original, just describing and recommending the kind of Bible reading that I think is theologically and exegetically responsible. But consider just how deeply unoriginal I was being: Reading Matthew with Pauline theology in mind goes way back to at least Hilary of Poitiers (c. 310 – c. 368), whose Matthew commentary is saturated with the theology of Paul.

In an article entitled “Hilary of Poitiers and Justification by Faith According to the Gospel of Matthew” (Pro Ecclesia, Fall 2007) D. H. Williams of Baylor explains what Hilary was up to in this earliest complete Latin commentary to come down to us. There’s a lot to say about the anti-Arian theology: Hilary has been nicknamed “the hammer of the Arians,” is most famous for his excellent book On the Trinity, and his commentary on Matthew was written about 25 years after Nicaea. But there’s not just christology in his Matthew commentary, there’s lots of soteriology:

What comes as a surprise to the reader is that the overriding theology in this Matthean commentary is very evidently Pauline. Indeed, it is not an overstatement to say that Hilary integrates Paul’s concepts and language more thoroughly than any writer before him, especially in the matter that salvation comes through justification by faith. It is a central and repeated theological axiom that Hilary discusses throughout the commentary…

It’s very interesting that our first Latin Matthew commentary is so saturated with Paul’s theology.

There was a wave of interest in Paul’s epistles in Latin theology in the late 300’s, a “generation of St. Paul” with a “focus on Pauline themes and implications” that “would significantly change the direction of Latin theology.” The most famous result of this is the anti-Pelagian work of Augustine starting the 390’s, but there was an extensive development leading up to that: Marius Victorinus commented on Galatians, Ephesians, and Titus; the anonymous scholar we call Ambrosiaster commented on all the Pauline epistles; and dubious characters like Tyconius, Donatus, and Priscillian were also at work on Paul in this period.

Why did everybody in the West start reading and arguing about Paul in the fourth century? In his article, Williams reports that some historians think this wave of Paul studies might actually have been prompted by Hilary’s Matthew commentary! Williams follows up on this conjecture by reviewing the way Hilary, sixty years before Augustine, finds himself paraphrasing the theology of Matthew by using terms like “justification by faith” (fides iustificat, or fidei iustificatio), terms which Latin theologians weren’t even explicitly using in their discussions of Paul yet. Williams says

It is historically noteworthy perhaps to observe that Hilary is the first Christian theologian to have formulated explicitly what Paul left implicit by referring to God’s work of grace in the phrase fides sola justificat: ‘”because faith alone justifies… publicans and prostitutes will be first in the kingdom of heaven.” In effect, those who are neediest are the ones most likely to accept the free gift of salvation.

Hilary also “comes as close as any early writer before Augustine to formulating the term “original sin.”

Williams draws a number of conclusions from his work on justification by faith in Hilary’s commentary on Matthew. One that is interesting to me is the way the church fathers read different parts of the Bible together, because of their commitment to the whole volume being God’s word. The majority of Christian interpreters in the fourth century “did not use Pauline theology as the grand template by which all other scriptural testimonies must be evaluated,” he notes.

Even with the revival of of Pauline studies, the process that guided biblical hermeneutics remained gospel, apostle, and prophet. The ancients did not atomize the biblical text into watertight compartments –a method that still characterizes much of modern biblical scholarship. It had been discovered already by the second century that an overemphasis on one text or another, or ignoring the Old Testament in the face of the New Testament narrative, led to the hermeneutical impoverishment of all.

Another way to say that is: “from a patristic standpoint, therefore, it is not at all odd that we should find Pauline ‘school’ interpretation in a commentary on Matthew, just as it was necessary to have Matthew to understand the Old Testament and vice versa.”

Whatever weaknesses patristic Bible interpretation may have (I avert my eyes from those weaknesses for the moment), it had an obvious strength in its ability to grasp the entire meaning of the Bible as a unified whole. As Williams notes, “it was typical of the patristic mind to regard the Bible as possessing an inner coherence, and to argue that gospel, apostle, and prophet bore complementary witness to the ordo of one God. In practice, this meant that one part of the Bible helps readers understand other parts, and by this process will the reader be able to understand properly any one part.”

And one last implication of the theology of salvation in Hilary’s Matthew commentary, worth noting for Protestants especially, comes in Williams’ excellent concluding paragraph:

There can be no question that a strong platform of solus Christus underlies the early church’s soteriology. Christ alone was “true God of true God” and was able to fulfill the divine plan of re-creating the fallen creation. It was almost universally accepted that the work of salvation is completely God’s work on our behalf and that without God’s initiative toward us in Christ, Adam’s race has no hope. Whatever good the human will might achieve, it is not enough for humanity’s redemption though it may spur the diseased will by its own needs to God. It is God’s justification of the sinner, graciously accomplished through the cross of Christ and by the grace of the Holy Spirit, that enables restoration of the divine image. Undoubtedly, this was Hilary’s purpose when he established the vocabulary of fides sola iustificat. By the time of the sixteenth-century Reformation, such language was hardly new.