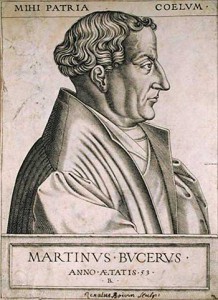

Today (November 11) is the birthday of Martin Bucer (1491-1551). An important Reformer, he did his work in a no-man’s land between what would become the stable confessions and denominations of later decades. This is one of the reasons he is not frequently remembered. Though he influenced the Lutherans, the Reformed, and the Anglicans, he belongs to none of them.

Today (November 11) is the birthday of Martin Bucer (1491-1551). An important Reformer, he did his work in a no-man’s land between what would become the stable confessions and denominations of later decades. This is one of the reasons he is not frequently remembered. Though he influenced the Lutherans, the Reformed, and the Anglicans, he belongs to none of them.

Trained as a Dominican, he heard Luther’s arguments, was persuaded, and arranged to be released from his monastic vows. Later he was expelled from the Roman Catholic church as his reforming efforts became more clearly unaligned with the Roman positions. As a Protestant, he labored mightily to reconcile the Lutherans and the Zwinglians on the question of the Lord’s Supper, convinced that they were saying the same thing but using different terms. He commended a careful vagueness about the way Christ was present in the Lord’s Supper, blurring as many distinctions as possible, and quoting copiously from the Bible and the church fathers, without undue interpretation or specificity. As a German, he tried to help emperor Charles V assemble a German church that included Lutheran and Catholic believers in the territories of Germany, distinct from Rome. It would have been a sort of German version of the Anglican experiment. In retrospect it’s easy to pronounce the idea foredoomed, but it could have altered the course of European history by redrawing the political lines before the wars of religion heated up.

In 1549 he found himself with no homeland on the continent, and accepted an invitation to come to England as a senior consultant on All Things Protestant. He was given the Regius Chair of Divinity at Cambridge, was asked to advise on the revisions to the Book of Common Prayer, and continued his ministry of teaching, scholarship, and pastoring. He was never comfortable in England, and by most accounts the Cambridge climate (and bad British wine) undermined his health. During Mary’s reign, his dead body was considered symbolic enough of Protestantism Itself that it was dug up and desecrated.

He spent most of his life being accused of being too compromising, but he was driven abroad because he was too unyielding. He was a creative thinker who tried to frame solutions to intractable problems of his age. After his death, nearly every kind of Protestant would claim him: The Lutherans and the Zwinglians alike, the Anglican churchmen and the Puritans, all manner of Reformed churches would claim him, and even the Remonstrants would point to him as a less dogmatic kind of Calvinist.

There is not now, nor has there ever been, much Bucer available in English, and the reviews of his Latin works emphasize how prolix and convoluted his writing style was.