.

But as for you, continue in what you have learned and have firmly believed, knowing from whom you learned it and how from childhood you have been acquainted with the sacred writings, which are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.

–2 Timothy 3:14-15

The first book you ever read was a book you didn’t read, but one that was read to you.

And whatever “first” might mean, it’s safe to guess it wasn’t read to you once, but repeatedly, over and over and over again.

By the time you came to your senses and grew into the awareness that you were hearing Goodnight Moon or Good Dog, Carl, the good words of those good books had been sounding over your crib or cradle for a good long time.

You were immersed, O reader, in the amniotic fluid of signs and symbols; surrounded by alphabet soup; always already swimming in a sea of language before you started chirping a few little bits of it back and taking your place in the community of communicators. From childhood you have known writings.

Open your eyes, take a deep breath, cut the umbilical cord (and here, towel off, you’re a mess) and join the great reading party as it mounts another raid on the fortress of that which has been written before we got here.

Welcome to our reading life.

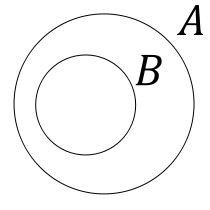

Reading? Life? But surely, you object, life is more than reading? Surely reading is at best an indoor sport, a retreat, something that takes us away from the rush and the rhythm of reality itself, from the vast course of human events and the pulsing, wordless reality of the whole physical world. Surely reading is a break from life, an alternative to life, an oasis in the midst of life. Surely on the great, cosmic Venn diagram of the absolute, the circle marked “all that is” is a much larger circle than the circle inside of it labeled, “all that is written.”

Reading? Life? But surely, you object, life is more than reading? Surely reading is at best an indoor sport, a retreat, something that takes us away from the rush and the rhythm of reality itself, from the vast course of human events and the pulsing, wordless reality of the whole physical world. Surely reading is a break from life, an alternative to life, an oasis in the midst of life. Surely on the great, cosmic Venn diagram of the absolute, the circle marked “all that is” is a much larger circle than the circle inside of it labeled, “all that is written.”

That is undeniably true. Before you can be a reader, you have to be. We can add that statement to the even smaller circle labeled, “terrible T-shirt slogans that sound deep but aren’t.”

Still, it’s a fact: a decent respect to the opinions of mankind impels us to justify in advance any words we speak in praise of reading, so that what we say about reading is something added to, rather than subtracted from or played off against, our praise of all blessings, and of God from whom all blessings flow.

Surrounded by life, the universe, and everything, by what warrant do we bury our noses in books? Here is the warrant, the same warrant that justifies art of any kind.

Forget for a moment the first book you ever read. That’s too hard a question anyway, and it raises the Socratic question “what is reading, my friend” which would take us too far afield (“Is it a craft like others, say, shoemaking?”) For some of you it’s untraceable in your early consciousness. For some of you it was Homer’s Iliad and it happened last week.

Instead, think about the first beauty you ever experienced.

What was the first beautiful thing that ever caught your eye and turned your head? I sometimes ask this in class, and over the years I’ve heard wonderful answers: trees and clouds and sunsets, of course, or views of the ocean. But also Christmas trees and special clothes. Sometimes Mom or Dad dressed special for something. Sometimes food, especially party food.

And when college students search their memories long enough to find the shelf where they keep the truth about this, they very often have answers that now embarrass them. Disney princesses and doll houses. Lots and lots of toys, some of them well made: that tiny tank engine with a tiny face incongruously applied to it, that fits right there in your tiny hand: Thomas (he’s the cheeky one).

But some of them are not made well at all; some gaudy cheap plastic monstrosity that your parents wish you hadn’t fixated on, but towards which you feel a loyalty and admiration verging on the religious. They would have thrown it away if you had ever put it down or let it out of your sight, but you wouldn’t, because here was Beauty. And many students have to confess that the first time they saw something beautiful was on a TV show that they now know better than to ever watch again, lest the reality disappoint too bitterly.

But there’s some sleight of hand happening here. When I ask, “what was the first beauty you ever experienced,” rather than “what was the first beautiful thing that ever presented itself to you,” I’m presupposing that you were conscious and aware of what you were seeing, and I’m really asking, and you are really answering, that question: What was the first beauty that succeeded in arresting your attention, and thereby lodging itself in the storehouse of your memory?

Because time and memory would fail us if we tried to declare the first beauty we ever saw. It would coincide perfectly with the first sight we ever had, because we come into this world as into a treasure house of beauties, surrounded on all sides by loveliness and marvels, by highly improbable configurations of things that harmonize and contrast and play off of each other in objectively wonderful ways.

Our first exposure to beauty is our first exposure to this world; it is so immediate that it predates our birth and surrounds us in the womb. You all look so mature, but you’re a bunch of grown-up embryos that once floated in a tiny room of warmth and soft textures and muted sounds and dimmed lights, taking in only what you could bear, and grasping even less of it.

Our first exposure to beauty is our first exposure to this world; it is so immediate that it predates our birth and surrounds us in the womb. You all look so mature, but you’re a bunch of grown-up embryos that once floated in a tiny room of warmth and soft textures and muted sounds and dimmed lights, taking in only what you could bear, and grasping even less of it.

Our lives as full-grown former fetuses are not much different: mostly unaware, we are suspended in beauty that gets to us through filters and balances and careful arrangements that enable us to see a little and understand less.

Surrounded by so much beauty, why is our first awareness of it so often –I almost said usually, and I’m tempted to say always— an experience of beauty in an artifact created by another human? Why is our first knowing of beauty a knowing it in a crafty microcosm?

C.S. Lewis, who thought very hard and wrote very well about this, tells the same tale. He reports that his first pang of joy came to him in the memory of the time his older brother came to him in the childrens’ room and showed him a little thing he had made: It was a biscuit tin filled with moss. It was a little metal container stuffed with green moss, maybe a few twigs to be trees, and it represented a beautiful landscape. But try to picture this: young C.S. Lewis was being raised in a northern country of beautiful landscapes. He could have looked out the window and seen a real garden, with real hills piled up and stretching beyond it to a northern sky. Why did the tiny simulacrum pierce his soul? No disrespect intended to his older brother Warnie, but this hand-held toy garden probably wasn’t even very well made. But Lewis saw it and knew it. It found him; it reached him.

C.S. Lewis, who thought very hard and wrote very well about this, tells the same tale. He reports that his first pang of joy came to him in the memory of the time his older brother came to him in the childrens’ room and showed him a little thing he had made: It was a biscuit tin filled with moss. It was a little metal container stuffed with green moss, maybe a few twigs to be trees, and it represented a beautiful landscape. But try to picture this: young C.S. Lewis was being raised in a northern country of beautiful landscapes. He could have looked out the window and seen a real garden, with real hills piled up and stretching beyond it to a northern sky. Why did the tiny simulacrum pierce his soul? No disrespect intended to his older brother Warnie, but this hand-held toy garden probably wasn’t even very well made. But Lewis saw it and knew it. It found him; it reached him.

Why? Because it was art, and it echoed reality itself while fitting in his hand. He turned his head away from the beauty of Ireland, which he wasn’t paying attention to anyway, and focused his mental and perceptual abilities, powerful but immature as they were, on that shabby little tin full of moss in the hand of his brother. That artifact gave him Ireland: not gave it back, but gave it for the first time, gave it to somebody who now had eyes to see.

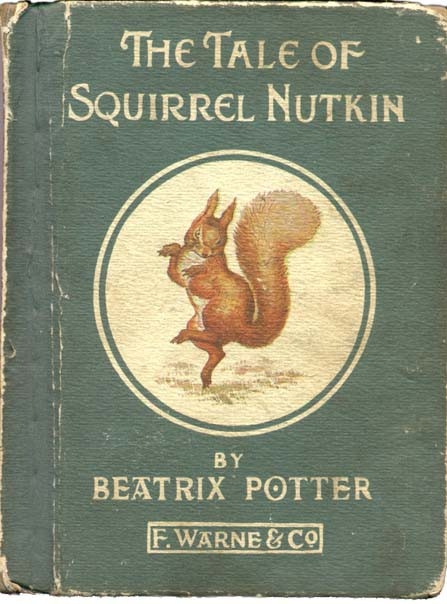

The second stab of joy that CS Lewis remembers, by the way, was The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin by Beatrix Potter. “It troubled me,” he said, “with what I can only describe as the idea of Autumn.” Who knows why? It was a book, a little book, something crafted by a superior senior intellect that could fit in your hand. From childhood he knew those writings.

The second stab of joy that CS Lewis remembers, by the way, was The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin by Beatrix Potter. “It troubled me,” he said, “with what I can only describe as the idea of Autumn.” Who knows why? It was a book, a little book, something crafted by a superior senior intellect that could fit in your hand. From childhood he knew those writings.

So our reading life is reading for life; reading as the experience of the literary art which focuses and localizes a reality that is apparently too grand and overwhelming for us to give our full attention to with such immediacy. Reading great books is a chance to face reality through the prism of carefully crafted objects of art tested by time and worthy of our attention. We don’t bring fully formed faculties to the task; we open our still-forming eyes and ears to things we hadn’t previously known in their wild form. We learn reality by joining the human community that is already talking about it. From childhood we have known these writings.

So in our reading life, we ought not to oppose reading to life, or life to reading. In Christian circles, mark the person who continually shouts out, “Christianity is more than a doctrine, it’s a life!” More often than not, that’s the person who’s lost the plot. Reading is for life.

And reading books, done right, is itself practice in reading all things. Practice with the nouns on the page prepares us for the nouns all around: all the persons, places, and things.

We read persons: What do they mean by what they say and do? How do you interpret them correctly? How do you keep yourself from over-interpreting them or under-interpreting them? It’s difficult and dangerous, so we practice on dead people. Plato’s not insulted if you read him wrong; he’s in the Phaedrus (oddly, a book he wrote about how writing books was bad) waiting for you come back and get him right. Your roommate, on the other hand, is immediately offended to be read wrong, and says so.

We read places: Where are you and what place did you come from? What is this place? What are the names of these trees and these streets? We all just got here, we’re all just grown up fetuses, and we’re all trying to figure this out and talk to each other about it.

And we read things: all things, visible and invisible, as the creed says. God made the things we see and God made invisible createds, things we don’t see. Want to see one? Too bad. But God made them, and we learn to read them by reading the visible signs.

But we are speaking metaphorically, and by “we” I mean “I,” because I have the microphone. So he said to himself, “Self,” I said, “let’s be careful here. Books are books, but other nouns are other nouns. Not everything is a book.”

True. So I close with the most important thing about our reading life. From childhood you have been acquainted with the sacred writings, the holy scriptures, which are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.

God has authored a book, and it is a very large and very strange book, which very young people can understand in a way appropriate to them, but which the very old and the very wise can never outgrow, and should never assume they have attained mastery of. In that book, which most of us have long known in a dim and often uncomprehending and inattentive way, he has revealed his character, because in that book God the Father has made himself known in the sending of his Son and the giving of his Spirit. The character called God in that book called the Bible has a particular identity which he has himself made known. It is a kind of autobiography, though surely it’s the strangest one on record.

We are also, each of us, living out the raw material for an autobiography, and here the ambiguity returns. Our lives are not literally books; not even literally stories. They are lives. Yet we are often tempted to read them as books, as stories in which the character of God is disclosed, revealed, made known, and established.

But our lives are not God’s autobiography; he already wrote one. In that peculiar book, we learn from him who he is, what he is like, what he has promised, what we can count on him for.

In the course of our lives, we see all kinds of things happen. If we pay close attention to ups and downs of our lives, tracing and recording the rising and falling and twisting and turning of our ways, we can learn to discern God at work in the many things that happen to us. We can see God at work, if we already know God’s character. If we know what to look for, we can spot his handiwork.

That is, we can re-cognize the presence of God in the course of our lives, but only if we have already cognized him elsewhere. When, in the course of your life, you can’t see God’s hand, you can still trust his heart. But where can you come to know God’s heart, in order to trust it when his hand is hidden shadow?

From childhood you have known. God acts in history in accordance with his revealed character. He acts in world history in accordance with his character; and he acts in your personal history in accordance with his character. In how much accordance? It must not be total, or at least it must not be conspicuous, or we wouldn’t speak of the role of faith in perceiving the invisible ways of God with us: they would be visible. God’s presence in our lives must be not the presence of self-evident, visible, tangible, sensible presence, but enough for faith. So we say “God moves in a mysterious way,” and we think of the mysterious way he moved in the course of events that make up the life of the patriarch Joseph.

We read about Joseph in Genesis, Bible stories we have known since we were children. But imagine if Joseph took the events of his own life as the primary text that made God known to him. Who is God, according to the course of Joseph’s life? A God of slavery, betrayal, fratricide, dislocation, exile, false accusation, imprisonment, long years of apparent neglect, and so on. But as bad as Joseph’s situation was at times, he was never in the most terrible situation, that of having to guess at God’s identity from the mere facts of his life. He knew the truth of the character and faithfulness of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That God moved in very mysterious ways in Joseph’s life, and Joseph could read his ways because he brought the wisdom with him, from the God of his fathers, from the sure word that God had spoken to Abraham.

William Cowper, who wrote the hymn “God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform,” gestured towards the cosmic and impersonal way God rumbles behind the scenes: “He plants His footsteps in the sea and rides upon the storm.”

But he went on to give advice about how to read God’s ways in our lives:

Judge not the Lord by feeble sense,

But trust Him for His grace;

Behind a frowning providence

He hides a smiling face.Blind unbelief is sure to err

And scan His work in vain;

God is His own interpreter,

And He will make it plain.

“God is His own interpreter,” and in the writings we have known since childhood, he has made plain his character and his identity; on that basis he will make it plain again. His book is text indeed, and your life is commentary. To get the right meaning from the derivative text as you make your way through it, you need to arrive with an already formed acquaintance with the central character.

So welcome to our reading life, our life of reading, our reading of life. Life is more than reading. Therefore we read; we read as if our lives depended on it. Read for your life.

Father God, we have set before us the task of reading together as an academic community that is also a community of believers in your word. In our work together, will you undertake to be our tutor, and for your wisdom to take and to retain the form of a mentor? As we examine your word, will you examine us by your word? As we open your book, will you open your own most holy lips and speak to us? As we read line by line will you lead us step by step? As we turn these pages, will you turn our hearts to you, the foundation and fountain of all being and beauty? Will you show us marvelous things in your law, things that form our half-formed selves and souls into the likeness of your beloved Son, in whose name we pray, Amen.