I was invited to contribute to a Banned Book Colloquium in Biola’s library on September 25, 2006. I presented the following brief paper on the most important banned book in Biola’s history.

In 1927, the second Dean of the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, John Murdoch MacInnis, wrote a book called Peter the Fisherman Philosopher: A Study in the Higher Fundamentalism, published by Biola Book Room. The alarmed reaction to this book ignited a controversy that led to MacInnis’ resignation, the recall and destruction of the book, and the banning of the book from the Bible Institute’s library collection. What was in that book, and what was at stake in this controversy?

The best book on the controversy over Peter the Fisherman Philosopher, in fact the only fully-documented scholarly investigation, is a dissertation by Daniel W. Draney, filed at Fuller Theological Seminary in 1996, entitled “John Murdoch MacInnis and the Crisis of Authority in American Protestant Fundamentalism, 1925-1929.” My presentation today is dependent on Draney’s careful historical work, though some of the analysis is my own —in fact I am sure my interpretation of things runs counter to Draney’s at several points. But he’s the professional historian, and only because he did his work so well can I piece together a different interpretation. Draney noted that “few are likely to read a dissertation of this sort” (Draney, iii), but I read his dissertation and am reporting to you on the bare historical outline of the controversy.*

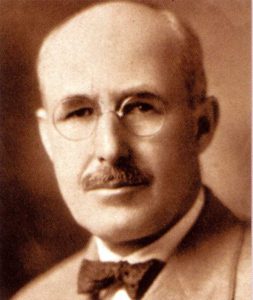

The author of Peter the Fisherman Philosopher: A Study in the Higher Fundamentalism was John Murdoch MacInnis (1871-1940) was the second dean of the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, and resigned in 1928. He was born in a tight-knit Scottish highlander community on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Largely self-educated, he had done about one year of course work at Moody Bible Institute and then gathered a series of correspondence degrees and an MDiv. MacInnis became dean after the resignation of R. A. Torrey in 1924.

MacInnis had written the bulk of the book several years before coming to Biola, and had delivered most of it in public lectures already. On October 11, 1927, the Bible Institute of Los Angeles board of directors agreed to publish this book by their new dean, printing two thousand copies via their own publishing arm, the Biola Book Room. By December, the book was printed and was being advertised for sale in the King’s Business, Biola’s monthly periodical. It was a small book, less than two hundred pages, with large type and wide margins.

The next month, January 1928, a Biola employee named Marion Reynolds, a 1917 graduate of the Institute, began criticizing the book. His main charge can be summarized as: Dean MacInnis is a modernist, a liberal who has betrayed the founders of Biola and is turning the Institute into yet another modernist school. On January 6, the board of directors asked Reynolds and T. C. Horton to stop what the board viewed as a negative campaign against MacInnis and his book. Horton quieted down, but Reynolds got louder. By January 16 he had printed and distributed a 62-page critique of the book. The critique is a rambling and disjointed attack on Peter the Fisherman Philosopher. Reynolds accuses MacInnis of denying biblical inerrancy, the deity of Christ, divine revelation, and the atonement. Plus MacInnis was guilty of frequent quotations from secular philosophers, modernists, and atheists, and smokers. (This is not a cheap shot: “Let us be done with tobacco smokers!” actually appears on the final page of the Reynolds critique.) The board of directors promptly terminated Reynolds’ employment on grounds of insubordination.

Reynolds’ firing mobilized a group of agitators loyal to him to begin asking hard questions, and events in “the MacInnis affair” developed rapidly from this point on. Reynolds himself approached the Biola Alumni Association and asked them to form an investigative committee. Three days later the board called for a vote of confidence in MacInnis, at which only six students stood up in opposition to him. A Biola employee named W. A. Hillis resigned in protest, and began networking among people who were financial supporters of the Bible Institute, encouraging them to liquidate the annuities which they had given to Biola. The board responded to this financial attack by threatening a lawsuit against Hillis.

In Feb 6, 1928, MacInnis took the step of submitting his resignation to the board, and the board expressed their support of MacInnis by refusing to accept the resignation. As soon as Biola thus affirmed its Dean, eleven conservative magazines attacked the book and, more importantly, attacked Biola for supporting it.

The Bible Institute formed an interdenominational committee to study the book, made up of Los Angeles area pastors who were for the most part trusted by fundamentalists. This committee declared the book to be free of heresy. The fundamentalist press, in Los Angeles and beyond, felt betrayed by the committee’s findings, and by the Bible Institute’s continuing support of its dean. Over that summer they used a variety of methods to put pressure on the school.

On Nov.13, MacInnis resigned again, the board accepted his resignation, and the following week four board members resigned in protest. In fact, in the next few months as many as twenty teachers or employees resigned from Biola, including G. Campbell Morgan and Alva McClain. Half of the Bible faculty resigned.

On December 7, the board issued a statement defending both MacInnis and their decision to accept his resignation. MacInnis was good, terminating him was good. Everyone was confused. On December 28, they issued a clarifying statement: MacInnis had not departed at all from the fundamental truths of Biola’s statement of doctrine, and was not a modernist. But he had attempted to take Biola in “a direction more scholastic than spiritual.” This statement pleased nobody: not MacInnis, not the moderate denominations, and not the militant fundamentalists. Nor did it mention Peter the Fisherman Philosopher, as the fundamentalist critics of course pointed out.

On Jan 21, 1929, the board repudiated the book, and discontinued its sale and circulation, stating that it did not represent the position of Biola. Critics pointed out that this new statement contradicted earlier statements, so one week later they issued another statement that did not explicitly condemn Peter the Fisherman Philosopher.

The mixed messages obviously had to stop, and on March 20, Charles Fuller presided over a board meeting which made the following declaration, which was published in the April issue of the King’s Business:

The mixed messages obviously had to stop, and on March 20, Charles Fuller presided over a board meeting which made the following declaration, which was published in the April issue of the King’s Business:

Because we recognized that we were in error in commending the book Peter, the Fisherman Philosopher, the Board some time ago accepted the resignation of the author, and he has now absolutely no connection with the Institute; and being determined that our testimony to and teaching of the Fundamental doctrines of Christianity as set forth in the Institute’s Statement of Doctrine shall be so clear as to be absolutely above all possibility of suspicion, we hereby express our disapproval of said book, and declare that its thought and teaching does not represent the thinking and teaching of the Bible Institute today; and further, as a first step in the execution of our determination to pursue a course which will put this Institute’s loyalty to the Bible beyond question, we have already discontinued the use, sale, and circulation of the book Peter, the Fisherman Philosopher in the Bible Institute or elsewhere, and all remaining copies, together with the type-forms, have been destroyed.

(For a version of this story that features Charles Fuller as the hero, read chapter 5 of Fuller’s biography).

This at last was a dramatic act of symbolic repudiation, and while it pleased the critical fundamentalist press, it also overshot that audience by a wide margin, and drew the attention of the national secular press. The Los Angeles Times declared: “Bible Leaders Destroy Book,” and the Syracuse Post-Standard made the dubious historical claim, “Dr. MacInnis’ Book First Destroyed in Modern Times.” It was probably this controversy rather than the content of the book that led Harper to reprint it in 1930.

When MacInnis left Biola, he consciously left behind the whole extra-denominational parachurch fundamentalist movement. He re-entered mainline Presbyterian history as a regional educational administrator of the mostly conservative type. MacInnis’ sense of ministerial vocation had always been defined by his denominational commitment, which seemed to run in his Scottish blood. Biola’s other early leaders were comfortable in many denominations —Torrey described himself as an Episcobaptipresbygationalist— but MacInnis was ethnically Presbyterian. His only other book was the 1936 volume published by Westminster Press, The Church as Teacher. His extensive collection of letters and papers are on file in the Presbyterian Church USA historical archive in Philadelphia.

What exactly was in that book? First of all, it is important to note that it was a bad book. MacInnis was mainly self-educated, was not in the habit of submitting to a regular course of instruction, and had a lifelong habit of reading widely in subjects beyond his grasp. In fact, this is the most telling way I can frame a criticism of his intellectual style: his reach exceeded his grasp, so he was constantly fumbling his fingertips against big ideas. His prose style ranges between a serviceable literary preaching voice when he is at his best, and at his worst a mind-numbing combination of bureaucratic cant with incantatory vision-casting. It is a thing easier to illustrate than to describe:

The Higher Fundamentalism is that insight of a living experience which is the light of life. It does not ignore or set aside doctrine. On the contrary, it grows out of a sound doctrine, making possible true insights which provide a genuine and adequate philosophy of life. An adequate philosophy or interpretation of life is the explanation that most satisfactorily solves the problems which life itself presents and makes possible the truest and highest kind of living. (page 15)

Where does the Higher Fundamentalism come from? We learn it from Peter:

But it is clear that Peter had an experience in which he related himself to God so as to make it possible for God to show him what he could not find in the ordinary ways of thinking represented by the phrase “Flesh and blood.” Let me state this philosophically. Peter related himself to the final source of stimulus in such a way as to make it possible for him to be stimulated to thoughts that he could not think apart from that special stimulus. That means that Peter had a special experience of reality t hat made possible this exceptional insight. Jesus calls the final source of stimulus “My Father who is in heaven.” (page 18)

And:

Jesus recognized the genuineness of Peter’s experience of God and immediately declared that on such an experience He could build His church and make it effective. Not on Peter, nor on Peter’s confession, but on that experience of God which interpreted the life and thought of God. The church is the body raised up by Christ to reflect and interpret God in the world “to understand and live the life that He was living, therefore, it can not be built on tradition or on mere ritual. It must have as its rock foundation an immediate and constant experience of God. It is only necessary to review history in the most general way to see how wonderfully this fact is illustrated by it. p. 20

MacInnis’ entire schtick is to take a statement by Peter, emphasize how homespun and rustic this simple day laborer was, and then to conceptually paraphrase Peter’s simple statements into high-flying modern philosophical categories. After thus emphasizing the low origins and the high aspirations, MacInnis would then state his overriding thesis: this simple fisherman was able to say things that the best of modern thought is just now catching up with. MacInnis was attempting a kind of cultural-intellectual apologetic to a post-World War I audience worried about the foundations of civilization. The book had mainly been written in the years after World War I, and the fact that it was not published until the late 1920s reduced its already slim chances of communicating with its intended audience even further.

MacInnis’ pedantic tone is easy to satirize, as can be seen in this (apparently unpublished) anonymous spoof called “Brer Jackson Elucidates the Inwardness of Peter the Fisherman Philsopher” from 1928:

Simon Peter experienced an insight into an interpretation. An insight into an interpretation Simon Peter experienced. If Simon Peter experienced the interpretation into the insight, what was the insight of the experience that Simon Peter interpreted?

Draney’s 1996 dissertation on the controversy convincingly argues that John Murdoch MacInnis had a reformist vision for American fundamentalism. He hoped to move the Bible Institute back to the sunny 19th-century evangelical spirit of Dwight L. Moody, and hired as many Moody-influenced faculty members as he could. He was trying to staff the Bible Institute with men who had been a part of the evangelical revival before the harsh weather of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy had moved in. His paradigmatic hire in this regard was G. Campbell Morgan. To carry out this reformist agenda, MacInnis would have to split off the radical and militant fundamentalism who were all too willing to purify themselves into smaller and smaller groups. And finally, MacInnis intended to reconnect the main body of the fundamentalist movement to the Protestant denominational mainline.

Draney’s 1996 dissertation on the controversy convincingly argues that John Murdoch MacInnis had a reformist vision for American fundamentalism. He hoped to move the Bible Institute back to the sunny 19th-century evangelical spirit of Dwight L. Moody, and hired as many Moody-influenced faculty members as he could. He was trying to staff the Bible Institute with men who had been a part of the evangelical revival before the harsh weather of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy had moved in. His paradigmatic hire in this regard was G. Campbell Morgan. To carry out this reformist agenda, MacInnis would have to split off the radical and militant fundamentalism who were all too willing to purify themselves into smaller and smaller groups. And finally, MacInnis intended to reconnect the main body of the fundamentalist movement to the Protestant denominational mainline.

Described in this way, the MacInnis plan was truly visionary, and something that needed to be done. R. A. Torrey probably could have done it: Torrey had protected the Bible Institute’s right flank during the contentious years of early fundamentalism. Lyman Stewart had hired Torrey in 1912 with the specific mandate for Torrey to squash a sectarian hyper-dispensationalist uprising among the Bible Institute faculty and staff.

MacInnis, however, was no R. A. Torrey, and no doubt he grew tired of hearing this comparison as he struggled to fill the Deanship which Torrey had created. He was neither a world-traveling evangelist nor a Yale-educated intellectual. He certainly did not have the conservative credibility demanded by an increasingly jittery fundamentalist right. And above all, it was his inadequate reading of the spirit of the age that foredoomed the MacInnis program to failure.

MacInnis’ overall strategy for Biola was to undertake the experiment of pursuing a new and different constituency. This is a dangerous operation even in stable conditions with administrative continuity, but for a new administration to attempt it in a time of seismic social shifts was institutional suicide. MacInnis’ tactical decision, most clearly on display in writing and publishing Peter the Fisherman Philosopher, was ventriloquistic: He was trying to throw his voice out of the Bible Institute community to catch the ear of the broader world of conservatives in the mainline denominations. Perhaps there was somebody who could have spoken to that constituency, but they would have to have been far more insightful regarding the temper of the times, the complex overlapping layers of fundamentalism as it repositioned itself over against entrenching modernism in the denominations, and the overall drift of American culture between the wars. They would have to have had a birds-eye view of intellectual developments and a solid grasp of the actual fundamentals. They would have to have been so well grounded theologically that they could make use of modern thought without being used by it and having their own goals co-opted by the modernist spirit of the age. They would have to know the workings of the mainline denominations well enough to stay connected without compromising, and leverage Biola’s relative institutional independence toward maximal impact on the denominations. And as they tried to speak to a broader constituency, they would have to have been able to maintain and even deepen the trust of their actual consistency. Lightly equipped and ill-informed as he was, MacInnis made the classic mistake: he ended up speaking to an imaginary constituency while ignoring Biola’s actual constituency. Ultimately he found himself speaking to nobody and irritating everybody.

If someone more qualified than MacInnis had been in charge, the MacInnis program itself (marginalizing radical fundamentalists, reviving the Moody spirit, and engaging the mainline denominations) could have been carried out. MacInnis was not the right leader for his own project, and his spectacular failure spoiled Biola’s chances of being the institution which could have kept the fundamentalism of The Fundamentals from degenerating into the fundamentalism of the ’30s. The transitional years after the retiring of the founders would have been difficult for anybody to navigate, and the Great Depression was just about to blindside the entire institution. A leadership implosion and a dramatic book-banning only made matters worse and severely compromised Biola’s mission.

If someone more qualified than MacInnis had been in charge, the MacInnis program itself (marginalizing radical fundamentalists, reviving the Moody spirit, and engaging the mainline denominations) could have been carried out. MacInnis was not the right leader for his own project, and his spectacular failure spoiled Biola’s chances of being the institution which could have kept the fundamentalism of The Fundamentals from degenerating into the fundamentalism of the ’30s. The transitional years after the retiring of the founders would have been difficult for anybody to navigate, and the Great Depression was just about to blindside the entire institution. A leadership implosion and a dramatic book-banning only made matters worse and severely compromised Biola’s mission.

Biola’s suppression of Peter the Fisherman Philosopher was not an issue of free speech, but a question of advocacy: did this book by the dean, published by the Biola Book Room, represent the position of the Bible Institute of Los Angeles? It was a confusing book met by a confusing response. The big question throughout the controversy was: What does Biola stand for? That was all anybody wanted to know, and that was precisely what the leadership could not articulate during this critical transition.

*Update: Draney subsequently published a book based on his dissertation: When Streams Diverge.