It’s not exactly a comic book, but there is an old catechism that certainly makes an interesting use of sequential images for the purposes of teaching Christian doctrine. The Huntington Free Library in the Bronx published a facsimile edition of a “pictographic Quechua catechism” that is a wonderful and engaging little booklet. Here is the page that corresponds to the Apostles’ Creed:

You do have to stare pretty hard at these little stick figures (click through for enlargement), but admit it: they’re charming. Here’s a little explanation of the first line of the first page, as provided by the facsimile edition (ed. Barbara Haye and William Mitchell).

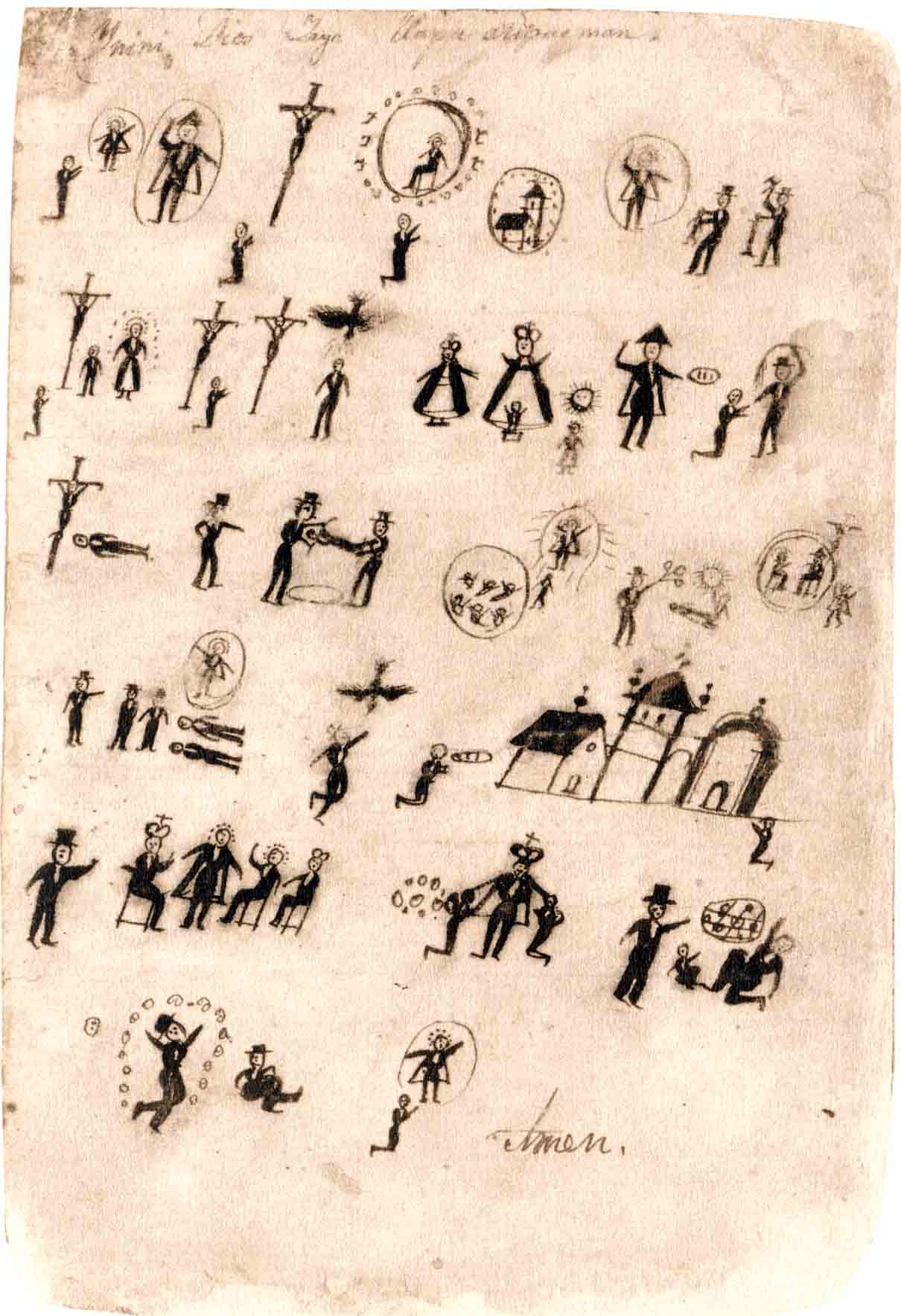

Kneeling figure on the left means “I believe.” This figure gets repeated several times throughout the creed. Here in the first article of the creed, what he believes in is God the Father, who is depicted first as God, a figure in an oval, and then as Father, a figure in an oval dressed like your dad if your dad wore a cape. Notice that this book must be a memory aid more than a written record: You already have to know the creed in order to benefit from this pictorial version of it very much.

Kneeling figure on the left means “I believe.” This figure gets repeated several times throughout the creed. Here in the first article of the creed, what he believes in is God the Father, who is depicted first as God, a figure in an oval, and then as Father, a figure in an oval dressed like your dad if your dad wore a cape. Notice that this book must be a memory aid more than a written record: You already have to know the creed in order to benefit from this pictorial version of it very much.

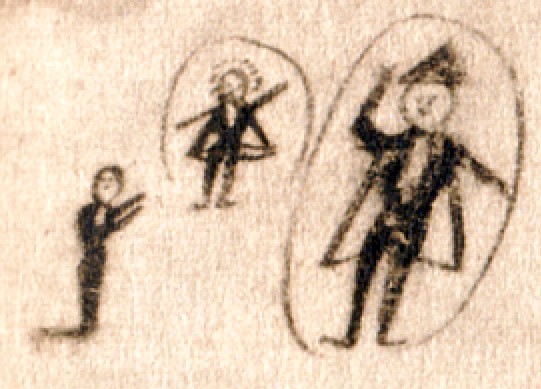

The next image is the kneeling man again, but now in front of a crucifix. It seems to me this is out of place here, since the Son of God is not introduced until the second article. Perhaps it simply indicates the Christian character of this profession of faith? The rest of the top line seems to devote considerable effort to spelling out the title of the first person of the Trinity, “God almighty, maker of heaven and earth.”

“I believe in heaven and earth” is the phrase suggested by the commentators, and that certainly would follow the order here of kneeling man in front of two symbolic circles. The first one is described as “ornamented circle with seated God,” which seems about right. The second circle is a circle whose ornaments are inside itself, along with a church building. Heaven and earth are obviously being shown, but I think they correspond to “maker of heaven and earth” rather than to “believing in heaven and earth.”

The last image on the line repeats the God cipher (standing man in oval making gesture of authority), but then adds two little humans: One holds out a piece of wood (?) and is raising an axe over it. The second is holding out a little human figure. The commentators offer this possibility: The concept of Father is shown by the “man holding child or soul,” and the concept of Maker is shown by the man holding a tool to shape something. I think that’s probably right, but I can’t help thinking of Athanasius’ remark that “a man by craft builds a house or statue, but by nature begets a son.” Is the ambiguity in this image a weakness or a strength of the catechism’s pictographic approach?

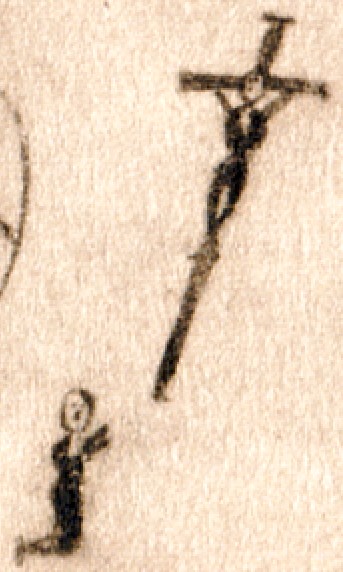

At the bottom of the first full page is a lovely image that the modern editors cleverly chose to put on the front of their book. It seems to correspond to “I believe in life everlasting,” and is described as “dancing man in bubbly circle with another man resting at right.” Behold:

Is heaven a state of active joy or of perfect rest? Somehow it must be the non-contradictory unity of what is best in both. So why choose: draw the bubbly-dancing man and also the (well dressed!) resting man.

Who knows how the missionaries and priests explained these drawings to the locals? The main attraction for them was no doubt simplicity and clarity, with an emphasis on these stylish stick figures as memory aids. But as I study these pictures I often find not clarity but ambiguity, polysemy, and a rich suggestiveness that could never have been accomplished in such tight spaces if the medium had been words rather than minimalist pictures.